Organic Farmers: Opportunities, Realities and Barriers

advertisement

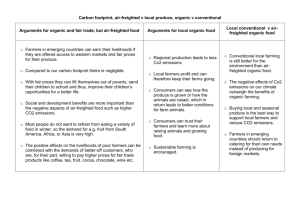

Organic Farmers: Opportunities, Realities and Barriers Dr. Leslie A. Duram Department of Geography and Environmental Resources Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL 62901 duram@siu.edu, 618.536-3375 This paper is organized in four sections. First, the interface between geography and agriculture will be described; second, an overview of the current research literature on organic agriculture will be presented; third, research from my book, Good Growing: Why Organic Farming Works (2005) will be described in detail; and finally, I will draw some general conclusions about the realities of adopting organic agricultural techniques. Geography and Agriculture The discipline of Geography is commonly misunderstood to include only simple facts, such as: “What is the capitol of Zimbabwe?” But, in fact, Geography includes much more, as indicated by the roots of the word: GEO is EARTH and GRAPHY is TO DESCRIBE. So, geographers describe the Earth through various means, including maps, data collection and analysis, descriptive texts about landscapes, and in-depth spatial analysis through Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Overall, geography deals with space and place; the interaction between humans and the environment; and linkages between and among places. Because of this comprehensive approach to research and concern for environmental sustainability, Geography is particularly successful in the study of agricultural topics. Within the broader concept of sustainable agriculture, one specifically defined methods is certified organic farming. Data on U.S. organic agriculture is limited, as it was only recently included in the US Census of Agriculture. Thus most data is based on research surveys and informed estimates. For example, it is estimated that 1-7% of farmers use organic methods. In Draft Session Paper – Organic Agriculture Workshop, USDA, ERS, October 6-7, 2005 Final Papers to be Published by Crop Management, Summer, 2006 1 fact, certified organic cropland doubled in the 1990s and there are currently 2.34 million acres of certified organic farmland in this country. Interestingly, there are significant variations among crop types. Only 0.1% of corn and soybeans are certified organic, while 2% of specialty crops such as lettuce, carrots, apples, and grapes are grown organically. Some specialty crops have much higher levels of organic production, for example 30% of buckwheat and 37% of spelt are certified organic crops (USDA-ERS 2001, 2002, and 2003). Background Research Previous research literature on organic agriculture may be best understood in two main categories: Organic Production and Organic People. First, in terms of production research, studies have focused on economics, production comparisons, and landscapes. Second, in terms of people and society, organic research has addressed organic farmers, consumers of organic products, and issues related to local food systems. Research into comparisons between organic and conventional agricultural production indicates that, in terms of profit, organic farming can be quite rewarding. Put simply, lower input costs combined with price premiums, lead to higher profit margins (Smolik and Dobbs 1991, Batte et al. 1993). In a recent study conducted in the Corn Belt, organic methods yielded the higher net returns than conventional production in 5 of 6 years (Illinois Stewardship Alliance 2002). In fruit and vegetable production, researchers found that organic methods led to similar pest losses with significantly better tasting produce (Reganold et al. 2001; Letourneau & Goldstein 2001). Keep in mind that production comparisons are very complex. Are test plots or field experiments conducted on university farms really comparable with long-term land management Draft Session Paper – Organic Agriculture Workshop, USDA, ERS, October 6-7, 2005 Final Papers to be Published by Crop Management, Summer, 2006 2 variables found on actual organic farms? Do researchers miss important on-farm management variables when we conduct such university research? How do we accurately “match” conventional and organic fields when we conduct comparisons? Research results show that in 30 cases of comparative observations of on-farm productivity, organic yields were higher than conventional yields in 13 cases, were equal in 2 cases, and were lower in 15 cases, but this variability was less than 20%. Overall, organic productivity is more reliable and higher yielding in variable growing conditions, particularly drought (Pimentel et al., 2005, Mäder et al 2002, Clark et al. 1999, Hanson et al. 1997, Stanhill 1990, Lockeretz et al., 1981). Research investigating landscape assessment has been conducted in the European Union. Through the EU’s Production Research Policy for Rural Sustainability, an assessment framework draws from four categories: ecology, economy, social factors, and cultural geography. Studies in several countries indicate that organic farms provide higher scores on these landscape variables (Agriculture Ecosystem & Environment 2000). Other ecological research indicates that soil quality is better on organically farmed land. In terms of topsoil depth, soil structure, porosity, and other variables, organic methods lead to improved soil quality (Liebig and Doran 1998, Shepherd et al. 2002 ). Finally, biodiversity, as measured by bird and insect species, is greater on organic farms than on conventional farms (Shutler et al. 2000, Blackburn & Arthur 2001). Research into social issues related to organic farming begins with the farmers themselves. Demographic characteristics show high variability, but in general, organic farmers tend to be younger, have a higher level of formal education, and are more likely female, when compared to conventional farmers (Lockeretz 1995, Egri 1999, Duram 2000). Many organic farmers maintain a worldview that is distinct from their conventional counterparts. They have Draft Session Paper – Organic Agriculture Workshop, USDA, ERS, October 6-7, 2005 Final Papers to be Published by Crop Management, Summer, 2006 3 heightened ecological awareness, seek more alternatives, and are more independent (Beus and Dunlap 1990, 1994, Duram 1997). Another key social factor is organic consumers. Who buys organic food? This question has never been fully answered, but there are a few key ideas to keep in mind. First, the organic products market is growing at a phenomenal rate: 20% annually by many accounts; it was approximately $9.3 billion in 2004. When ABC News conducted a poll in 2001, over half of all U.S. consumers said that they prefer organic produce. Both the domestic and export market are important for American farmers. USDA-ERS 2002; ABC NEWS 2001; Natural Foods Merchandiser 2002). Along with consumer demand for organic food generally, there is growing interest in local organic food production and sales. Researchers have studied this issue and developed a few interesting terms. First, a “food mile” is how far any food travels from farm to table—and this is a staggering 1,800 miles, on average, in the US today. Many consumers what to reduce food miles and eat locally produced foods. Second, a related concept is that of a “foodshed” which, like a watershed, indicates that all food is produced and flows to consumers within one region. In order to meet these increasing demands for local food, farmers are turning to alternative means of marketing and sales. Farmers’ markets have been booming in the US and continue to grow in number and popularity. Likewise Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) is also increasing; this is a relationship in which consumer members buy “shares” to a farm which then supplies them with produce throughout the growing season. Both farmers’ markets and CSAs are making an important impact on organic farmers ability to connect with local consumers. Draft Session Paper – Organic Agriculture Workshop, USDA, ERS, October 6-7, 2005 Final Papers to be Published by Crop Management, Summer, 2006 4 Current Research: Good Growing Based on extensive research conducted for the book Good Growing: Why Organic Farming Works, this paper presents an analysis of the following research question: What are the main opportunities and barriers for organic farmers? This research employed a mixed methods analysis, through which five case study farms were studied to represent a broad distribution across U.S. agriculture. Organic farms in California, Colorado, Florida, Illinois, and New York were used as case studies of both production and social concerns related to organic production. These farms, or specifically the farmers, are each very special and unique, as the California farmer is an expert at marketing organic vegetables at the regional scale; this Colorado farm family has been producing grains on the land for five generations; the Florida growers are very proud of the high quality of their citrus crops; in Illinois we see an example of a highly diversified farm that is truly unique in the Corn Belt region; and in upstate New York, the farmer developed a huge CSA within an ever-changing operation that included livestock, feed grains and organic vegetables. On-farm visits and extensive interviewing was key to this research. This analysis was based on a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods. Qualitative methods include: recording, transcribing, and coding themes from the interviews. This coding allowed for crosscase comparisons, through which generalizations were discovered (Agar 1980, Abbott 1992, Miles & Huberman 1994, Duram 2000). Quantitative data was also gathered and appropriate univariate statistics were employed. This was contingent upon available data, of course. Draft Session Paper – Organic Agriculture Workshop, USDA, ERS, October 6-7, 2005 Final Papers to be Published by Crop Management, Summer, 2006 5 First, we notice variations in the ecological conditions of each farms’ location (Figure 1). The drier conditions of the California and Colorado farms contrast sharply to the higher precipitation of the other three locations. Such variations are expected in these types of ecoregions, of course, as are the temperature variations. General soils types are also important to each production scheme. Second, there are important on-farm factors that influence each farmer. The farm size of each case study farm is smaller than the average conventional farm sizes in each region. The year of each farm’s initial certification shows substantial experience and time commitment to organic production. These farmers are experienced with local, regional, national, and even international marketing efforts. The fruit, vegetables, grains, legumes, and livestock grown by these five farmers represents nearly all the crops produced in the US! Indeed these farmers are highly diversified and, in fact, see diversification as key to their livelihood. According to these five case study farmers, the key factors that influence opportunities and barriers to organic production are: economics, ecology, society, and personal variables. Through analysis of interviews and extensive review of many visits, emails and telephone conversations, these factors I discovered additional sub-categories that are common among these and many organic farmers across the US. For the economic category, farmers indicate that marketing is a central concern for their farm’s survival. Marketing factors include the need for diversification, the importance of direct marketing, and the newest concerns about how to withstand the powers of organic agri-business. Also in terms of economic concerns, the farmers firmly believe that crop types and quality are very important for their success. Finally, these farmers indicate that organic agriculture provided an opportunity for them—they say they could Draft Session Paper – Organic Agriculture Workshop, USDA, ERS, October 6-7, 2005 Final Papers to be Published by Crop Management, Summer, 2006 6 not have succeeded in conventional agriculture today with the low commodity prices and lack of freedom from agri-business. In terms of ecology, organic farmers commonly discussed soil health, ecosystems, and balance. They may or may not use scientific terms for these concepts, but they clearly understand the ecological processes at work on their farms. They also describe the annual gamble with weather and growing conditions; they realize they cannot control these factors, but rather must mediate them to the best of their ability. Social issues play an important role in the success of organic farming. These farmers had very clear visions of how American culture impacts agriculture and specifically how culture and politics support the conventional production system with extensive subsidies. They see how many consumers simply want cheap food, often at the long-term expense of the environment and rural communities. Organic farmers have very specific recommendations for policies that would improve opportunities for organic production. First, the US government must do more than simply implement national certification standards, rather they must support farmers through the difficult 3 year transition period. The government should also provide greater research, information, and educational support for organic production techniques. The personal characteristics were broadly similar among this highly diverse group of 5 farmers and their farms. All five are fiercely independent and willing to accept risk at a personal level. That is, they are not afraid to be different from their neighbors, but they are only willing to operate with low debts. Their risk is in their unique methods, crops, and markets (not in their bank accounts). These organic farmers are highly innovative and conduct their own on-farm experiments because they have questions about organic farming methods that university researchers simply have not addressed. Draft Session Paper – Organic Agriculture Workshop, USDA, ERS, October 6-7, 2005 Final Papers to be Published by Crop Management, Summer, 2006 7 Finally, an important unifying characteristic is that these five case study farmers proudly represent the farming tradition, handed down from generations or from fellow organic farmers. Each describes the importance of their continuing to farm organically, as part of that tradition. Conclusion This research indicates that currently there are both opportunities and barriers to organic agricultural production in the US. In fact, the line between opportunity and barrier can be bleary; for example, organic farmers are greatly motivated by being independent—organic production provides a great opportunity, but it is also a barrier because they have less outside support in organic methods of production. In addition, the popularity of organic products in both an opportunity (increased marketing options) but a barrier, as agri-business corporations are now making inroads into marketing which will subvert some farmers’ levels of independence. Likewise, their farming tradition is sometimes a barrier, if it makes farmers more closed-minded about alternative methods like organic. But of course tradition is a key asset if it provides entry into the farm business and access to land. Diversification provides a key opportunity to spreading out the risk for organic farmers, but it can also be a barrier, as the extensive marketing work increases with each additional crop produced. Overall, then, there are both opportunities and barriers that organic farmers must face. Two key factors would help them sustain their operations, and may help others adopt organic methods well into the future. Organic farmers need research and information, they need to be informed so that they can make good choices for their production and marketing activities. In addition, the three year transition to certified organic production is challenging. During this Draft Session Paper – Organic Agriculture Workshop, USDA, ERS, October 6-7, 2005 Final Papers to be Published by Crop Management, Summer, 2006 8 time, farm fields are undergoing tremendous change as synthetic chemicals are withdrawn. Farmers have a huge learning curve to get up to speed on organic methods, and farmers do not receive a price premium for their crops during this transition period. Indeed, the transition to certified organic methods is a crucial time, and can sometimes mean the difference between adopting organic methods successfully or failing. Again, research and information advice is important at this stage, but financial assistance would be extremely useful. Government programs to support farmers in their three year transition would make an important statement as to public commitment to the benefits of organic agriculture. Farmers must face major barriers in organic production; American society and government should assist whenever possible in lower those barriers and indeed creating opportunities for organic farming to flourish. Draft Session Paper – Organic Agriculture Workshop, USDA, ERS, October 6-7, 2005 Final Papers to be Published by Crop Management, Summer, 2006 9 References ABCNews.com. 2001. Poll: Behind the Label: Many Skeptical of Bio-Engineered Food, Organic Advantage. June 19, 2001. Accessed 1/6/04 at: http://abcnews.go.com/sections/scitech/DailyNews/poll010619.html Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment. 2000. Volume 77, Issues 1-2. Batte, Marvin T., D. Lynn Foster, and Fred J. Hitzhusen. 1993. Organic Agriculture in Ohio: An Economic Perspective. Journal of Production Agriculture 6(4):465-542. Beus, Curtis E. and Riley E. Dunlop. 1994. Agricultural Paradigms and the Practice of Agriculture. Rural Sociology 59(4):620-635. Beus, Curtis E. and Riley E. Dunlop. 1990. Conventional Versus Alternative Agriculture: The Paradigmatic Roots of the Debate. Rural Sociology 55(4):590-616. Blackburn, James and Wallace Arthur. 2001. Comparative Abundance of Centipedes on Organic and Conventional Farms, and its Possible Relation to Declines in Farmland Bird Populations. Basic And Applied Ecology 2(4):373-381. Brown, Allison. 2002. Farmers’ Market Research 1940-2000: An Inventory and Review. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture 17(4):167-176. Clark, Sean, Karen Klonsky, Peter Livingston, and Steven Temple. 1999. Crop-Yield and Economic Comparisons of Organic, Low-input, and Conventional Farming Systems in California’s Sacramento Valley. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture 14(3):109-121. Cone, Cynthia Abbott, and Andrea Myhre. 2000. Community-Supported Agriculture: A Sustainable Alternative to Industrial Agriculture? Human Organization 59(2):187-197. DeLind, Laura B. 1998. Close Encounters with a CSA: The Reflections of a Bruised and Somewhat Wiser Anthropologist. Agriculture and Human Values 16:3-9. Duram, Leslie A. 1997. A Pragmatic Study of Conventional and Alternative Farmers in Colorado. Professional Geographer 49(2):202-213. Duram, Leslie A. 2000. Agent’s Perceptions of Structure: How Illinois Organic Farmers View Political, Economic, Social, and Ecological Factors. Agriculture and Human Values 17:35-48. Duram, L. 2005. Good Growing: Why Organic Farming Works. University of Nebraska Press. Duram, Leslie A. and Kelli L. Larson. 2001. Agricultural Research and Alternative Farmers’ Information Needs. Professional Geographer 53(1):84-96. Draft Session Paper – Organic Agriculture Workshop, USDA, ERS, October 6-7, 2005 Final Papers to be Published by Crop Management, Summer, 2006 10 Egri, Carolyn. 1999. Attitudes, Backgrounds and Information Preferences of Canadian Organic and Conventional Farmers: Implications for Organic Farming Advocacy and Extension. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 13(3):45-72. Hanson, James, Erik Lichtenberg, and Steven Peters. 1997. Organic Versus Conventional Grain Production in the Mid-Atlantic: An Economic and Farming System Overview. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture 12(1):2-9. Hyvönen, Terho, E. Ketoja, J. Salonen, H. Jalli, and J. Tiainen. 2003. Weed Species Diversity and Community Composition in Organic and Conventional Cropping of Spring Cereals. Agriculture Ecosystems and Environment 97 (1-3): 131-149. Illinois Stewardship Alliance. 2002. Stewardship Farm: Final Report on the Farming Systems Comparison Study: Comparing the Economics of Conventional, No Till, Organic, and Three Crop Farming Systems. Rochester, Illinois. Kloppenburg, Jack Jr., John Hendrickson, and G.W. Stevenson. 1996. Coming in to the Foodshed. Agriculture and Human Values 13:33-42. Letourneau, D.K., and B. Goldstein. 2001. Pest Damage and Arthropod Community Structure in Organic vs. Conventional Tomato Production in California. Journal of Applied Ecology 38:557570. Liebig, Mark and J. Doran. 1998. Impact of Organic Production Practices on Soil Quality Indicators for Select Farms in Nebraska and North Dakota. USDA: Agricultural research Service.1998-06-11. Accessed 1/6/04 at: http://warp.nal.usda.gov:80/ttic/tektran/data/000009/23/0000092349.html. Lockeretz, William. 1995. Organic Farming in Massachusetts: An Alternative Approach to Agriculture in an Urbanized State. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 50(6):663-667. Lockeretz, William, Georgia Shearer, And Daniel H. Kohl. 1981. Organic Farming in the Corn Belt. Science 211:540-547. Mäder, Paul, Andreas Flieβbach, David Dubois, Lucie Gunst, Padrout Fried, and Urs Niggli. 2002. Soil Fertility and Biodiversity in Organic Farming. Science 296:1694-1697. Natural Foods Merchandiser. 2002. News, Trends and Ideas for the Business of Natural Products. June. 82pp. Norberg-Hodge, Helena. 1995. From Catastrophe to Community. Resurgence 171:12-14. Pimentel, D., P. Hepperly, J. Hanson, D. Douds, and R. Seidel. 2005. Environmental, Energetic, and Economic Comparisons or Organic and Conventional Farming Systems. BioScience 55:7:573-582. Draft Session Paper – Organic Agriculture Workshop, USDA, ERS, October 6-7, 2005 Final Papers to be Published by Crop Management, Summer, 2006 11 Reganold, John P., Jerry D Glover, Preston K Andrews, and Herbert R Hinman. 2001. Sustainability of Three Apple Production Systems. Nature 410:926-930. Shepherd, M.A., R. Harrison, and J. Webb. 2002. Managing Soil Organic Matter- Implications for Soil Structure on Organic Farms. Soil Use and Management 18(3):284-292. Shutler, Dave, Adele Mullie, and Robert G. Clark. 2000. Bird Communities of Prairie Uplands and Wetlands in Relation to Farming Practices in Saskatchewan. Conservation Biology 14(5):1441-1451. Smolik, James and Thomas Dobbs. 1991. Crop Yields and Economic Returns Accompanying the Transition to Alternative Farming Systems. Journal of Production Agriculture 4(2):153-161. Stanhill, G. 1990. The Comparative Productivity of Organic Agriculture. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 30:1-26. USDA-AMS. 2002. Farmers Market Facts! United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service. Accessed: 1/6/04 at: http://www.ams.usda.gov/farmersmarkets/facts.htm. USDA-ERS. 2001. U.S. Organic Farming Emerges in the 1990’s: Adoption of Certified Systems. USDA, Economic Research Service, Resource Economics Division. Agriculture Information Bulletin No. 770. Greene, Catherine. USDA-ERS. 2002. Recent Growth Patterns in the U.S. Organic Foods Market. USDA, Economic Research Service, Agriculture Information Bulletin Number 777. Dimitri, Carolyn and Catherine Greene. USDA-ERS. 2003. U.S. Organic Farming in 2000-2002: Adoption of Certified Systems. USDA, Economic Research Service, Agriculture Information Bulletin, No. 780. Greene, Catherine, and Amy Kremen. Draft Session Paper – Organic Agriculture Workshop, USDA, ERS, October 6-7, 2005 Final Papers to be Published by Crop Management, Summer, 2006 12 FIGURE 1: Ecological Factors on Case Study Farms CA CO FL IL Ecoregion California West High Coastal Prairie Coastal Plains Plain Parkland Chaparral Forest Temperate Precipitation 14.7” 15.2” 49.8” 36.7” Soil Type Clay loam Loam Fine sand Silt loam Drainage Moderate Well Excessive Moderate Jan./July 38-83°F 12-90°F 46-92°F 9-83°F Low/High NY Great Lakes Mix Forest 35.9” Silt loam Well 16-82°F Draft Session Paper – Organic Agriculture Workshop, USDA, ERS, October 6-7, 2005 Final Papers to be Published by Crop Management, Summer, 2006 13 FIGURE 2: Case Study Farm Characteristics. CA CO FL Acres 250 4,800 14 Year Markets 1989 Regional Crops 30 vegetables, nuts, fruits 1977 1992 Natl & National International wheat, 11 citrus buckwheat, varieties millet,corn, alfalfa IL 300 NY 500 1994 Local & National chicken, turkey, beef, soy, sorghum flax, millet, 1990 Local CSA & Regional 25 vegetables sheep, soy, corn, barley, hay Draft Session Paper – Organic Agriculture Workshop, USDA, ERS, October 6-7, 2005 Final Papers to be Published by Crop Management, Summer, 2006 14