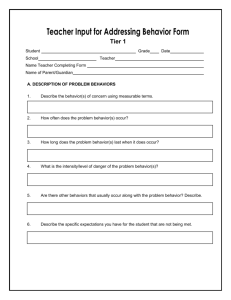

Writing Behavioral Intervention Plans (BIP) based on

advertisement