Reflexive Statement: I was born into the sixth generation on a farm in

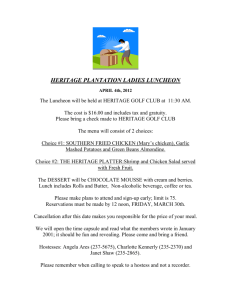

advertisement