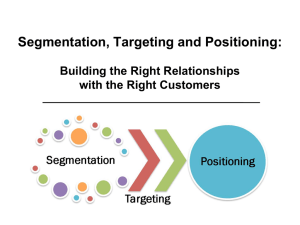

Chapter 7: Market Segmentation, Targeting, and Positioning

advertisement