Achieving consistency

advertisement

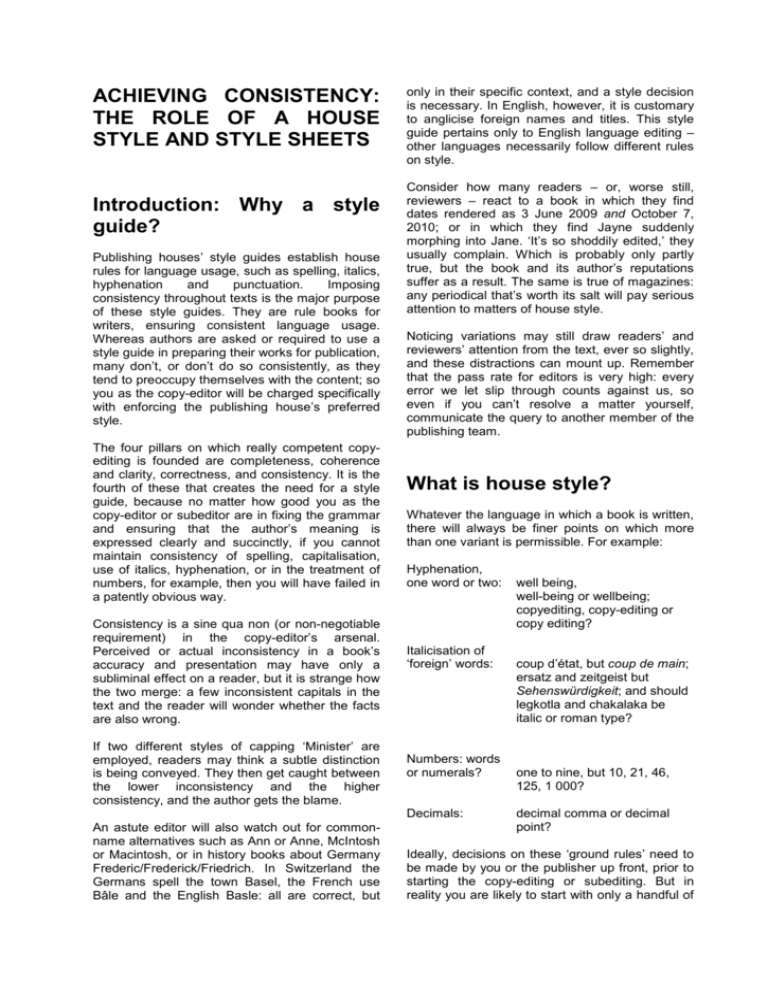

ACHIEVING CONSISTENCY: THE ROLE OF A HOUSE STYLE AND STYLE SHEETS Introduction: Why a style guide? Publishing houses’ style guides establish house rules for language usage, such as spelling, italics, hyphenation and punctuation. Imposing consistency throughout texts is the major purpose of these style guides. They are rule books for writers, ensuring consistent language usage. Whereas authors are asked or required to use a style guide in preparing their works for publication, many don’t, or don’t do so consistently, as they tend to preoccupy themselves with the content; so you as the copy-editor will be charged specifically with enforcing the publishing house’s preferred style. The four pillars on which really competent copyediting is founded are completeness, coherence and clarity, correctness, and consistency. It is the fourth of these that creates the need for a style guide, because no matter how good you as the copy-editor or subeditor are in fixing the grammar and ensuring that the author’s meaning is expressed clearly and succinctly, if you cannot maintain consistency of spelling, capitalisation, use of italics, hyphenation, or in the treatment of numbers, for example, then you will have failed in a patently obvious way. Consistency is a sine qua non (or non-negotiable requirement) in the copy-editor’s arsenal. Perceived or actual inconsistency in a book’s accuracy and presentation may have only a subliminal effect on a reader, but it is strange how the two merge: a few inconsistent capitals in the text and the reader will wonder whether the facts are also wrong. If two different styles of capping ‘Minister’ are employed, readers may think a subtle distinction is being conveyed. They then get caught between the lower inconsistency and the higher consistency, and the author gets the blame. only in their specific context, and a style decision is necessary. In English, however, it is customary to anglicise foreign names and titles. This style guide pertains only to English language editing – other languages necessarily follow different rules on style. Consider how many readers – or, worse still, reviewers – react to a book in which they find dates rendered as 3 June 2009 and October 7, 2010; or in which they find Jayne suddenly morphing into Jane. ‘It’s so shoddily edited,’ they usually complain. Which is probably only partly true, but the book and its author’s reputations suffer as a result. The same is true of magazines: any periodical that’s worth its salt will pay serious attention to matters of house style. Noticing variations may still draw readers’ and reviewers’ attention from the text, ever so slightly, and these distractions can mount up. Remember that the pass rate for editors is very high: every error we let slip through counts against us, so even if you can’t resolve a matter yourself, communicate the query to another member of the publishing team. What is house style? Whatever the language in which a book is written, there will always be finer points on which more than one variant is permissible. For example: Hyphenation, one word or two: Italicisation of ‘foreign’ words: Numbers: words or numerals? Decimals: An astute editor will also watch out for commonname alternatives such as Ann or Anne, McIntosh or Macintosh, or in history books about Germany Frederic/Frederick/Friedrich. In Switzerland the Germans spell the town Basel, the French use Bâle and the English Basle: all are correct, but well being, well-being or wellbeing; copyediting, copy-editing or copy editing? coup d’état, but coup de main; ersatz and zeitgeist but Sehenswürdigkeit; and should legkotla and chakalaka be italic or roman type? one to nine, but 10, 21, 46, 125, 1 000? decimal comma or decimal point? Ideally, decisions on these ‘ground rules’ need be made by you or the publisher up front, prior starting the copy-editing or subediting. But reality you are likely to start with only a handful to to in of guidelines and will then have to consult reference works in an ad hoc manner as you work through the text. Whatever decisions you take in supplementing house style, you must record them somewhere if they are to be applied consistently across an entire manuscript (don’t rely on memory, whatever you do!). That ‘somewhere’ is known as a style sheet, which should be applied to a specific publication. It could even be a notebook together with the page and line number for easy reference (eg when Jane de Wet (p 4) becomes Jane de Wit (p 28). And, naturally, style sheets are not static things; they grow organically with each new edition of a book or each subsequent issue of a magazine. Wherever you have to make choices on points of style, you will first need guidance and secondly need to record your decisions. The points in a text on which you will possibly have to make house style decisions include: spellings hyphenation quotations and quotation marks commas order of punctuation at the end of quotations and around a close parenthesis full points/stops numbers possessives bold dash (en-rule or em-rule) italics lists thousands elision of numbers abbreviations/contractions dates decimals cross-references capitalisation, especially in headings style of figure and table heads/captions style of note indicators in tables and text references and bibliographies. What house style is not What, then, is house style not? It must not be confused with either of the following equally important aspects of book and magazine production: Author’s style of writing: this can range from formal and/or stilted to anecdotal/informal, stream of consciousness or historical narrative, but this has nothing to do with house style, which is much more the concern of the editor seeking to impose a consistency of treatment of the items listed above throughout the author’s text. Design elements such as paragraph style (blocked or indented), list style (numbered or bulleted), type style (sans serif (eg Arial) or serif (eg Times Roman)) or style for quotations (either intext or displayed). These are all typographical and design decisions taken by a book designer. The copy-editor simply implements them. What contributes to a style guide? Your starting point needs to be the publisher’s preferred dictionary and, if they have one, an upto-date house style manual that sets out their inhouse style requirements. (If they don’t have one, standardise on your preferred UK/SA English dictionary.) For the sake of completeness or the voice of authority, add to these two resources any of the many style guides available, including: The Economist Style Guide The Guardian Style Book New Hart’s Rules New Oxford Dictionary for Writers and Editors Collins Dictionary for Writers and Editors Bryson’s Dictionary of Troublesome Words The Oxford Manual of Style MHRA Style Guide. Academic style for the arts and humanities published by the Modern Humanities Research Association; based in the United Kingdom Independent Newspaper Group’s manual of style heads/captions Government Communications Editorial Style Guide http://www.gcis.gov.za/ resource_centre/guidelines/styleguide/ editorial_styleguide_2011.pdf Handbook on referencing and other matters (Centre for Information Literacy, UCT) South African Law Journal Guide to Authors ACS Style Guide. Style for scientific papers published in journals of the American Chemical Society American Medical Association Manual of Style. Style for medical papers published in journals of the American Medical Association American Sociological Association Style Guide. Academic style for the social sciences by the American Sociological Association. APA style. Academic style for the social sciences by the American Psychological Association The Chicago Manual of Style. Style required by some academic publishers for books and journal publications MLA Style Manual and MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers. Academic style for the arts and humanities by the Modern Language Association of America Scientific Style and Format: The CSE Manual for Authors, Editors and Publishers, 7th edition. Style for scientific papers published by the Council of Science Editors (CSE), a group formerly known as the Council of Biology Editors (CBE) The New York Times Manual of Style and Usage. The first group above tends to follow British English; the second follows American English. In South Africa, unless our publisher insists otherwise, we tend to follow the British English because of our close links to it. Next in line in the armoury of reference books should be specialised dictionaries or word lists that cover the vocabulary of specialist areas: medicine, law, geology, archaeology, psychology, geosciences, environmentalism, art, electronics, engineering, physics, chemistry, avionics, transport, banking. The list is, of course, endless. Tap into these, whether paper-based or online, to check established or standard usage before you make style decisions. One of the worst things an editor can do is to impose either their own preferences or some general convention on particular disciplines or subject areas, because, in essence, they’re interfering with the ‘code language’ the members of that discipline or area regard as akin to a mother tongue. Tell a medical person, for instance, that ‘micro-organism’ must be spelt thus and not ‘microorganism’ and they might turn apoplectic. Or tell an economist that ‘bears’ and ‘bulls’ need not only elucidation but also quotation marks simply because you’re unfamiliar with the terms and you’ll only be exposing your own crass ignorance. In other words, try to tap into jargon wherever you need to, but at the same time you should ask yourself whether the targeted readership will understand it. If you can answer ‘yes’, leave it intact; if not, do what’s necessary as copy-editor to ensure that the uninitiated readership will find the terminology accessible. What is a style sheet and how is it different from a style guide? What follows below are two examples of style sheets to introduce the concept and the discussion that follows (figures 1A and 1B). These sample style sheets illustrate the two basic ways in which you can record the decisions made for a specific manuscript: in alphabetised cells in a table (Figure 1A; this is a style sheet in the process of compilation), or under meaningful headings (Figure 1B; this is a completed style sheet), whichever suits the project and/or you. Each has its merits, though one may lend itself better to a particular publication. Set them up as MS Word documents and populate them as you work through a manuscript – possibly amending them as you change your mind about earlier decisions as it becomes apparent were perhaps misguided or misinformed. You should then submit the style sheet together with the edited manuscript to your contact at the publisher so that your decisions accompany the text throughout the production process. Style sheet decisions: Book ABC A B C and, not & D E decimal comma, not en-rule point dash = emrule between number ranges: 49– 51 F G H I J/K L M N O P/Q Mussolini no-one, not em-rule no one for dash, Numbers: 1– spaced 9 = words S T U V R W well-being X Temp: velocity, not 16 ºC speed Y Z zeitgeist (lc, roman) Figure 1A Style sheet organised in alphabetised cells Other House style and consistency: Book XYZ Capital letters Hyphenation/one word First World abovementioned Third World co-operation/co-ordinate Parliament (singular/specific) common-law requirement the High Court decision e-commerce, but email focusing/focused in so far/inasmuch judgment (of court) multi-media online/offline policymaker pro-active radiocommunication roleplayer worldwide Lowercase Dates due diligence (report) 12 May 1865 the court decided 1994-–99 (en rule; elided) southern Africa parliaments (plural/general) Nomenclature: use only as appropriate Lists enterprise/business company/partnership/corporation Footnote numbers the sentence after a colon: first item; second item; third item, and final item Quotation marks follow end punctuation at the end of .8 or 9 singles; doubles inside singles the word ‘convergence’ means ... it states that ‘the term “electronic communication” is ...’ Words giving difficulty Punctuation social vs societal No stops with acronyms and abbreviations: ie, eg. ISNs, viz, telecommunication vs telecommunications enquiry (question) vs inquiry (official) as regards/regarding/with regard to consist of/comprise ECT Act ‘or’ is preferable to ‘/’ to show alternatives: ‘local or domestic markets’ not local/domestic markets’ Words giving difficulty Punctuation in terms of: avoid if possible A, B, C, etc (comma before ‘etc’) Impersonal voice Numbers No place to ‘I’, ‘We’ in legal writing: 1–9 in words use third person singular instead ‘it’: 10+ in numerals It is customary to ... No need to give both words and The law on this point is ... figures, as in a legal document The chapter examines ... (Not: ‘I shall examine ... I this chapter’) Figure 1B Style sheet organised under logical headings As stated above, when a consistency/house style query arises, you should first consult the client’s house style manual (or style guide, next their preferred dictionary and then any specific word lists pertaining to the subject-matter – in this order. The style sheet must accompany the manuscript and the page proofs on their journey through production. One reason for this is that much of the book’s structure and content is retained in the copy-editor’s short-term memory, and if they work on an MS in concentrated periods they might remember the oddest things about spellings and italics; but wait a week and it all disappears (and if they do retain it at all, that way lies madness!). So it will pay you to keep fuller notes than you would expect to be necessary – and the style sheet’s the pace to do so. A second reason for the style sheet’s taking this journey is that another proofreader, or the author or even the publisher (or commissioning editor), may spot apparent inconsistencies, and will need to know the decision you took and where you have deviated from it (frailty, thy name is ...). Sometimes the typesetter finds it useful to see this record of the editorial decisions too, to confirm and fix errors as they spot them. And even the indexer, right towards the end of the process, may need to consult the style sheet when they detect what seem to be spelling, hyphenation or capitalisation inconsistencies. This is what makes this ‘bible’ for each book such an indispensable tool. How – and why – do we maintain house style? Now on to the practicalities. Assume you’re now reading through the MS, pencil (or red pen) in hand. Because of the amount of detail you have to cope with, you’ve quickly learned to be proactive in this area, and you spot, say, ‘no one’ spelt as two words. Circle it in pencil at this point (an easyto-erase aide-memoire to return to). Perhaps stick a Post-it note or add a paper clip to this page to speed things up should you need to find the marked word again. Electronically, insert a Comment in the text. Later, you come across ‘noone’ and the alarm bells begin to ring ... ‘Hmm, didn’t I spot it as two words earlier?’ you ask yourself. Yes you did and you found at that point the day before that the dictionary gave both spellings as acceptable, and you opted for two words. Now, you know how to mark the second occurrence, don’t you? But say the process had worked differently. You’d retrace your steps and change the first occurrence to ‘no-one’, note it in the style sheet, and then mark all further occurrences to be consistent with that later decision. That’s all part and parcel of the editorial process. Being consistent yet openminded and flexible. Or you might even find that by far the majority of occurrences are ‘no one’ (two words). As long as the style guide or the dictionary says it’s acceptable, go with the majority – it’ll make your job a whole lot easier and more profitable, remember, and your client happier too. Now, whereas the decision to display a long quotation by indenting it from the left, inserting a blank line and below it, and setting it one point size smaller than the body text is a design one, the decision to insert it between single rather than double quotation marks (or inverted commas), or without any quotation marks, is a house style one. So is the decision where to place the final punctuation of the quoted text in relation to the close quotation marks. Consult the house style manual to ascertain the publisher’s preference, and follow that. If there’s no guidance, make your own decision based on the available resources – and adhere to it consistently. Ironically, you’re much more likely to be judged on whether you followed a house style decision consistently than on which decision you made – if only because inconsistencies are so much more visible! References: John Linnegar, Paul Schamberger & Jill Bishop Consistency, consistency, consistency: The PEG Guide to Style Guides (PEG, 2009) Carol Fisher Saller The Subversive Copy Editor: Advice from Chicago (Chicago University Press, 2009) Judith Butcher, Caroline Drake & Maureen Leech Butcher’s Copy Editing: The Cambridge Handbook for Editors, Copy-editors and Proofreaders (Cambridge University Press, 4 ed 2009)