- UVic LSS

advertisement

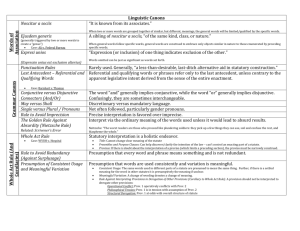

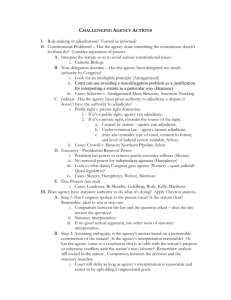

How to Interpret an Act: IRAC I – Issue, state what the issue is. Like what word needs to be interpreted R – Rule, Modern Synthesized Approach (Driedger) A – Application, here you need to mention the different rules that are present and how they apply. (G/O sense, scheme, purpose, external context, legislative intent/history) C- Conclusion 1. Start with Introductory statement then discuss Issue This is a case which requires an analysis of statutory interpretation. The issue in this case is whether “the act applies to EPs situation and if the field in which the petting zoo playground of the fair was held can be classified as a playground under s. 12.6(e) of the act”. From this list, it can be deemed that whether this fair is a “playground” is the only issue because it is not a publicly owned piece of land nor does it fall under the other more specified categories provided under s. 12.6 of the Act. Also the other factual elements of the offence have been met. Therefore the interpretation of this case will turn on the meaning of the word playground as it is used in s. 12.6(e). For the reasons described below, I conclude that the field in which the “petting zoo playground” of the fair was conducted will be classified as a playground under s 12.6(e) and should not have used the developmental pesticide. - this is statutory interpretation exercise state what is most contentious and what the court would most likely conclude this analysis looks at this statute and for the reasons below I conclude this clearly state what the issue is Need to decide which words are contentious in the act and what the decision is going to turn on. In the BBM example it is clear from the facts that the farmer owns the truck so just mention that, just need to say that it is not an issue. Make sure that you don’t identify the wrong issue. Like in BBM case, the issue is how “about” is to be interpreted, not whether can take the truck on the highway Also mention that since we are in BC will also go to the BCIA for help 3. Rule/Principle The approach that will be used to interpret this Act will be the Modern Synthesized Approach. It states that “statutory interpretation cannot be founded on the wording of the legislation alone (Rizzo, para. 21). Rather, as Driedger’s principle states, “the words of an act should be read harmoniously with the scheme of the act, the object of the act, and the intention of Parliament” (Rizzo, para. 21). Therefore, when conducting this analysis the grammatical and ordinary sense of the word will be examined. Then the purpose of the act will be looked at and then the scheme of the act as a whole will be explored. Lastly the context in which this was enacted, will be considered. The British Columbia Interpretation Act (BCIA) will also be used to assist in the interpretation. 4. Application Grammatical and Ordinary Sense: - Before we conduct the grammatical and ordinary sense analysis, we must first go to the act and BCIA to see if the word is defined there. If it is, then there is no need to conduct this analysis. However, “” is not defined in either the Act or the BCIA and so we can proceed with the analysis. - Dictionary o Shaklee: in absence of statutory definition, can use dictionary definition. But sometimes dictionary definitions are so broad that you need to consider what the ordinary person understands that word as meaning. o Dictionary definitions may not always be determinative therefore it is necessary to examine other factors that can determine how a word is to be defined. (Riddell) - Ordinary Person o “what would the reasonable person of average intelligence and understanding take to be the usual meaning of the words?” (Shaklee) o Sharpe: you read a word from the perspective of the reasonable person. - Plain meaning o McIntosh: the idea that the words should be read as they are written - Plausible meaning - Ordinary meaning Purpose - Purpose must also be established by looking at the context. Legislative intent can be declared or implied. - Components of the Act: Purpose statement, preamble, title is enacted with the Act, so can show purpose also can use preamble, they assist (s.9) - Section 8: this says that the interpretation must be remedial. This means that “every enactment is deemed remedial, and shall be given such fair, large and liberal construction and interpretation as best ensures the attainment of is objects.” So interpret so that it fulfills the legislative purpose the best - Presumptions about the area (tax, human rights) – they can go elsewhere o Human Rights: Shouldn’t have strict interpretation of human rights legislation, you have to be broad and the focus must be on human rights. Jubran: Have to let it apply because a narrow reading on the section is inconsistent with the directions of the Supreme Court of Canada that human rights legislation be given a broad interpretation that will advance its purposes and objects and that the “strict grammatical approach” is inappropriate. o Taxation Statutes: Due to the complexities of polices and principles embodied in taxation statutes, the court is reticent when faced with the task of interpretation. The court will refrain from judicial innovation except in the case of explicit authority by Parliament. Ludco: When interpreting the Income Tax Act courts must be mindful of their role as distinct from that of Parliament. In the absence of clear statutory language, judicial innovation is undesirable. - - Imperial Oil: The particularity of tax provisions have often led to an emphasis on textual interpretation. o Municipal Law: United Taxi Drivers – a broad purposive approach to the interpretation of municipal legislation is also consistent with this Court’s approach to statutory interpretation generally. o Professional Bodies: gradual shift away from the strict interpretation Charter Values (this act has this purpose and should conform to these values) o Presumption that legislature does not intend to adversely affect individual rights, that where there are two reasonable interpretations, the court should select the one which does the least harm to the individual rights, or presumption that legislation which affects individuals rights should be given strict construction o Bell ExpressVu: The courts did not look too kindly on government interference on individual property rights. This then grew to apply to other rights in general Only should consult the Charter when situations of ambiguity arise. If the courts were to interpret all statutes such that they conformed to the Charter, this would wrongly upset the balance between the three levels. o Therefore when a statute is unambiguous, the courts must give effect to the clearly expressed legislative intent and avoid using the Charter to achieve a different result. o Go to presumption of individual rights, only when ambiguous, last resort. Only after you have conduct the modern synthesized approach and it is still ambiguous. Benefit conferring legislation: parliament wouldn’t make legislation to be beneficial to someone if it’s interpreted in a way that’s not beneficial to them (Merk, Rizzo). Scheme: Other provisions in statute, subsections - When examining scheme of the act one has to examine all the other sections of the act which relate to the section in question. - Look to see if there are definitions in the statute - Binlinguality: Canada 3000 - one language is broader, go for restricted one. For bilingual legislation shared meaning must be taken - Latin Maxims o Principle of Associated Meaning: a word takes its meaning from the surrounding words. McDiarmid Lumber: In this case it was said that it makes sense in the context of the act for the interpretation of the word agreement to be formed by treaty. o Presumption Against Tautology (Rule of Effectivity): All the words in an enactment are put there for a specific purpose and accordingly one should not adopt an interpretation of a provision that has the effect of rendering any of the words in any section “redundant” or “mere surplussage”. McDiarmid: if agreement was interpreted to cover all type of agreements between governments and Indians, then the word treaty would have no role to play. Therefore, agreement must be read more narrowly as supplementing treaty. “Or” must also be considered because it is there for a reason o Ejusdem Generis Principle: Provides that a general phrase (blanket clause) will take its meaning from the specific words that precede it. The inevitable result being that the general phrase will be narrowed. Nanaimo (City): the pile of dirt - - didn’t fall under the basket clause because the municipality didn’t intend to include almost everything as being a nuisance. o Expressio Unius: Express meaning of one thing excludes all others by necessary implication. The potential scope is immense, and therefore the courts have said that this is a dangerous principle and should be used with great caution. Children’s Aid Society: no indication that silence is meant no responsibility o Uniformity of Expression: Schwartz v. Canada - Words used by Parliament are deemed to have the same meaning throughout the statute. This presumption was rebutted in Sharpe, where the word person was given different interpretations in different parts of the statute. Section 12, BCIA Marginal notes and headings o Headings: S. 11 of BCIA says inserted for convenience not interpretation. In the federal, Lohnes says that they are intrinsic aids in interpreting. o Marginal notes: In BC they are not used, Basaraba says they ought not to be relied upon in interpreting a statue. In the IA, s. 14 says that they form no part of the enactment and are only there for convenience. Wigglesworth says that they are not an integral part of the Charter Punctuation/schedules o Punctuation is a weak tool and may not always be used (Jaagusta and Popoff) o Schedules are clearly part of a statue and may be used for interpretation purposes. If a conflict with the body of a text, the body prevails. They are at the end of an enactment. External Context - Other Factors: Going beyond the statute and looking at legal precedents/common law interpretations o Horizontal Coherence: The idea that we assume a legislature to speak in one voice and therefore the interpretation of one statue may be aided by looking at any other enactment of the same legislature Columbia River v. BC: It is a fundamental principle of statutory interpretation that one can look to other statutes in pari material (relating to the same subject) for guidance (pg. 4-57). R. v. Ulybel Enterprises Ltd: “Principle of interpretation presumes harmony, coherence, and consistency between statutes dealing with the same subject matter” (para 52) Bell ExpressVu: Context plays an important role when a court construes the written words of a statute. Also quotes Ulybel As a general rule, courts are under an obligation to make all possible efforts to avoid a finding of inconsistency. A later enactment will prevail over an earlier one, a specific enactment will prevail over a general enactment and earlier more specific enactment will prevail over a later, general enactment. Levis (City) o Vertical Coherence: Is a legal requirement that provision of an enactment must conform to “higher level” enactments. In the event of a conflict, higher level enactments prevail and lower level enactments are non-operative. o o o o o All legislation must be consistent with the Constitution Subordinate Legislation must be consistent with their enabling statute Federal is paramount over provincial Where human rights conflicts with general, the former is paramount Commonwealth of Canada: should also not interpret legislation that is open to more than one interpretation as so to make it inconsistent with the Charter and hence of no force and effect” (para 37). R. v. Sharpe: “If legislation can be read in a way that is both constitutional and not, the former reading should be adopted Bell ExpressVu: “to the extent to which this Court has recognized a Charter values interpretive principle, such principle can only receive application in circumstances of genuine ambiguity, ie. where the statutory provision is subject to differing but equally plausible interpretations (466).” Blanket presumption of Charter consistency could sometimes frustrate true legislative intent, contrary to what is mandated by the preferred approach to statutory construction. International Instruments: should have coherence between Canadian Legislation and International Agreements. Baker: external treaties can be powerful even when they are not domesticated. In this case those conventions recognized the importance of being attentative to the rights and bests interests of children Public policy: consequences on society – parliament wanted certain effects on society, interpret the act to bring about these consequences. Rizzo: union concerns, Canada 3000: could take over other planes Consequentialist analysis Avoiding absurd or anomalous results (more general absurd results). Irrational when the outcome in which people deserving better treatment receive worse treatment. (Sullivan quote – Merk case) Parliament doesn’t intend absurd results in their legislation, Canada 3000, Rizzo, Merk Temporal Application/vested rights These are the common law presumptions, so should be external to the act The Presumption Against Retroactivity and the Presumption Against Interference with “Vested Rights” The presumption relating to Territorial Application: A legislature is presumed to enact a statute only in relation to persons, property, things or events that fall within the territorial boundaries of its legislative jurisdiction. Extrinsic aids: materials from which you glean the social context Judges take judicial notice of this Judicial Decisions like precedent, authority, date of the case, jurisdiction, court level and so on influence Administrative Interpretations: Decisions of administrative tribunals and interpretations by civil servants and ministers - - - Texts: Textbooks, scholarly treaties, and other legal literature are now clearly admissible for interpretative guidance. They are not binding, but may carry substantial weight if their source is widely recognized as an expert in the relevant field. General History o What was going on in society that that led to this act o What was happening in the society at the time, factual context. o The judge may at times take judicial notice of facts that are known to be related to the mischief that the statute was intended to remedy. Legislative Evolution o Any other acts before this that dealt with the matter o Other predecessors, Re-enactments from predecessors o What the previous versions of the same statute said. This can help determine if the change was done for substantive changes in law, or whether it was merely housekeeping. (section 37(2) cautions not to assume that changes are substantive) o Re Simon Fraser: Historical evolution shows that the disposal of certain words is relevant. Since you have an old provision taken out in the new version, you have to assume that the legislature intended to remove it. o S. 37 says no implications from repeal or amendment, etc. This was aimed at the mischief that minor changes in law were seen as being substantial. It is to avoid minor changes being given big effects. Legislative history o The current statutes history – how it came into being (amendments, social circumstances surrounding enactment o The specific history of that statute. The weight attached to this will vary. The following possible documents may be used, in descending order of weight o Briefing notes o Alternative draft versions of the statute o House committee reports o Hansard, arguments made with regards to this act. But NOT determinative – can be political (Sharpe, Rizzo) o Press Releases o Firearms Act: Issue was whether the parliament had the legislative authority to enact certain legislation. They say to determine purpose, can look at the context for Parliamentary history. They go to the Hansard and use the Minister’s speech to help interpret the purpose of the legislation

![R (Evans) and another v Attorney General [2015] UKSC 21](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006598240_1-a7706c52e14434f0fee64b71e28c9736-300x300.png)