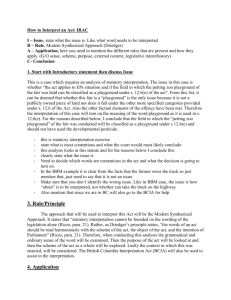

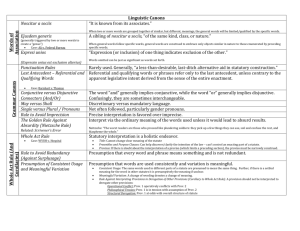

Statutory Interpretation - LSA - AED

advertisement