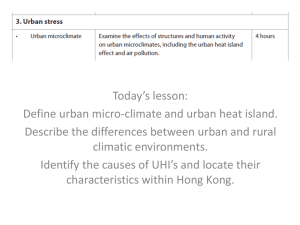

Education Reforms in Hong Kong: Challenges, Strategies

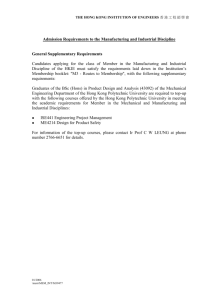

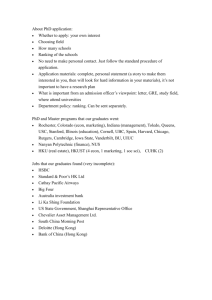

advertisement