CONSEQUENCES OF DEFORESTATION

advertisement

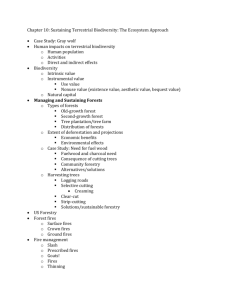

CONSEQUENCES OF DEFORESTATION In some cases, deforestation can be beneficial. Given the right mix of social needs, economic opportunities, and environmental conditions, it can be a rational conversion from one type of land use to a more productive one. The tragedy lies in the fact that most lands that have been deforested in recent decades are not suited for long-term farming or ranching and they quickly degrade once the forest has been cut and burnt. Unlike the fertile soils of temperate latitudes, most tropical forest soils cannot sustain annual cropping. The carrying capacity of the soil will not support intensive annual cropping without rapid, irreversible degradation. Similarly, intensive cattle grazing cannot be supported because grasses grown on forest soils do not have the same productivity levels as those on arable soils. In fact, there are very few forested soils in developing countries today that are available for future agricultural expansion, underscoring the urgent need to increase agricultural production on existing farmlands rather than converting more forests to farms. In many cases, political decision-makers knowingly permit deforestation to continue because it acts as a social and economic safety valve. By giving people free access to forested lands, the pressure is taken off politicians to resolve the more politically sensitive problems that face developing countries, such as land reform, rural development, power-sharing, and so on. Nonetheless, the problems do not go away. They persist as do the injustices associated with them. The social consequences of deforestation are many, often with devastating long-term impacts. For indigenous communities, the arrival of "civilization" usually means the destruction of their traditional life-style and the breakdown of their social institutions. Individual and collective rights to the forest resource have been frequently ignored and indigenous peoples and local communities have typically been excluded from the decisions that directly impact upon their lives. Many of the indigenous peoples of the Brazilian states of Amazonas and Rondônia have been encroached upon by slash-and-burn farmers, ranchers, and goldminers, often resulting in violent confrontations. The intrusion of outsiders destroys traditional life styles, customs, and religious beliefs. Watersheds that once supplied communities with their drinking water and farms with irrigation water have become subject to extreme fluctuations in water flow. The loss of safe, potable water puts communities' health at risk for a variety of communicable diseases. In economic terms, the tropical forests destroyed each year represent a loss in forest capital valued at $US 45 billion (Hansen, 1997). By destroying the forests, all potential future revenues and future employment that could be derived from their sustainable management for timber and non-timber products disappear. Probably the most serious and most short-sighted consequence of deforestation is the loss of biodiversity. The antiseptic phrase "loss of biodiversity" masks the fact that the annual destruction of millions of hectares of tropical forests means the extinction of thousands of species and varieties of plants and animals, many of which have never been catalogued scientifically. How many species are lost each year? The exact figure is not known, a consequence of our limited knowledge of tropical forest ecosystems and our inadequate monitoring systems. Some estimates put the annual loss at 50,000 separate species but this is an educated guess at best. Fragmented stands of trees left during deforestation are usually not large enough to be self-perpetuating in terms of maintaining even an altered balance of biodiversity. Deforestation is eroding this precious resource of biodiversity. Although there is some debate about the rate at which the atmosphere is warming, there is general agreement that it is warming. The currently accepted models predict a 0.3 degree Celsius increase per decade in global temperatures over the next century (Ciesla, 1995). This is due to the increase in the amount of carbon dioxide present in the atmosphere, which has risen by about 25 per cent in the last 150 years. Although it is less than 1/20 of one per cent of the earth's atmosphere, carbon dioxide has a high capacity to absorb radiant heat (Woodall, 1992). The negative consequences of global warming are catastrophic -- increasing drought and desertification, crop failures, melting of the polar ice caps, coastal flooding, and displacement of major vegetation regimes. The amount of carbon currently in the atmosphere is estimated to be about 800,000 million tons and is increasing at the rate of about 1 percent annually. Deforestation is an important contributor to global warming, however, its contribution relative to the other factors is not precisely known. The principal cause of global warming is the excessive discharges in industrialized countries of greenhouse gases, mostly from the burning of fossil fuels. Annual discharges from burning fossil fuels are estimated to be about 6,000 million tons of carbon, mostly in the form of carbon dioxide. It is thought that an additional 2,000 million tons or about 25 percent of the total carbon dioxide emissions are a consequence of deforestation and forest fires (WCFSD, 1997). At the regional level, deforestation disrupts normal weather patterns, creating hotter and drier weather. Unfortunately, efforts to find solutions to the deforestation crisis has not been as success in capturing investment money as have improvements to automotive exhaust emissions. The long term impact of deforestation on the soil resource can be severe. Clearing the vegetative cover for slash and burn farming exposes the soil to the intensity of the tropical sun and torrential rains. This can negatively affect the soil by increasing its compaction, reducing its organic material, leeching out its few nutrients available, increasing its aluminum toxicity of soils, making it marginal for farming. Subsequent cropping, frequent tillage, and overgrazing by livestock accelerate the degradation of the soil. In the dry forest zones, land degradation has become an increasingly serious problem, resulting in extreme cases in desertification. It affects about 3,000 to 3,500 million hectares, about one-quarter of the world's land area, and threatens the livelihoods of 900 million people in 100 countries of the developing world. Desertification is the consequence of extremes in climatic variation and unsustainable land use practices including overcutting of the forest cover. Growing populations are making ever-increasing demands on the land to produce more, leading to an intensification of use beyond the carrying capacity of the land. By 2050, two billion people, or 20 per cent of the world's population, will suffer from water shortages (WRI, 1994). Most of these people will be living in developing countries. Once denuded, the same watersheds lose their capacity to regulate stream flows and experience rapid fluctuations in stream and river levels, often resulting in disastrous downstream flooding. Water shortage is a major health risk in terms of inadequate sewage disposal, poor personal hygiene, and insufficient potable water. Food security is threatened as irrigation water becomes scarcer. Without the protection of the tree cover, soils are exposed to the rigors of severe tropical climates and are rapidly eroded. Freshwater and coastal fisheries are devastated by the high sedimentation loads carried by the rivers, as are wildlife-rich wetlands. Sedimentation from degraded watersheds is also one of the principal causes of the decline of coastal coral reefs. The economic and environmental costs are staggering.