PET EFFECTS ON STATE-ANXIETY

advertisement

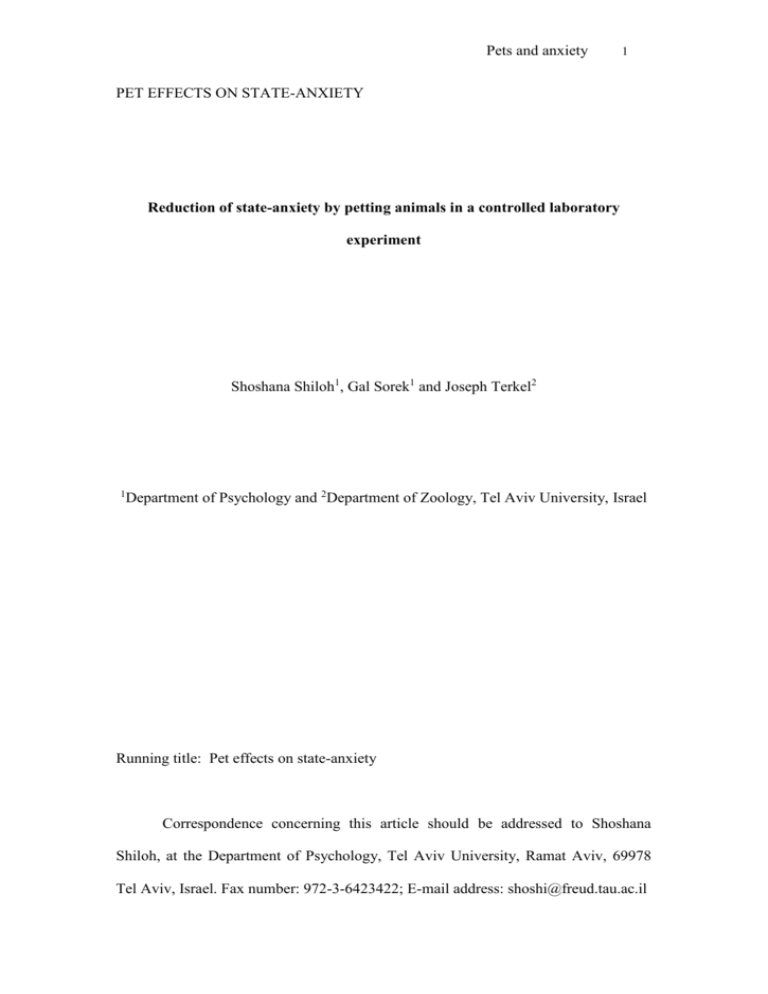

Pets and anxiety 1 PET EFFECTS ON STATE-ANXIETY Reduction of state-anxiety by petting animals in a controlled laboratory experiment Shoshana Shiloh1, Gal Sorek1 and Joseph Terkel2 1 Department of Psychology and 2Department of Zoology, Tel Aviv University, Israel Running title: Pet effects on state-anxiety Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Shoshana Shiloh, at the Department of Psychology, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv, 69978 Tel Aviv, Israel. Fax number: 972-3-6423422; E-mail address: shoshi@freud.tau.ac.il Pets and anxiety 2 Abstract The effect on anxiety of petting an animal and the underlying mechanisms of such an effect were examined by a repeated-measures, within-session experiment with 58 non-clinical participants. Participants were exposed to a stressful situation in the laboratory — the presence of a Tarantula spider, which they were told they might be asked to hold — and then randomly assigned to one of 5 groups: petting a rabbit, a turtle, a toy rabbit, a toy turtle, or to a control group. Participants’ attitudes towards animals were measured as potential moderators. State-anxiety was assessed at baseline, after the stress manipulation, and after the experimental manipulation. The main findings showed that petting an animal reduced state-anxiety. This effect could not be attributed to the petting per se, since it was observed only with animals and not with matched toys. The anxiety-reducing effect of petting an animal applied to both the soft cuddly animals and the hard-shelled ones. The anxiety-reducing effect applied to people with different attitudes towards animals and was not restricted to animal lovers. The discussion addresses possible emotional and cognitive foundations of the observed effects and their implications. Key words: state-anxiety, petting animals. Pets and anxiety 3 Reduction of state-anxiety by petting animals in a controlled laboratory experiment State-anxiety has been defined as a transitory emotional response involving unpleasant feelings of tension and apprehensive thoughts (Spielberger, 1966). It is often elevated in the presence of fear-arousing cues, and its control has been the target of many interventions. The present study focused on pet-assisted intervention for reducing anxiety, a method that has gained enthusiastic fans over the years but has suffered from insufficient scientific investigation. Reviews of the literature point to many potential psychological, social and health benefits of the human-animal bond (e.g.: Brasic, 1998; Cusak, 1988; Edney, 1995). Pets have been suggested to provide an unconditional source of affection, enhance self-esteem and emotional stability, reduce feelings of loneliness and isolation and help people socialize, provide pleasurable activity and assistance, are something to care for and a source of consistency and a sense of security (see e.g.: Edney, 1995; Katcher & Friedmann, 1980; McCulloch, 1984). Pets have also been suggested to serve a supportive function that buffers people against stress and illness (Allen, 1985). Among pet owners experiencing high levels of stress, interaction with pets was identified as an important stress management practice (Gage & Anderson, 1985). Owners of dogs, in particular, were buffered against the impact of stressful life events on physician utilization, as reflected in fewer doctor contacts during stressful life periods (Siegel, 1990). Other studies, however, failed to support the relationship between pet ownership and improved psychological health (Watson & Weinstein, 1993). These findings and assumptions were the background for the development of pet-facilitated psychotherapy, in which a pet is used as a co-therapist and becomes an Pets and anxiety 4 integral part of the treatment process (Barba, 1995; Levinson, 1965). Pet-assisted therapy has been adapted by practitioners in social work, marriage and family counseling, psychology, and psychiatry, and evaluated by them as an effective technique (Mason & Hagan, 1999). Animal-assisted programs for therapeutic interventions have been developed for special populations such as children and adolescents with various emotional, behavioral or mental problems (Mallon, 1992), and posttraumatic stress disorder patients (Altschuler, 1999); specific guidelines were developed for this purpose (e.g.,: Society for Companion Animal Studies, 1990). Among the benefits reported by therapists, we were especially interested in anxiety reduction. Barker and Dawson (1998) reported that interaction with a trained animal during a session of therapy reduced state-anxiety in psychiatric inpatients. When healthy children were examined by a doctor in a within-subject, time-series designed experiment, with and without a dog present, significantly greater reductions in behavioral distress and physiological parameters of stress were found when the dog was present (Nagengast, Baun, Megel, & Leibowitz, 1997). When the effects of interacting with a dog, reading aloud or reading quietly were assessed on measures of anxiety among college students, interacting with a dog or reading quietly lowered both physiological and psychological indicators of anxiety (Wilson, 1991). Taken together, these findings indicate that pet animals can reduce anxiety, especially in stressful situations. Several recent reviews have raised serious criticisms of the abundance of descriptive studies and the paucity of adequate quantitative methodology in this area. According to Brasić (1998), much of the published literature consists of anecdotal case reports, while studies utilizing experimental designs and statistical analysis are rare. Brodie & Biley (1999) found methodological difficulties stemming from the Pets and anxiety 5 complexity of the subject area, including poor design, small sample sizes, and failure to randomize. Much of the research has been conducted in the field rather than in controlled laboratory settings, with unclear control over extraneous variables. The fact that studies have been financially supported by special interest groups raises doubts about the objectivity of their conclusions (Brasić, 1998). The extent to which participants were stressed is also questionable in most of the studies, since standard experimental stressors were not used. A further complicating factor is that not all individuals have positive attitudes towards animals (Kidd & Kidd, 1989), and not all animals raise the same positive responses from people. Soft, hairy animals are known to be preferred and better liked than cold animals (Margadant-van Arcken, 1989). It is not known whether different types of animals and different attitudes of individuals moderate the benefits of interacting with animals. The present study was designed to extend our knowledge by adding: (1) a controlled experiment that would examine the specific effects of an animal on state anxiety among stressed, non-clinical individuals; (2) an examination of the significance of the nature and features of the animal in determining its stress-reducing effects; and (3) an evaluation of the possible moderating effects of interpersonal variance in attitudes towards animals on the effects of an animal. Three questions were asked: (1) Is the effect on anxiety due to the object being a live animal? This was studied by comparing the effect of holding and petting live animals to that of holding and petting matching toys, utilizing a randomized experimental design. (2) What types of pets are most effective? Are all pets equally effective, or is the potential effect specific to soft cuddly animals? This was studied by comparing petting a rabbit with petting a turtle, in a randomized experimental Pets and anxiety 6 design. (3) Is the effect of petting animals moderated by attitudes towards animals? We measured attitudes toward animals among all participants in our experiment, and looked for statistical interactions between experimental conditions and this variable. Methods Overview The study was designed as a repeated-measures, within-session experiment. Non-clinical participants were exposed to a stressful situation in the laboratory — the presence of a Tarantula spider, which they were told they might be asked to hold. They were then randomly assigned to one of 5 groups: petting either a rabbit, a turtle, a toy rabbit, or a toy turtle, or to a control group that got neither an animal or a toy. The animals were trained to be tolerant to petting. The toys matched the size and texture of the real animal. State-anxiety was measured 3 times: at baseline, after the stress manipulation, and after the experimental manipulation. Attitudes towards animals were assessed at the beginning of the session. Participants Fifty-eight individuals (35 women and 23 men) took part, mean age 26.16 years (SD = 6.83, range from 17 to 58). 45 were students at Tel Aviv University (34 undergraduates and 11 graduate students), and 13 were university employees. Measures Two standard questionnaires were used to measure state-anxiety and attitudes towards animals. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). (Speilberger, Gorsuch, & Lushene, (1970) measured the dependent variable, using the state-anxiety part that asks respondents to indicate how they feel right now. Twenty items describing feelings of tension, nervousness, worry and apprehension are rated on a 4-point scale. This Pets and anxiety 7 measure was found reliable and valid in numerous studies, including its Hebrew translation (Teichman, 1978). Its internal reliability in our sample ranged from Cronbach's alpha = 0.86 at baseline to 0.93 after the stress manipulation. The Companion Animal Semantic Differential. (Poresky, Hendrix, Mosier, & Samuelson, 1988) was used to measure our moderator variable. This 18-item scale measures attitudes toward pet animals using a 6-point semantic-differential format (hot – cold; good – bad; friendly – unfriendly, etc.). It was reported reliable and valid by its developers (Poresky, Hendrix, Mosier, & Samuelson, 1988). In our sample its internal reliability was Cronbach's alpha = 0.88, and its distribution was comparable to that reported in the American sample (means 89.64±12.07 and 94.37±10.80 respectively). Procedure Participants were recruited by notices posted around the university campus inviting participation in a study on attitudes towards animals for course credit or a small fee. After administering the Companion Animal Semantic Differential and the STAI to participants individually, the stress manipulation was conducted. We used a spider as a stress-arousing stimulus because of its face validity in the context of the study, and its high fear arousing potential among non-clinical populations (Arrindell, 2000). The experimenter (a female graduate student) uncovered a glass jar containing a Tarantula spider, and said: “This is a spider. The experiment has two groups: one will watch the spider, and the other will be asked to hold it. You will be told your assignment shortly. Now, I have to ask you to wait a minute while I get something from the next room”. The experimenter left the room for 2 minutes, returned and administered the STAI again. At this point the participant, who had been randomly assigned to one of the 5 groups, was handed one of the following: a rabbit (n=13), a Pets and anxiety 8 turtle (n=11), a toy rabbit (n=11), or a toy turtle (n=12), which had been covered until then. The subject was instructed “to hold and pet it for a while”. The control group (n=11) was asked to wait a little while longer while the experimenter left the room again. The uncovered glass jar containing the spider remained in the room the whole time. The petting/waiting period lasted for 2 minutes. The pet/toy was taken away by the experimenter, who administered the STAI for the third time. All participants were then told they would not have to hold the spider. At the end of the session a short interview was conducted on what they had done, felt and thought during the experiment. They were then debriefed and thanked. Results Manipulation check The mean state-anxiety score at baseline was 30.07 (SD=7.69) and rose to 36.07 (SD=11.09) after the stress manipulation. A repeated-measure analysis of this difference yielded significant results (t(1,57)=4.11, p<.001). The stress manipulation, therefore, effectively increased state-anxiety among the participants. Experimental effects Distributions of age, gender and attitudes towards animals (Table 1) did not differ among the groups (F(4,53)=0.65, Chi-Square=1.80, F(4,53)=0.50, n.s., respectively). -----------------------------------Insert Table 1 about here --------------------------------------Means and standard deviations of the three state-anxiety measures for each of the five groups are presented in Table 2. At baseline, there were no significant Pets and anxiety 9 ------------------------------------Insert Table 2 about here -------------------------------------differences among the 5 groups in state-anxiety mean scores (F(4,53)=1.42, n.s.). The differences among the groups in state-anxiety scores after the experimental manipulation were found significant using ANCOVA with baseline and post-stress anxiety scores as covariates, (F(4,51)=3.30, p<.05). The effect size was medium (Cohen's d=.58). Thus, the experimental manipulation was shown to have affected the participants’ state-anxiety. In order to determine the sources of the experimental effect, two contrasts were first compared: animals versus toys, and soft versus hard-shelled groups. Means and SDs of post manipulation state-anxiety of these contrasts are presented in Table 3. --------------------------------------------Insert Table 3 about here ------------------------------------------------Results of contrast analyses adjusted for baseline and post-stress manipulation anxiety show the animals-toys contrast to be significant (F(1,55)=4.51, p<.05), with a low effect-size (Cohen's d=0.31), while the soft versus hard-shelled contrast is not significant (F(1,55)=2.39, n.s.). In addition, the control group versus animals contrast was significant (F(1,55)=9.49, p<.01), while the contrast of control group versus toys was not (F(1,55)=1.87, n.s.). Thus, petting animals resulted in lower state-anxiety scores compared to petting toys, while the texture of the petted object had no effect. Nor was there a significant difference in state-anxiety between petting a real rabbit or a real turtle (F(1,55)=2.38, n.s.). Interactions with attitudes towards animals Pets and anxiety 10 Pearson correlations between attitudes and state-anxiety scores were nonsignificant (rs= .01, .12, and -.03, at baseline, after stress manipulation and after experimental manipulation respectively). Consequently, entering attitudes as a covariant in the overall analysis did not change the manipulation effect (F(4,50)=3.28, p<.05). This was also demonstrated by two-way between-subjects analysis of variance using a median split (at score 90.50) of the participants with high versus low attitudes towards animals. No significant interaction with experimental groups on postmanipulation anxiety was found (F(4,57)=1.39, n.s.). These findings do not support the moderating hypothesis of attitudes towards animals on the stress-reducing effects of petting animals. Discussion Our study demonstrated that a short period of petting an animal resulted in reduced state-anxiety among non-clinical individuals in a stressful situation. The experimental design ruled out the effect being due to the petting per se, since it was observed only with animals and not with matched toys. The anxiety-reducing effect of petting animals was also found to hold for hard-shelled animals like a turtle and was not limited only to soft cuddly animals, indicating that it was the quality of being alive rather than the texture of the object that produced the effect. Finally, our findings showed that the anxiety-reducing effect applies to people with different attitudes towards animals, and is not restricted to animal lovers. These findings correspond with those of a few previous experimental studies reporting positive effects on anxiety and distress associated with interacting with animals (Barker & Dawson, 1998; Nagengast, Baun, Megel, & Leibowitz, 1997; Wilson, 1991). Our findings refined and strengthened the previous ones by experimentally manipulating the stress and anxiety in the situation, and by adding Pets and anxiety 11 groups engaged with similar inanimate objects. A comparable control used in another study (not on anxiety) found that children with Down’s syndrome interacting with a real dog showed more sustained focus for positive and cooperative interactions than did children interacting with an imitation dog in controlled conditions under the direction of an adult (Limond, Bradshow, & Cormack (1997). How can this effect be explained? Psychoanalytic approaches suggest that the innate drive to associate with animals satisfies people’s emotional need for affiliation (Levinson, 1972). Animals are believed to relate to symbolic thought according to Jungian theory on archetypes and the unconscious (Henderson, 1999). Additional emotional gratification comes from animals’ non-evaluative support, which can reduce threat to the ego (Allen, Blascovich, Tomaka, & Kelsey, 1991). In our experiment, participants were instructed to hold and pet the animals/objects. There is evidence that touching another living thing (pets and humans) engenders positive feelings and reduces stress, pain and anxiety (e.g., Lafreniere, et al., 1999; Montagu, 1978; Spence & Olson, 1997). The relaxing and comforting emotion induced by touching and petting an animal can, therefore, account for our findings. Although some studies show that touch per se is not necessary for achieving the positive effects of animals, and that similar effects can be obtained from the mere presence of animals, like watching an aquarium filled with fish (e.g.: Cole & Gawlinski, 1995), we did not differentiate between the effects of touching and the mere presence of an animal. Such a distinction is recommended in future experiments. Another potential mechanism underlying our findings may be cognitive. Brickel (1982) suggested an ‘attentional shift hypothesis’, according to which pets divert attention from an anxiety-generating stimulus, helping alleviate anxiety. Pets and anxiety 12 Evidence that distraction is effective in diminishing anxiety supports this hypothesis (Wilkins, 1971). Pet animals are ideally suited for a distraction role because of their appealing characteristics. They are complex, unpredictable, interactive, and operate on tactile, auditory, visual, and probably other levels. The mediational role of attention in anxiety has been supported by some researchers (Clark, 1999; Penfold & Page, 1999), and rejected by others (Allen, Blascovich, Tomaka, & Kelsey, 1991; Harris, & Menzies, 1998). Our findings, while compatible with the ‘attentional shift hypothesis’, do not preclude other underlying mechanisms such as the aforementioned emotional processes. Studies directly examining the hypothesis that the petting effect is mediated by distraction are strongly recommended. In conclusion, it might be appropriate at this stage to assume that both emotional and cognitive mechanisms, separately or in combination, can potentially explain our results. Further research applying carefully controlled methodology is necessary to reveal and separate the contributions of various causal factors. Limitations of the study. Generalizations should be drawn from our results with caution. One limitation concerns the specific animals considered. Different animals have different characteristics, and compatibility between people and their pets on physical, behavioral and psychological dimensions was found to be related to the owners’ mental and physical health (Budge, Spicer, Jones, & George, 1998). Despite our failure to find interactions between attitudes towards animals and the effects of petting, we should bear in mind that we tested only two, small, friendly pets. An unsuitable, unhealthy, poorly behaved, nervous animal can be hazardous both physically and psychologically to the individual (Duncan, 1998; Edney, 1995). The absence of an interaction between the anxiety reducing effect and attitudes towards animals may be due to a restriction of the range of attitudes in our Pets and anxiety 13 sample. The distribution of scores in CASD was skewed, and may indicate that only those favorably predisposed towards animals participated in the study. A more balanced sample may be needed in order to test the interaction hypothesis. Other interpersonal differences in traits that were not investigated in the present research may also moderate the effect of petting. Replications of our results with different pets, individuals and moderating variables, and including behavioral/avoidance and physiological measures of anxiety are also desirable. Also, the design of our experiment, in which participants were left alone in the room, did not allow a direct check that participants actually followed the experimenter's instruction "to hold and pet" the animal. Consequently, it may be more accurate to conclude that holding and/or petting an animal produced the observed effects. Another issue that should be addressed is the type of stress alleviated by pets in our experiment. In another laboratory study, researchers failed to find reduced state-anxiety and arousal among male students interacting with a dog during a stressful speech task compared to a control group (Straatman, Hanson, Endenburg, & Mol, 1997). They concluded that the stress of the speech task and the laboratory setting overrode the influence of the pet. More research is required to map the types and intensities of stress situations that are suitable for pet-assisted interventions. Finally, it has been argued that the high degree of experimental control characteristic of laboratory-based research often fails to yield a source of clinically relevant information that can be extrapolated to natural conditions (Chorpita, 1997). Generalizing from a non-clinical sample has also been questioned. In our study, even after the anxiety arousing manipulation, levels of anxiety did not reach clinical levels. However, in a summary of a mini-series of papers on laboratory research on anxiety, Pets and anxiety 14 Eifert, Forsyth, Zvolensky & Lejuez (1999) concluded that experimental research is both relevant and indispensable for the continued advancement of our understanding and treatment of anxiety. They also stated that creating clinically relevant phenomena in populations without known pathology permits a “cleaner” examination of the variables and processes involved. We adopt these views, and encourage the development of more interdisciplinary non-conventional co-operations, like ours, between professionals and researchers from different perspectives, from nursing through psychotherapy to zoology and veterinary medicine, attracted by similar questions. Such an endeavor presents a great challenge, and can be both exciting and fruitful to all involved. Pets and anxiety 15 References Allen, K.M. (1985). The human-animal bond. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press. Allen, K.M., Blascovich, J., Tomaka, J., & Kelsey, R.M. (1991). Presence of human friends and pet dogs as moderators of autonomic responses to stress in women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 582-589. Altschuler, E.L. (1999). Pet-facilitated therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 11, 29-30. Arrindell, W.A. (2000). Phobic dimensions: IV. The structure of animal fears. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38, 509-530. Barba, B. (1995). A critical review of research on the human/companion animal relationship 1988-93. Anthrozoös, 8, 9-15. Barker, S.B., & Dawson, K.S. (1998). The effects of animal-assisted therapy on anxiety ratings of hospitalized psychiatric patients. Psychiatric Services, 49, 797801. Brasić, J.R. (1998). Pets and Health. Psychological Reports, 83, 1011-1024. Brickel, C.M. (1982). Pet-facilitated psychotherapy: a theoretical explanation via attention shifts. Psychological Reports, 50, 71-74. Brodie, S.J., & Biley, F.C. (1999). An exploration of the potential benefits of pet-facilitated therapy. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 8, 329-337. Budge, R.C., Spicer, J., Jones, B., & George, R.S. (1998). Health correlates of compatibility and attachment in human-companion animal relationships. Society & Animals, 6, 219-234. Pets and anxiety 16 Chorpita, B.F. (1997). Since the operant chamber: are we still thinking in Skinner boxes? Behavior Therapy, 28, 577-583. Clark, D.M. (1999). Anxiety disorders: why they persist and how to treat them. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 37, s5-s27. Cole, K., & Gawlinski, A. (1995). Animal assisted therapy in the intensive care unit. Research Utilisation, 30, 529-536. Cusak, O. (1988). Pets and mental health. N.Y.: The Haworth Press Inc. Davis, J.H., & Juhasz, A. McC. (1984). The human/companion animal bond: how nurses can use this therapeutic resource. Nursing and Health Care, 5, 496-501. Duncan, S.L. (1998). The importance of training standards for service animals. In: C.C. Wilson and D.C. Turner (Eds.), Companion animals in human health. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. pp. 251-266). Edney, A.T. (1995). Companion animals and human health: an overview. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 88, 704-708. Eifert, G.H., Forsyth, J.P., Zvolensky, M.J., & Lejuez, C.W. (1999). Moving from the laboratory to the real world and back again: increasing the relevance of laboratory examinations of anxiety sensitivity. Behavior Therapy, 30, 273-283. Gage, M.G., & Anderson, R.K. (1985). Pet ownership, social support, and stress. Journal of the Delta Society, 2, 64-71. Harris, L.M., & Menzies, R.G. (1998). Changing attentional bias: Can it effect self-reported anxiety? Anxiety Stress and Coping, 11, 167-179. Pets and anxiety 17 Henderson, S.J. (1999). The use of animal imagery in counseling. American Journal of Art Therapy, 38, 20-26. Jorgenson, J. (1997). Therapeutic use of companion animals in health care. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 29, 249-254. Katcher, A.H., & Friedmann, E. (1980). Potential health value of pet ownership. Compendium of Continuing Education Practice Vet, 2, 117-121. Kidd, A.H. & Kidd, R.M. (1989). Factors in adults attitudes toward pets. Psychological Reports, 65, 903-910. Lafreniere, K.D., Mutus, B., Cameron, S., Tannous, M., Giannotti, M., AbuZahra, H., & Laukkanen, E. (1999). Effects of therapeutic touch on biochemical and mood indicators in women. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 5, 367-370. Levinson, B.M. (1965). Pet psychotherapy: use of household pets in the treatment of behavior disorder in childhood. Psychological Reports, 17, 695-698. Levinson, B.M. (1972). Pets and human development. Springfield, IL: Thomas, 1972. Limond, J.A., Bradshaw, J.W.S., & Cormack, K.F.M. (1997). Behavior of children with learning disabilities interacting with a therapy dog. Anthrozoös, 10, 8489. Lynch, J.J. (1985). The language of the heart. New York: Basic Books. Mallon, G.P. (1992). Utilization of animals as therapeutic adjuncts with children and youth – a review of the literature. Child & Youth Care Forum, 21, 53-67. Pets and anxiety 18 Margadant-van Arcken, M. (1989). Environmental education, children, and animals. Anthropozoös, 3, 14-19. Mason, M.S., & Hagan, C.B. (1999). Pet-assisted psychotherapy. Psychological Reports, 84, 1235-1245. McCulloch, W. (1984). An overview of the human-animal bond: present and future. In: Anderson, R.K., Hart, B.L., & Hart, L.A. (Eds.). The pet connection: Its influence on our health and quality of life. St. Paul, MN: Globe. pp.30-35. Montagu, A. (1978). Touching. New York: Harper and Row. Nagengast, S.L., Baun, M.M., Megel, M., & Leibowitz, J.M. (1997). The effects of the presence of a companion animal on physiological arousal and behavioral distress in children during a physical examination. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 12, 323-330. Penfold, K., & Page, A.C. (1999). The effect of distraction on within-session anxiety reduction during brief in vivo exposure for mild blood-injection fears. Behavior Therapy, 30, 607-621. Poresky, R.H., Hendrix, C., Mosier, J.E., & Samuelson, M.L. (1988). The companion animal semantic differential – long and short form reliability and validity. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 48, 255-260. Siegel, J.M. (1990). Stressful life events and use of physician services among the elderly: the moderating role of pet ownership. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 1081-1086. Pets and anxiety 19 Society for Companion Animal Studies. (1990). Guidelines for the introduction of pets in nursing homes and other institutions. Glasgow, UK: Straight Line Publ. Spence, J.E., & Olson, M.A. (1997). Quantitative research on therapeutic touch – an integrative review of the literature 1985-1995. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 11, 183-190. Spielberger, C.D. (1966). Anxiety and behavior. New York: Academic Press. Spielberger, C.D., Gorsuch, R.L., & Lushene, R.L. (1970). State-trait anxiety manual. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychological Press. Straatman, I., Hanson, E.K.S., Endenburg, N., & Mol, J.A. (1997). The influence of a dog on male students during a stressor. Anthrozoös, 10, 191-197. Teichman, Y. (1978). Affiliative reaction in different kinds of threat situations. In: C.D. Spielberger and I.G. Sarason, (eds.), Stress and Anxiety, Vol. 5. (pp.131144). Washington: Halsted Press. Watson, N.L., & Weinstein, M. (1993). Pet ownership in relation to depression, anxiety, and anger in working women. Anthrozoös, 6, 135-138. Wilkins, W. (1971). Desensitization: social and cognitive factors underlying the effectiveness of Wolpe’s procedure. Psychological Bulletin, 76, 311-317. Wilson, C.C. (1991). The pet as an anxiolytic intervention. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases, 179, 482-489. Pets and anxiety 20 Authors’ notes Shoshana Shiloh, Department of Psychology, Tel Aviv University; Gal Sorek, Department of Psychology, Tel Aviv University, Joseph Terkel, Department of Zoology, Tel Aviv University, Israel. This study was done in partial fulfillment of the Master's Degree thesis of the second author. We want to thank Shani Doron for her excellent assistance in data collection, and our colleagues at the Zoological park at Tel Aviv University for their cooperation. We would also like to acknowledge Keren Hadzdakah in name of Bracha and Motti Blisser, and Yad Hanadiv Foundation for partially supporting the present research. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Shoshana Shiloh, at the Department of Psychology, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv, 69978 Tel Aviv, Israel. Fax number: 972-3-6423422; E-mail address: shoshi@freud.tau.ac.il Pets and anxiety 21 Table 1 Demographic variables and attitudes toward animals according to experimental groups Age Rabbit Turtle Toy-rabbit Toy-turtle Control n=13 n=11 n=11 n=12 n=11 27.00±7.00 23.00±4.00 26.00±4.00 28.00±6.00 27.00±11.00 8/5 8/3 7/4 7/5 5/6 86.08±18.40 90.36±8.69 92.64±10.24 90.33±9.72 85.82±21.21 Gender (F/M) Attitude toward animals Pets and anxiety 22 Table 2 Means and standard deviations of three measures of state-anxiety according to experimental groups State anxiety Rabbit Turtle Toy-rabbit Toy-turtle Control measure: n=13 n=11 n=11 n=12 n=11 Baseline 29.69±5.31 32.18±9.49 32.91±8.26 29.08±7.74 26.64±7.16 36.54±6.28 33.27±10.76 37.27±14.06 37.17±14.86 35.91±9.28 28.54±7.33 28.91±7.93 34.36±8.02 Post stress manipulation Post experimental manipulation 32.09±10.82 34.33±9.39 Pets and anxiety 23 Table 3 Means and standard deviations of state-anxiety according to animals - toys and softshelled - hard-shelled contrasts n Mean Standard Deviation Animals 23 28.71 7.45 Toys 23 33.82 9.44 Soft 24 30.70 8.75 Hard-shelled 23 31.73 8.96