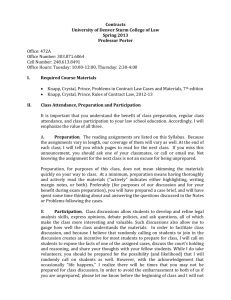

CONTRACTS REVIEW - NYU School of Law

advertisement