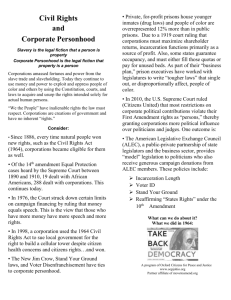

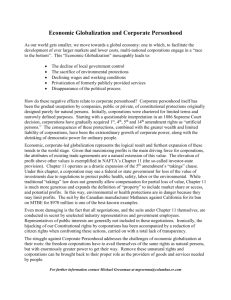

Corporate Complicity in Human Rights Violations – A discussion paper

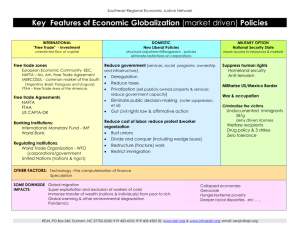

advertisement