Model Languages_ by sunandshadow.

advertisement

To Create a Language

by Mare Kuntz

Every one of us is, of necessity, a student of language. Some people find

language such an intriguing toy that they want to build a language of their own. People

have various motivations for taking on this massive task: some want a secret code to

compose their personal writings in; some want their fictional characters to have a

fictional language to speak in; some dream of creating a lingua franca for the world to

adopt; some want to eliminate the annoying vagaries and irregularities of naturally

evolved languages; and some want to create a language in such a way that the concepts

built into it will reflect or affect the philosophy of its speakers. (Henning, “How-To

Newsletter part 1: An Introduction to the Hobby of Model Languages”, p. 1) Whatever

your motivations, this set of instructions can help you out.

The first thing to do is chose what type of language you want to make. Circle

your choices as you go along. Creating a language involves making lots and lots of

decisions, and if you don’t document these as you go along, you’re going to forget them.

I recommend keeping all the paperwork for your language in a 3-ring binder.

Naturalistic or Loglan?

A naturalistic language is naturalistic in that it has irregularities. English, for

example, has irregularly conjugated verbs (sing), irregularly pluralized nouns

(mouse), etc. Other languages have irregular gender assignments, noun

declensions, etc.

A loglan, or logical language, is perfectly regular.

Which is better? Well, would you rather your language was realistic and quirky,

or neat, tidy, and easy to remember?

A Priori or A Posteriori Lexicon? A Priori or A Posteriori Grammar?

A lexicon is the group of root words on which the vocabulary of your language is

based. The grammar is the pattern by which these root words are modified with

affixes, case endings, and tense endings, then arranged into the proper word order.

A posteriori (from after) means the language is based on one or more existing

languages. For example, the futuristic slang in Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork

Orange is based on English and Russian.

A priori (from before) means the language is completely made up. Of course, it’s

impossible to completely make up a grammatical system; the general guidelines

for what grammatical forms are possible are hardwired in every human brain.

However, you can mix-and-match grammatical elements from different languages

to get something sufficiently original to be termed a priori.

What should you choose? If you want your language to be something humans

might speak in the near future, choose an a posteriori lexicon. If you want your

language to be something that has nothing to do with present-day Earth, choose an

a priori lexicon. If you don’t find grammar interesting, or if you intend to use

your language simply as a means for encoding your writing, make your grammar

be a posteriori and just use the grammar of your native language. If you think

grammar is fun to play with, choose a priori and have fun making it up. (There

are guidelines for this below.)

Complete Language or Model Language?

A complete language is one that has more than 100,000 words of vocabulary

(English has 250,000) and a complete grammatical system, such that all the

communication that normally goes on in a society could be accomplished through

use of this language. As you may guess, making a complete language is a LOT of

work.

A model language is one in which you only work out the details necessary for

whatever you intend to write in the language.

Pick whichever suits your purposes.

Okay, now you know what you want to make. How do you make it?

The following steps are necessary to the creation of an “A Priori, Complete”

language:

(other types can skip some steps)

Choose the phonology

Choose/Design an alphabet, syllabary, ideogramy or pictogramy

Choose the syllable structure

Choose the type of accent, and assimilation rules

Create the lexicon

Create the grammar

Translate the desired text (Rosenfelder, p. 1)

Phonology:

Unless you want to create a sign or other non-verbal language, you need to have

some sounds with which your language can be spoken. The phonology of your language

is the set of sounds used to communicate your language. If you are using an a posteriori

lexicon, simply use that language’s phonology. You may want to represent spelling or

pronunciation as having drifted from their present day forms; how to do this is explained

in the section on Change Over Time.

If you are creating an a priori lexicon you need to design a phonology. In

designing the phonology of your artificial language you have several choices:

Choose phonemes that you are most familiar with.

Choose phonemes that appeal to you aesthetically.

Choose phonemes to maximize your phonemic inventory. (This requires a chart

and pronunciation tape or CD of the international phonetic alphabet. The tape/CD

is available at: http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/wells/cassette.htm .)

Choose phonemes that most people in the world already know or can learn to

pronounce easily.

Choose phonemes based on morphological, syntactic, semantic or other

requirements. (This is if you want to get complicated and have 2 or 3 versions of

some phoneme type because the language’s philosophy calls for this type of

symmetry, or have the number of phonemes of each type fit some kind of

numerology system.)

Choose sounds that humans can make but don’t usually use linguistically:

whistles, clicks (some languages do use these), kiss-noises, purrs, etc.

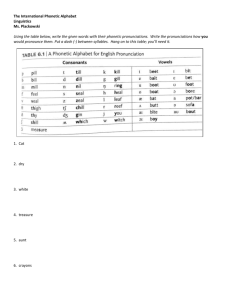

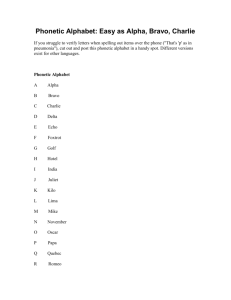

What kinds of sounds are there to choose from? And how do you write them down? The

phonetic alphabet!

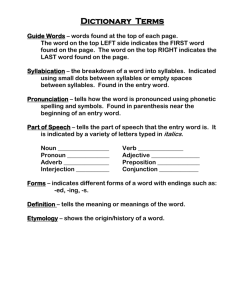

Pronunciation Key:

p pill

t

till

k kill

i

beet

I bit

b bill

d

dill

g gill

e bait

bet

m mill

n

nil

ring

u boot

U foot

f

s

sill

h hill

o boat

bore

v veal

z

zeal

l

bat

θ

chill

r reef

^

ð thy

j

j

aj bite

ʍ which

j boy

w bout

fill

thigh

shill

Jill

leaf

you

w witch

butt

a bought

sofa

azure

The symbols not included in this key don’t exist in English. To hear examples of them

you will need to get the tape or CD from the IPA or hear them from someone who speaks

a foreign language that has that sound.

(This chart of the International Phonetic Alphabet may be freely copied on

condition that acknowledgement is made to the International Phonetic Association.)

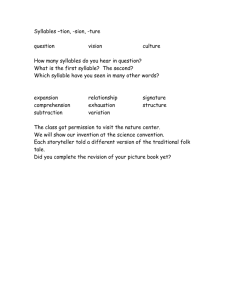

Syllable Structure:

(skip if using an a posteriori lexicon)

Now that you have your phonemes, you need to build syllables out of them. The

syllable structure of every language on Earth is included in the formula: {C}V{V}{C}

where {} indicates zero or more of the enclosed item, C indicates a consonant, and V

indicates a vowel or semivowel. Keep in mind that by vowel or consonant we mean one

sound, not one letter – “th” for example only counts as one consonant. All existing

languages limit this structure in some way to prevent very-hard-to-pronounce syllables.

The maximum syllable allowable in any language would be CCCVVCCC (e.g. sprites).

Accent:

(skip if using an a posteriori grammar)

When you speak you emphasize some syllables and de-emphasize others; this is

an accent pattern. All human languages have some type of accent pattern because this

helps hearers perceive words accurately. There are two types of accent that I know of:

stress and tonal.

English and Latin have stress accents. In English this means that unstressed

vowels are all pronounced []. In Latin this meant that []s tended to become

other vowels. In Latin simple rules determined which syllables were accented; in

Eenglish the accent(s) are random and must be memorized for each word.

Japanese, Greek, and Mandarin have tonal accents. The number and type of tones

differs, but basically syllables are accented by being spoken with a higher or

lower pitch. There is no vowel assimilation in tonally accented languages.

Assimilation:

(skip if using an a posteriori lexicon)

Frankly, assimilation is one of the most irritating, messy aspects of language.

Assimilation can occur whenever two syllables are combined into a word. For example,

let’s take the prefix ‘in’, meaning ‘not’. Theoretically this prefix is just stuck on the front

of a word, as with ‘intolerable’. But if the word begins with certain sounds, the last

consonant changes so that the two are easier to say together: ‘impossible’, ‘irresponsible’,

‘illegitimate’. Assimilation can also happen the other way around, with the first sound of

the root word changing to agree with the last sound of the prefix. Assimilation happens

only with consonants, and can be predicted mostly by knowing whether the consonants

are voiced or unvoiced. For example, the voiced [b], [d], and [g] regularly change to or

from the voiceless [p], [t], and [k], respectively. You will need to take all of this into

account when choosing syllables to use as affixes and when creating two-syllable

compounds in your language.

Assimilation also occasionally occurs between words: for example the choice of

the article ‘a’ or ‘an’ before a noun. However, this is rare enough that it would be safe to

ignore in your language creation.

Alphabet/Syllabary/Ideogramy/Pictogramy:

English uses an alphabet – a system in which one letter represents one sound. At

least theoretically one letter represents one sound – English has problems with this

because we use a Roman alphabet which doesn’t distinguish between long and short

vowels and has no symbols for the two types of ‘th’ sounds. The phonetic alphabet, as

described above, was invented so that linguists could indicate each sound in every with

one symbol.

If you want, you can just write your language in the phonetic alphabet. If you

want to, however, you can create an alphabet, Syllabary, Ideogramy, or Pictogramy with

which to write your language.

Creating an alphabet is simple – write down the phonetic symbols for all of the

phonemes your language will use, then make up a symbol for each one.

Remember, simple is better – no English letters of the alphabet take more than 4

strokes to write (E) and most take less than that. People are lazy, efficiency is

good, and you’ll have less fun playing with your language if you keep getting a

hand cramp from writing the letters. Do you want a print alphabet, a cursive

alphabet, a brush-painted alphabet, or a stylus-made alphabet? For a print

alphabet make each letter out of straight lines. For a cursive alphabet make each

letter start with a tail at a standard point around the letter area. (The standard

point depends on whether your language is written left-to-right, up-to-down, or

whatever.) Now draw the letter without letting your pen tip leave the paper, and

end with a tail that goes to the standard point where the next letter will begin.

(I intend an illustration for this)

For a brush-painted or stylus-made alphabet, keep in mind that the lines will vary

in thickness and what the tips of the lines look like depending on how the brush or

stylus is shaped.

A syllabary is a system in which a letter or other written symbol represents not

one phoneme but a whole syllable. These are best for languages that only allow

simple syllables or have only a few phonemes – if we created one for English it

would have to have something like 8,000,000,000 symbols. The calculation used

here is [(21 consonants * 20 consonants * 19 consonants)2 * [(12 vowels * 11

vowels) + 12 vowels] – illegal consonant combinations. Modified syllabaries are

more efficient: for example, you could have one symbol for each possible

consonant cluster and one letter for each vowel. To write English in such a

system would require something less than 7,990 symbols. Mandarin, which

allows fewer phonemes and syllables, can be written with only 3,000 such

symbols.

An ideogramy is a set of abstract pictures that represent sounds, syllables, or

whole words, e.g. Cuneiform, Mandarin.

A pictogramy is a set of more-or-less meaningful pictures that represent sounds,

syllables, or whole words, e.g. Egyptian. Another example is Linear B:

(I need to re-draw this so I’m not violating copyrights, but I ran out of time.)

Lexicon:

Words are created in several distinct ways:

Arbitrary Coinage

“hobbit”, “Jabberwocky”

This is the simplest way of creating a word, and the one you will be using most if

you are creating an a priori lexicon. Simply take the phonemes you have chosen,

use them to generate syllables that are legal to the syllable pattern you have

chosen, and then assign a meaning to each resultant syllable. A shareware

program is available from www.langmaker.com to generate acceptable syllables

and track the pieces of lexicon the linguistic craftsperson creates. This program

also comes with a file of dictionary entries of 3,000 core terms to help you create

your lexicon.

Onomatapoeia

“coo”, “chirp”

In assigning meaning to your syllables, let onomatopoeia be you guide when

possible. This is a principle of naming things according to the sounds associated

with them. Terms having to do with water might have ‘sh’s in them, a cat might

be called a ‘raow’, etc.

Affixes

“inside”, “absof-inglutely”, “sillyness”

An affix is literally “something stuck onto” a root word. There are four possible

types of affixes: prefixes, which occur at the beginning of a word, infixes, which

occur at the end of a word, suffixes, which occur at the end of a word, and

circumfixes, which occur in two pieces bracketing a word. I’m sure you know

many examples of prefixes and suffixes. Infixes, while common in many

languages, only appear in English with swear-words, as in the example. English

has no circumfixes, but if we did, it would look something like *nesweetss for

sweetness. Languages which use a lot of affixes are called agglutinating

languages. The created language Klingon, for example, can have as many as nine

suffixes stacked at the end of a word. It is possible to create a language that has

no affixes, or uses particles, like Mandarin. (Particles are separate words that

have the meaning of affixes.) Prepositions are good things to make affixes; a

complete list of the prepositions occurring in English is included in an appendix at

the end of this text.

Prepared Phrases

“punctuated equilibrium”

This is where several words have been overloaded (made more specific and

complex, or more sweeping and general) with a new meaning when they appear in

a specific combination. For example, in Nancy Kress’ Brainrose the phrase

“purple martins flying”, while meaningless in reality, is given all sorts of

catastrophic overtones by the characters in the book. The phrase ‘punctuated

equilibrium’ literary means a balance which is periodically disturbed, but the

phrase has a much more complicated meaning in terms of evolutionary theory.

“feminazis”

Combination/Portmanteau/Blend

Very standard way to make all sorts of new words. Just stick two root words

together, joining them with a vowel if necessary.

Part of Speech Migration

“to eyeball something”

This is done in English every day. Making your language do this consistently can

say interesting things about how your culture looks at the world.

Namesakes/Eponymity

“Halley’s Comet”, “Linux”

Nothing spells narcissism like naming something after oneself.

Abbreviation

“fax” from “facsimilie”

Usually only useful when writing about the future of a real culture. These can be

used as futuristic street slang or technical jargon, less often as a political term

Metaphor/Metonymy Synecdoche

“crown” stands for “king”

All languages do this. Basically a root ends up being used in not-quite correct

ways because it was once used metaphorically, and this metaphor became

permanent.

Grammar:

(skip if using an a posteriori grammar)

Now you need some grammar. I can’t teach you everything about grammar in

this text – it would take a whole book to do so. You absolutely need to know what the 8

parts of speech are and how they are used: noun, verb, adjective, adverb, conjunction,

article, interjection, preposition. You absolutely need to know the ways in which a

verb/noun can be conjugated/declined/inflected: person, number, gender, case, tense,

voice, mood. You absolutely need to know how to cut sentences into clauses, and how

word order can contain meaning or not, depending on how a language uses it.

If you don’t know that stuff you have 2 choices: use English grammar or go read a

book. Here are some useful books and two somewhat useful webpages:

Fromkin, Victoria, and Robert Rodman An Introduction to Language

Comrie, Bernard The World's Major Languages

Lyovin, Anatole An Introduction to the Languages of the World

Chomsky, Noam Transformational Generative Grammar

Rosenfelder, Mark “The Language Construction Kit.”

http://www.zompist.com/kit.html

Henning, Jeffrey “Invent Your Own Language.” http://www.langmaker.com/

While reading, you can record your impressions with this checklist:

How are nouns formed, what properties about them need to be indicated, and how

will these properties be indicated?

Gender:

Number:

Case:

Declensions by thematic vowel or otherwise:

Affixing:

Do you want any inflectives? (An inflective is an affix that has syntactic

rather than lexical meaning – for example ‘Jane’s’, ‘I call/ he calls’.)

Does your language use articles?

Pronouns?

How are verbs formed, what properties about them need to be indicated, and how

will these properties be indicated?

Do verbs and nouns have separate, unified, or regularly related roots?

Gender:

Person:

Number:

Tense:

Voice:

Mood:

Adjectives:

Adverbs:

Conjunctions:

Prepositions:

Word order:

If you’re creating a naturalistic language you also need to decide what’s going to be

an exception to the rules, and how this is going to be an exception:

Miscellaneous:

Handy List of All English Prepositions By Meaning

Toward

Away from

Through

Around

Before, in front of, prior to, previous

After, behind, past

At, around, about

Near

Far

Along

Across

Aslant

Astride, astraddle, athwart, aboard

Beside, along side

Afoul of, tangled with

Up

Down

North

South

Over, above

Under, below

On

Off of

In, into

Out of, from, forth

Opposite, facing

Where, there, when, then

Between

Among, amid, amidst

Meanwhile, while, during

As long as, for a duration

Yet, already

Starting at, from

Ending at, to

Until

Since

Throughout

Together

Apart

For the purpose of benefiting (I did it for Sam.)

Transfer of posession, for, to

About, with regard to, concerning, over, considering, re, apropos of

Regardless, irrespective

According to

For, pro

Against, anti

Except, other than, aside from

In the role of, with the authority of, as

In the manner or style of, as, like, ala

On the other hand, however

At a rate of, apiece, per

Because of, by

If

Also, besides, in addition to, together with, over and above

Agency, by (It was done by Sam.)

In preference to, rather than

This is more or less X than that

Similar to, like

Different from, unlike

Possessing, with, having

Not posessing, without, sans, sine

Made of

Because of, owing to, due to, caused by, resulting from

In as much as it is, qua

Instead of, replacing

By means of, via, with

If then

Within X range of Y, Y give or take X

Handy list of Conjunctions

And, not only but also

And not

But, But not, yet, and yet, but still, whereas

Or, either or

Or but not both

So that, so then, therefore

Neither nor