Abstract

advertisement

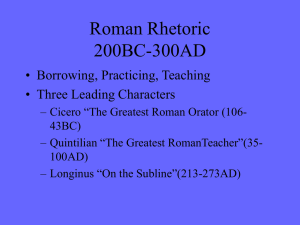

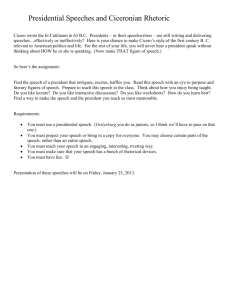

Cicero between the res publica and the cosmopolis: a tension in Roman political philosophy Despite how Cicero himself may have conceived of his philosophical efforts, the beginning of Cicero’s philosophical career marked the end of his political one. By 56, the consolidation of the extra-constitutional alliance of Caesar, Pompey and Crassus had rendered Cicero politically impotent. His effective retirement from public life and the burst of philosophical writings which followed, however, do represent (along with Lucretius’ De rerum natura) the birth of Roman political philosophy, a tradition inestimably indebted, of course, to the Greeks. Nevertheless, Cicero’s choice of Latin and his selection of Roman characters, contexts and exempla marked his philosophical works with a distinctly Roman novelty, and his first philosophical treatise, De re publica, composed between 54 and 51, from its very title is thoroughly Roman (See Griffin 1991, Morford 2002, Reydams-Schils 2005). However, characterizing Roman political philosophy from its very inception is a particular tension between the demands of political responsibility at home and the need for a more panoramic, universal vision through which one might better glimpse humanity’s place in the cosmos—what might be characterized in other words as a Romanized encounter with the philosophical problematic between the political and contemplative life, that is, between the res publica and the cosmopolis. In order to better characterize this tension, I aim first to point to particular exemplifying passages in Cicero’s De re publica, where this problem is first encountered. Of particular interest are the extant portion of Cicero’s prologue to book I, wherein he identifies reasons for entering public life and criticizes the appealing Epicurean turn to the quiet life; Scipio’s definition of the res publica, whose foundations are in human nature, also in book I; Laelius’s speech on justice and law in book III; and the elder Scipio’s description of the universe and exhortations for patriotism in book VI. Second, I argue that such a commitment to both res publica and cosmopolis represents a severe discordance for ethico-political activity, whose consequences lead to the disintegration of personal integrity and thus the impossibility of politics as such. Lastly, I seek out the resources of Cicero’s final philosophical treatise, De officiis, in which Cicero’s appropriation of Panaetian personae theory offers a possible resolution to this dangerous problematic by assigning these divergent commitments among the four divisions of personae (See Gill 1988, Reydams-Schils 2005). To conclude, I shall very broadly gesture at residual elements of this problematic still present in Roman philosophy as late as Marcus Aurelius. Bibliography Gill, Christopher. 1988. “Personhood and personality: the four-personae theory in Cicero, De officiis I.” Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy. Vol. 6. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 16999. Griffin, M. T. and E. M. Atkins., trans. 1991. Cicero: On Duties. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. Morford, Mark. 2002. The Roman Philosophers: from the time of Cato the Censor to the death of Marcus Aurelius. New York: Routledge. Powell, J. G. F., ed. 2006. M. Tulli Ciceronis: De re publica, De legibus, Cato Maior de senectute, Laelius de amicitia. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. Rudd, Niall, trans. 1998. Cicero: The Republic and The Laws. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. Winterbottom. M., ed. 1994. M. Tulli Ciceronis: De officiis. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. Reydams-Schils, Gretchen. 2005. The Roman Stoics: self, responsibility, and affection. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press. Zetzel, James E. 1995. Cicero: De re publica Selections. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.