The Effect of a Brief Mindfulness Exercise and Math Anxiety on State

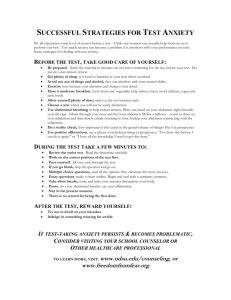

advertisement

Running head: MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY The Effect of a Brief Mindfulness Exercise and Math Anxiety on State Anxiety Olivia K. Eckhoff University of Wisconsin-Platteville 1 MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY 2 Abstract Mindfulness is a form of non-judgmental awareness (Kabat-Zinn, 2005) that has been shown to decrease stress and anxiety (Greeson, 2008); however, little is known about the benefits of very brief practice. This research examined the effects of mindfulness and self-reported math anxiety on state anxiety after 10 minutes of mindfulness exercise. In two experiments, participants completed a survey and pre-test measures of anxiety, listened to a 10-minute mindfulness exercise, and completed a post-test measure of state anxiety. In study 1, participants with high math anxiety showed a significantly greater reduction in state anxiety than participants with low math anxiety. However, there was as no significant differences in state anxiety among the different mindfulness exercises. Also, math anxiety had less of an effect for individuals with high mindfulness. In study 2, reduction in anxiety symptoms varied by gender and whether or not participants had received counseling for anxiety. Females who received counseling showed a greater reduction than females who had not received counseling; however, there was no difference in reduction for males. MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY 3 The Effect of a Brief Mindfulness Exercise and Math Anxiety on State Anxiety College students experience considerable stress and anxiety, especially first generation college students. A student’s ability to manage daily stressors directly impacts both academic performance and overall health. How can college students manage their stress and anxiety more effectively? Emotion regulation describes “a set of processes whereby people seek to redirect the spontaneous flow of their emotions” (Koole, 2010, p. 129). Theorists have established that an individual’s evaluation of a situation triggers emotion, but the situation alone does not (Gross, 1999). Koole (2010) identified two common strategies for regulating our emotions: bodily and cognitive strategies. Bodily strategies incorporate breathing and relaxation. Cognitive strategies include attention and reappraisal, which involves changing how we view a situation in a way that reduces negative emotional response. Both bodily and cognitive strategies are effective for reducing stress and anxiety (Koole, 2010). The current study considers whether emotion regulation strategies can be used to reduce math anxiety. An alternative approach to emotion regulation, that integrates both bodily and cognitive strategies, is mindfulness, which is defined as the non-judgmental awareness of the present moment (Kabat-Zinn, 2005). Mindfulness is a self-regulation strategy that decreases emotional distress, increases quality of life, and promotes optimal health (Greeson, 2008). According to Kabat-Zinn (2005), attention, emotion regulation, body awareness, and shift of perspective on the self, are skills that anyone can learn and practice in everyday settings in order to more effectively manage life’s daily stressors. Research on mindfulness has shown that mindfulness reduces stress and stress-related illnesses in both clinical and student populations; mindfulness is also associated with cognitive, emotional, biological, and behavioral changes (Greeson, 2008). MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY 4 Neuroimaging studies have found that mindfulness is linked to structural changes in specific areas of the brain believed to improve self-regulation and reduce emotional reactivity (Hölzel et al., 2011). Although past research has demonstrated effects of mindfulness on stress and well-being, few studies have considered how mindfulness could help math anxiety. Math anxiety is “a feeling of tension, apprehension, or fear that interferes with math performance” (Ashcraft, 2002, p. 181) that is experienced by many college students. Individuals with high levels of math anxiety tend to avoid math classes, receive lower grades in math classes, have negative attitudes toward math, and have negative self-perceptions (Akin & Kurbanoglu, 2011; Ashcraft, 2002). Consequently, students with math anxiety receive lower scores on standardized tests, though only a weak correlation exists between math anxiety and overall intelligence. Despite evidence that math anxiety is separate from other anxieties, individuals with math anxiety are more likely to score high on other anxiety tests, and women are more likely to have math anxiety than men (Ashcraft, 2002). Some researchers have argued that math-anxious students’ math scores are lower because of their anxiety towards the math – not their lack of math skills alone (Akin & Kurbanoglu, 2011; Ashcraft, 2002). According to processing efficiency theory, anxiety interferes with ongoing working memory due to one’s attention to anxious thoughts rather than the immediate task (Eysenck & Calvo, 1992 as cited by Ashcraft, 2002); similarly, math anxiety hinders math performance when individuals focus on their distracting thoughts instead of the math problems themselves. Ashcraft and Kirk (2001) provided support for this theory by showing that math anxiety involves interference with working memory. Moreover, a functional MRI study on children found an over-activity in areas of the brain associated with regulating negative emotions MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY 5 (Young, Wu, & Menon, 2012). This suggests that if students could more effectively regulate their negative emotions toward doing math, they could overcome their math anxiety. Therefore, mindfulness, an emotion regulation strategy, may be especially helpful for individuals with math anxiety. The effect of mindfulness on reducing stress and anxiety has been widely demonstrated, but there is some question as to the amount of mindfulness training needed to produce beneficial effects. Rosenzweig, Reibel, Greeson, Brainard, and Hojat (2003) found that, after practicing mindfulness twenty minutes per day for ten weeks, medical students experienced less anxiety and depression and a higher state of overall well-being. Several other studies have found these benefits in even shorter interventions (Flugel Colle, Vincent, Cha, Loehrer, Bauer, WahnerRoedler, 2010; Greeson, 2008; Harnett, Whittingham, Puhakka, Hodges, Spry, & Dob, 2010; Tang, Ma, Wang, Fan, Feng, Lu, Yu, Sui, Rothbart, Fan, & Posner, 2007). Harnett et al. (2010) found that after three 2-hour sessions of mindfulness practice (e.g. body scan, breathing, etc.), one-third of participants showed reduced stress levels linked to mindfulness. Furthermore, Tang et al. (2007) had participants complete five 20-minute mindfulness sessions, in which participants showed a decrease in anxiety and stress-related cortisol. Although research on mindfulness has shown that relatively short mindfulness interventions can reduce anxiety, little is known about the effectiveness of a single, brief mindfulness intervention, especially regarding students with math anxiety. The goal of the present study was to examine how a brief mindfulness exercise and level of math anxiety will influence students’ state anxiety. After completing pre-test measures, participants will complete a 10-minute mindfulness exercise (breathing / body scan), perform several math problems, and then do a post-test measure of anxiety. First, it is predicted that MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY 6 participants who do the brief mindfulness exercise will have a greater reduction in state anxiety than participants in the wait-list control group. It is expected that participants who do a breathing exercise will have a greater reduction in state anxiety than participants who do a body scan. Second, it is expected that participants with high math anxiety will show greater reduction in state anxiety than participants with low math anxiety. Lastly, it is predicted that the effect of a brief mindfulness exercise will vary according to level of math anxiety. For example, the effect of the brief mindfulness exercise will be greater for participants who have high math anxiety than participants with low math anxiety. Experiment 1 Method Participants Ninety-two undergraduate students, 56 males, 33 females, and 3 unreported, (Mage = 18.9 years, SD = 1.08, age range: 18-23 years) enrolled in General Psychology participated in the study. Participants were predominantly white, reflecting the demographics of the local community. Students received course credit for participation, though an alternate exercise was provided for students who do not wish to participate. Design The study had a 3 x 2 factorial design. The first independent variable was the brief mindfulness exercise with three levels (breathing, body scan, control), which was a betweensubjects variable. The second independent variable was the level of math anxiety (high, low), which was a quasi-experimental variable. The main dependent variable was the change in state anxiety before and after the mindfulness exercise. Materials MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY 7 The stimulus presented to participants was a 10-minute excerpt from a mindfulness exercise CD, either a “Mindfulness of Breathing” or “Full Body Mindfulness” exercise (“Mindfulness for Beginners”; Kabat-Zinn, 2005). The breathing exercise suggested that listeners place full awareness on one’s own breath, to notice how often the mind wanders, and to bring one’s attention gently back to the breath after it has shifted. The body scan exercise emphasized that listeners include the experiences of the body as a whole into awareness, that participants allow specific sensations to be brought into attention, and to recognize thoughts as thoughts. The questionnaire presented to participants contained a total of 65 questions including demographic information (age, sex, year in school, general background, math history), Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R; Feldman, Hayes, Kumar, Greeson, & Laurenceau, 2007), Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ; Gross & John, 2003), Math Evaluation Anxiety scale (MEA; Plake & Parker, 1982), and items from State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Kabacoff, Segal, Hersen, & Van Hasselt,1997) and Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS; Lovibond &Lovibond, 1995) for measures of trait and state stress and anxiety. All responses were rated on a 1-8 scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree; however, the MEA was rated from low anxiety to high anxiety. There were two general background questions, “Have you ever sought counseling?” and “Have you ever taken medication for anxiety?” and two math history questions, “How many math classes have you taken in college?” and “What is the highest level of math class that you have taken?” The CAMS-R and ERQ inquired about attention and emotion regulation tendencies by asking participants to rate the degree to which they agreed with statements, such as “I am easily distracted,” and “I keep my emotions to myself”. Trait Stress and Anxiety (TSA) items MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY 8 from the STAI and DASS asked participants to rate the degree to which they agreed with statements such as, “I find it difficult to relax,” in order to determine participants’ trait tendencies towards stress and anxiety. Pre-Post State Anxiety statements asked about participants’ immediate states of stress and anxiety with statements such as “I am tense”. The MEA asked participants to rate items in terms of how anxious participants felt during a specific event, such as “Getting ready to study for a math test”. Procedure A female experimenter conducted four 30-minute small group sessions in a classroom setting. Participants were randomly assigned to the experimental group (breathing / body scan) or a wait-list control group. The experimenter first described the study and obtained consent from participants. All participants completed the questionnaire, but participants in the experimental group paused before the final ten measures of post-state anxiety and listened to one of the two 10-minute excerpts from the mindfulness exercise CD, and participants in the experimental group returned to the post-state anxiety measures. Participants in the control group completed the entire questionnaire and had an opportunity to do the mindfulness exercise after the post-test measure of state anxiety. Finally, the experimenter provided a debriefing form, answered questions, and thanked the students for participating. Results It was hypothesized that a brief mindfulness exercise would influence participants’ state anxiety. Specifically, participants who did the breathing exercise were expected to show a greater reduction in state anxiety than participants who did the body scan exercise. In addition, participants who did the body scan exercise were expected to show a greater reduction in state anxiety than participants in a control condition who did not practice the brief mindfulness MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY 9 exercise. It was also predicted that participants’ level of math anxiety would influence state anxiety. Specifically, participants with high math anxiety were expected to have a greater reduction in state anxiety than participants with low math anxiety. Furthermore, it was hypothesized that the effect of a brief mindfulness exercise would vary according to participants’ level of math anxiety. The effect of a brief mindfulness exercise was predicted to be greater for participants who had high math anxiety than participants who had low math anxiety. These hypotheses were tested with a 3 (Brief Mindfulness Exercise) x 2 (Math Anxiety) independent samples ANOVA. Pairwise correlations were conducted to examine the relations between the mindfulness measure (CAMS-R), emotion regulation (ERQ), and trait-state anxiety (TSA). There was a positive relationship between CAMS-R and ERQ reappraisal r(90) = .37, p < .001 and a negative relationship between CAMS-R and TSA r(90) = -.45, p < .001. The ANOVA showed no main effect of the mindfulness exercise on state anxiety, F(2, 77) = 0.75, p = .48. There were no significant differences in reduction of state anxiety between participants who listened to the breathing exercise (M = 0.22, SD = 0.94), participants who listened to the body scan exercise (M = 0.67, SD = 1.29), and participants in the control group (M = 0.41, SD = 1.07). However, there was a significant main effect of math anxiety on state anxiety, F(1, 77) = 4.53, p = .036. Participants who had high math anxiety (M = 0.70, SD = 1.23) showed a significantly greater reduction in state anxiety than participants with low math anxiety (M = 0.14, SD = 0.91). Counter to prediction, there was no interaction of Brief Mindfulness Exercise by Math Anxiety on state anxiety, F(2, 77) = 0.32, p = .73, as shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY 10 Contrary to predictions, tests of the simple main effects showed that there was no significant effect of mindfulness exercise for the individuals with high math anxiety, (F < 1.0). Participants high in math anxiety showed no difference in reduction of state anxiety according to the type of mindfulness exercise (Ms = 0.34, 0.84 0.88, SDs = .98, 1.25, 1.5; breathing, body scan, control, respectively). Similarly, there was no simple main effect of mindfulness exercise for the individuals with low math anxiety, (F < 1.0). Discussion The results showed that, as expected, participants with high math anxiety showed a significantly greater reduction in state anxiety than participants with low math anxiety. However, anxiety did not vary according to type of mindfulness exercise. Contrary to predictions, there was no significant difference in reduction of state anxiety among participants who listened to the breathing exercise, the body scan exercise, or those in the control group. Furthermore, the effect of mindfulness exercise did not vary for individuals high in math anxiety or low in math anxiety. As predicted, women were more likely than men to have high math anxiety, and participants with high mindfulness scores on CAMS-R tended to have high scores on the ERQ measure of reappraisal as a strategy of emotion regulation. Interestigly, the effect of mindfulness practice and math anxiety varied according to an individual’s level of mindfulness. Trait mindfulness appeared to offset the effect of an individual’s level of math anxiety. An alternative explanation for the lack of difference between conditions may have been an ineffective control group. Due to time constraints, the participants did not complete any math problems. Consequently, the control group completed the pre-state anxiety measures and immediately completed the post-states anxiety measures, while the breathing and body scan groups listened to the mindfulness exercise between the state anxiety measures. This may have MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY 11 created an incomparable control condition. Another potential limitation was that the measure of Math Evaluation Anxiety (MEA) was not specific enough to measure the anxiety of doing math problems. The current study’s measure included questions that asked about participants typical reactions to doing math, but did not directly measure their anxiety before having to do math problems. One question for future research is whether women might show a greater capacity for anxiety reduction, as they tend to have higher levels of math anxiety. Experiment 2 Method Participants Ninety-six undergraduate students, 42 males, 52 females, and 2 unreported, (Mage = 20.33 years, SD = 2.00, age range: 18-34 years) enrolled in General Psychology participated in the study. Participants were predominantly white, reflecting the demographics of the local community. Students received course credit for participation, though an alternate exercise was provided for students who do not wish to participate. Design The study had a 2 x 2 factorial design. The first independent variable was the brief mindfulness exercise with two levels (mindfulness, audiobook control), which was a betweensubjects variable. The second independent variable was whether participants had received counseling for anxiety previously (yes, no), which was a quasi-experimental variable. The main dependent variable was the reduction in negative symptoms of anxiety before and after the mindfulness exercise. Materials MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY 12 The stimulus presented to participants were two 15-question math quizzes and a 10minute mindfulness exercise CD, either Insight Meditation (Salzberg & Goldstein, 2002) or an audiobook control entitled The Mind and the Brain (Schwartz & Begley, 2002). The insight meditation CD focused on both the breath and bodily sensations; whereas, the audiobook control was simply a narrator reading topics in psychology. The questionnaire presented to participants contained a total of 95 questions including demographic information (age, sex, year in school, general background, math history, anxiety medication history, counseling history), Trait Stress and Anxiety (TSA; Kabacoff, Segal, Hersen, & Van Hasselt,1997), Math Evaluation Anxiety scale (MEA; Plake & Parker, 1982), Math Anxiety Scale Revised (MAS-R, Bai, Wang, Pei, & Frey, 2009), Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R; Feldman, Hayes, Kumar, Greeson, & Laurenceau, 2007), Short Version of Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI; Walach, et al., 2006), Rapid Assessment of Well-Being – Short Depression and Happiness Scale (SDHS; Joseph, Linley, Harwood, Lewis, & McCollom, 2004), and items from and Pre-Post Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis, L.R. & Melisaratos, N., 1983) Responses were rated on a 1-8 scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. There were two general background questions, “Have you ever sought counseling?” and “Have you ever taken medication for anxiety?” and two math history questions, “How many math classes have you taken in college?” and “What is the highest level of math class that you have taken?” Trait Stress and Anxiety (TSA) items asked participants to rate the degree to which they agreed with statements such as, “I find it difficult to relax,” in order to determine participants’ trait tendencies towards stress and anxiety. The MEA asked participants to rate items in terms of how anxious participants felt during a specific event, such as “Getting ready to MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY 13 study for a math test”. The CAMS-R inquired about attention and emotion regulation tendencies by asking participants to rate the degree to which they agreed with statements, such as “I am easily distracted.” The FMI showed statements such as whether participants were “able to appreciate” themselves. The SDHS contained statements such as, “I feel satisfied with the way I am.” Pre-Post State Anxiety statements asked about participants’ immediate states of stress and anxiety with statements such as “I am tense”. Procedure One female and one male experimenter conducted four 60-minute small group sessions in a classroom setting. Participants were randomly assigned to the mindfulness experimental group or the audiobook control. The experimenter first described the study and obtained consent from participants. All participants completed the questionnaire and completed a short math quiz followed by the Pre-State Anxiety measure. After participants listened to a 10 minute CD (mindfulness or audiobook), they completed a second math quiz and the Post-State Anxiety measure. Finally, the experimenter provided a debriefing form, answered questions, and thanked the students for participating. Results It was hypothesized that a brief mindfulness exercise and whether or not participants had previously received counseling for anxiety would influence participants’ negative symptoms of anxiety. Specifically, participants who listened to the mindfulness exercise were expected to show a greater reduction in negative anxiety symptoms than participants who listened to the audiobook control. Furthermore, it was hypothesized that the effect of a brief mindfulness exercise would vary according to participants’ counseling history. These hypotheses were tested MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY 14 with a 2 (Mindfulness, Control) x 2 (Counseling, No counseling) x (Male, Female) independent samples ANOVA. The ANOVA showed that reduction in negative symptoms varied by gender and whether participants had received counseling for anxiety, F(1, 77) = 3.38, p = .07. Females who had previously received counseling for anxiety (M = 3.40, SD = 0.40) showed a greater reduction in negative anxiety symptoms than females who had no counseling history (M = 2.34, SD = 0.41). However, there was no difference in reduction for males (F < 1.0). Males who had received counseling (M = 2.99, SD = 0.33) and males who had not received counseling (M = 3.27, SD = 0.30) showed no difference in reduction of negative anxiety symptoms. In addition, there was no main effect of the mindfulness exercise on anxiety, F(1, 77) = 0.15, p = .70. Discussion Men and women differed in reduction of negative symptoms according to whether they had received counseling for anxiety. Women who had received counseling for anxiety in the past showed a larger reduction than women who had not; however, there was no difference in reduction for men who had received counseling and those that had not received counseling. The finding that women with previous counseling experience had a greater reduction in anxiety than women without counseling experience may be due to these women learning about attention and emotion regulation strategies and consequently responding better to the brief mindfulness exercise. It also could have been due to the fact that these women were less anxious about practicing mindfulness or less bothered by practicing in a large group setting. As for the men who showed no difference between those that had received counseling and those that had not, it is nearly impossible to say why we saw this effect. Future research should attempt to repeat this finding before any conclusions can be made. MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY 15 Although, past research shows that practicing mindfulness regularly can reduce stress and anxiety; the present research shows that a single 10-minute intervention does not produce noticeable reduction in state anxiety. This lack of difference between the mindfulness exercise and audiobook control leads the researchers to believe that listening to a single, 10-minute mindfulness exercise is simply not enough to produce significant reductions in anxiety. In fact, many participants became more anxious after listening to the mindfulness exercise, which may mean that the first exposure to mindfulness in a large group setting can be anxiety provoking for some people. General Discussion Past research has demonstrated beneficial effects of mindfulness in terms of reductions in stress and anxiety after several weeks of practice (Greeson, 2008), three 2-hour sessions, (Harnett et al., 2010), and five 20-minute sessions (Tang et al., 2007); however, no previous research has tested the effectiveness of a very brief mindfulness exercise. The current findings suggest that a single, 10-minute exposure to mindfulness may not be sufficient to produce significant reductions in state anxiety, and may even be anxiety provoking. The practice of mindfulness, the non-judgmental awareness of the present moment, takes considerable time and effort to cultivate (Kabat-Zinn, 2005). Practicing mindfulness is an active process that requires considerable effort and discipline in order to experience benefits. Participants in this study, in contrast, merely passively listened to very brief mindfulness exercise instructions and consequently, did not experience any anxiety reducing benefits. Lowered stress and anxiety, increased self-regulation abilities, and enhanced wellness can be seen through repeated practice over several months, weeks, or days. However, 10 minutes of passively listening to mindfulness produces no such benefits. Furthermore, after analyzing our findings, we must assess whether the MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY 16 first exposure to mindfulness might produce anxiety in some people. The findings from both studies support that the first exposure may increase anxiety for some individuals. Possible explanations are that the large-group setting or the words meditation and mindfulness may provoke judgmental and negative thoughts for some individuals, which consequently could increase anxiety. In general, individuals with high math anxiety became less anxious regardless of the mindfulness exercise, which may have produced a regression to the mean. These findings are consistent with past research such that individuals with math anxiety are more likely to have higher trait anxiety and score high on other anxiety tests (Ashcraft, 2002). Consequently, individuals with high math anxiety may be more sensitive to reduction in state anxiety. Also consistent with past research was the finding that math anxiety was more prevalent among women, who have higher rates of anxiety in general. It is interesting to speculate that woman may show greater reductions in anxiety due to mindfulness practice, but that was not explored in this first study. Math anxiety may be especially high in women due to the effects stereotype threat in which some women may fear that their performance on a math test will support the unfounded belief that women are worse at math than men (Akin & Kurbanoglu, 2011). In addition, the current findings suggest that participants who had a high capacity to regulate their attention and emotion (i.e., scored high on CAMS-R) were less likely to engage in suppressivestyle emotion regulation, which supports past research in that suppression undermines emotional stability. Interestingly, an fMRI study found that the brains of individuals with high math anxiety had increased activity in regions associated with physical pain when anticipating an approaching math test, but not when actually completing the math problems (Lyons & Beilock, 2012). For MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY 17 individuals with math anxiety, merely the expectation of doing math is painful. This may explain why math anxious individuals tended to become less anxious over time, even without listening to a mindfulness exercise. The growing evidence and prevalence of math anxiety begs the question as to whether teaching mindfulness in the classroom could potentially play a role in preventing the onset of math anxiety and promote self-regulation skills. Another important aspect to examine is the finding that pre-existing individual differences in mindfulness may influence the capacity to cope with anxiety. People who came into the study with high mindfulness tendencies showed no effect of math anxiety. Perhaps being better able to regulate attention and emotion makes people more immune to the effects of math anxiety. For example, some people may have a natural ability to focus their attention and emotion, which may help them deal with stress and anxiety better than those who do not have mindfulness tendencies. The applications of mindfulness are being explored in healthcare, where mindfulness is becoming increasingly integrated as a complimentary way for patients to take control of their mental and physical health. Mindfulness has the potential to teach children and teens selfregulation strategies in order to promote attention and emotional stability, which could potentially play a role in preventing math anxiety and attention deficit disorders. Finally, research on mindfulness may play a key role in exposing the physiological connection between the mind and body. Future research might investigate whether longer exposures to mindfulness practice reduces math anxiety, especially since eight weeks of mindfulness has been shown to reduce stress and anxiety and produce structural changes in the brain that are believed to improve self-regulation and reduce emotional reactivity (Hölzel et al., 2011). MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY 18 References Akin, A., & Kurbanoglu, I. N. (2011). The relationships between math anxiety, math attitudes, and self-efficacy: A structural equation model. Studia Psychologica, 53(3), 263-273. Ashcraft, M. H. (2002). Math anxiety: Personal, educational, and cognitive consequences. Current Directions In Psychological Science, 11(5), 181-185. Flugel Colle, K. F., Vincent, A., Cha, S. S., Loehrer, L. L., Bauer, B. A., Wahner-Roedler, D. L. (2010). Measurement of quality of life and participant experience with the mindfulnessbased stress reduction program. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 16, 3640. Greeson, J. M. (2009). Mindfulness research update: 2008. Complementary Health Practice Review, 14(1), 10-18. Gross, J. J. (1999). Emotion regulation: Past, present, future. Cognition And Emotion, 13(5), 551573. Harnett, P. H., Whittingham, K., Puhakka, E., Hodges, J., Spry, C., & Dob, R. (2010). The shortterm impact of a brief group-based mindfulness therapy program on depression and life satisfaction. Mindfulness, 1(3), 183-188. Hölzel, B. K., Lazar, S. W., Gard, T., Schuman-Olivier, Z., Vago, D. R., Ott, U. (2011). How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(6) Kabat-Zinn, J. (2005). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness: Fifteenth Anniversary Edition. New York, NY: Delta Trade Paperback/Bantam Dell. Kabat-Zinn, J. (2012). Mindfulness for Beginners. Sandstone MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY 19 Koole, S. L. (2010). The psychology of emotion regulation: An integrative review. In J. De Houwer, D. Hermans, J. De Houwer, D. Hermans (Eds.) , Cognition and emotion: Reviews of current research and theories (pp. 128-167). New York, NY US: Psychology Press. Lyons, I. M., & Beilock, S. L. (2012). When Math Hurts: Math Anxiety Predicts Pain Network Activation in Anticipation of Doing Math. PLOS ONE. Rosenzweig, S., Reibel, D. K., Greeson, J. M., Brainard, G. C., & Hojat, M. (2003). Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction lowers psychological distress in medical students. Teaching And Learning In Medicine, 15(2), 88-92. Tang, Y.-Y., Ma, Y., Wang, J., Fan, Y., Feng, S., Lu, Q., Yu, Q., Sui, D., Rothbart, M. K., Fan, M., & Posner, M. I. (2007). Short-term meditation training improves attention and selfregulation. PNAS Proceedings Of The National Academy Of Science, 104(43), 1715217156. Young, C., Wu, S., & Menon, V. (2012). The neurodevelopmental basis of math anxiety. Association for Psychological Science, 1(10), 1-10. MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY 20 Table 1 Mean Reduction in State Anxiety as a Function of Mindfulness Exercise and Math Anxiety __________________________________________________________________________ Mindfulness Exercise ______________________________________________________ Breathing Body Scan Control _________________________________________________________________________________ Math Anxiety Level M SD M SD M SD _________________________________________________________________________________ Low .07 .32 .28 .35 .10 .29 _________________________________________________________________________________ High .34 .30 .84 .24 .88 .35 _________________________________________________________________________________ MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY 21 Figure 2. Mean Reduction in State Anxiety as a function of pre-existing Mindfulness and Math Anxiety MINDFULNESS AND MATH ANXIETY Figure 3. Reduction in Negative Symptoms as a function of Gender and Counseling 22