The Positioning of Educational Research

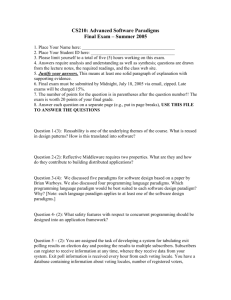

advertisement