Economic History and Business History: Mutual Contributions and

advertisement

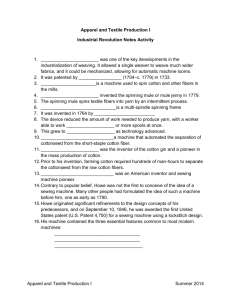

Economic History and Business History: Mutual Contributions and Future Prospects By Steven Toms (University of York) and John Wilson (University of Liverpool) Correspondence: J.S. Toms Professor of Accounting and Finance and Head of School The York Management School Freboys Lane University of York, Heslington, York, YO10 5GD, UK Tel: (44) 1904-325019 Fax: (44) 1904-434163 Email: steve.toms@york.ac.uk http://www.york.ac.uk/management/staff/StaffProfiles/SToms.htm 0 Abstract In the very first edition of Business History T.S Ashton described economic history as 'the parent study', arguing that business history's principal role was to highlight micro-economic perspectives. Much has happened in the intervening 52 years to undermine this view. Indeed, business history would now claim to be a discipline in its own right, with flourishing academic journals, several textbooks, and a plethora of literature of both a generalist and case-study form. At the same time, it is vital not to overlook the enormous complementarities that link economic and business history, specifically for example in terms of better understanding such concepts as entrepreneurship, industrial structure, industrial relations, the impact of government policies, and the roles played by financial institutions in a modern economy. Business historians now think as much about the economic, social, political and cultural environments in which business operates as they do about business operations in their micro-economic context. Meanwhile economics and social science theory more generally has evolved new conceptual frameworks and methodological tools that allow the development of new perspectives in business and economic history. One might therefore argue that the two disciplines are now bound together much more extensively than they would appear to have been in the 1950s. This paper therefore argues that too much divergence between economic history and business history is both undesirable and unnecessary. Such an outcome might arise for example if business history were to become too strongly subsumed within the business school research agenda, embracing sociological and cultural methodologies to the exclusion of a productive relationship with economics. A further risk would be that micro-economic theory that has become useful for firm level analysis in fields such as corporate strategy is also lost to the history agenda. At its embryonic stage business history complemented economic history as a tool of further analysing the residuals in total factor productivity models. Today it offers more than that, including dynamic theories of resource creation, sustained competitive advantage and corporate control. Economic history meanwhile provides suitable methodologies for business historians to model the performance of entrepreneurs or the consequence of managerial decisions. To exemplify the advantages of these overlapping approaches, the paper revisits a key theme in the economic history literature from a business history perspective: the loss of British competitiveness at the corporate level and consequent economic decline from the middle of the nineteenth century onwards, referred to in shorthand as the entrepreneurial failure hypothesis. An archetypal case study, Lancashire cotton textiles, is used for the purposes of reviewing this hypothesis. It is appropriate to do this, not least because business and economic historians have neglected what had been a productive research programme two decades ago. Most of the residual work has been done by economic historians, without reference to business history approaches, leaving an important gap for business historians to fill in a way which is helpful to the economic history agenda. The paper begins by tracing the origins of business history as a branch of economic history reviewing recent developments in business history as it has developed into a discipline in its own right. It then examines aspects of management theory that have inputted into this process, differentiating between those that are helpful to achieving a coherent programme of economic/business 1 history research and those that are inimical. The former include the resource based view of the firm, and the related notion of dynamic capabilities, which when linked to processes of governance and corporate accountability, offer the potential to link economic theory and economic history with business history by providing a micro theory of the operation of the firm. The paper then updates the entrepreneurial failure literature in economic and business history and reexamines the evidence on Lancashire cotton case study using this integrating theoretical framework. In doing so it shows that there is much to be gaining from potential complementarities in a future economic and business history research programme addressing this, and wider debates. In outlining these potential complementarities for future research the paper will also set out an agenda for how economic and business history can work together in providing better insights into the operation of economic forces. 2 Introduction The paper begins by tracing the origins of business history as a branch of economic history reviewing recent developments in business history as it has developed into a discipline in its own right. It then examines theories that have developed since these original issues were investigated. The resource based view of the firm, and the related dynamic capabilities literature in particular, offer the potential to link economic theory and economic history with business history by providing a micro theory of the operation of the firm. In this perspective competitive advantage is explained as a consequence of unique resource endowments and imperfections in factor markets. It is concern with such imperfections in specific historical contexts that drove the original research programme of economic historians to investigate the firm-level causes of declining British competitiveness. The paper then updates the entrepreneurial failure literature in economic and business history and re-examines the evidence on Lancashire cotton case study using this integrating theoretical framework. In doing so it shows complementarities in that a there future is much economic to and be gaining business from potential history research programme addressing this, and wider debates. Business history: origins and recent developments Business History was originally regarded as a branch of economic history in the USA and in Britain.1 It emerged in Britain emerged in the 1950s following the publication of a series of influential company histories and the establishment of Barry Supple, ‘Introduction: approaches to Business History, in Supple, B. (ed.) Essays in British Business History, Clarendon: Oxford, 1977, pp.1-8. 1 3 the journal Business History in 1958 at the University of Liverpool. The most influential of these early company histories was Charles Wilson’s History of Unilever, the first volume of which was published in 1954. Other examples included Coleman’s work on Courtaulds and artificial fibres, Alford on Wills and the tobacco industry, Barker on Pilkington’s and glass manufacture.2 These early studies were conducted by primarily by economic historians interested in the role of leading firms in the development of the wider industry, and therefore went beyond mere corporate histories. Although some work focused on the successful industries of the industrial revolution and the role of the key entrepreneurs, in the 1970s scholarly debate in British business history became increasingly focused on economic decline. For economic historians, the loss of British competitive advantage after 1870 could at least in part be explained by entrepreneurial failure, prompting further business history research into individual industry and corporate cases. The Lancashire cotton textile industry, which had been the leading take-off sector in the industrial revolution, but which was slow to invest in subsequent technical developments, became an important focus on of debate on this subject. Mass and Lazonick for example argued that cotton textile entrepreneurs in Britain failed to develop larger integrated plants on the American model; a conclusion similar to Chandler’s synthesis of a number of comparative case studies.3 John Wilson, and Steven Toms, J.S ‘Fifty years of Business History’, Business History, 2008, Vol.50 (2), pp.125-26. Leslie Hannah, ‘New Issues in British Business History’, Business History Review, summer 1983, Vol.57(2), pp.165-174. 2 William Mass, & William Lazonick, `The British Cotton Industry and International Competitive Advantage: the state of the debates,' Business History, XXXII (4), (1990) pp. 9-65. Chandler, A., Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism, Cambridge Mass.: Belknap Press (1990). 3 4 British business history began to widen its scope in the 1980s, reflecting increasing involvement in the discipline by Business and Management School academics.4 Areas of investigation have included management strategy themes such as networks, family capitalism, corporate governance, human resource management, marketing and brands, and multi-national organisations. Employing these new themes has allowed business historians to challenge and adapt the earlier conclusions of Chandler and others about the performance of the British economy.5 A framework for economic and business history Divergence between the disciplines of economic and business history might arise where business historians are merely atheoretical,6 explicitly reject the use of economic methodologies or simply ignore them, preferring instead to investigate the evolution of managerial culture.7 For example Rowlinson and Procter suggest that reliance on economic theory, professed objectivity, and complacency towards post-modernism, act as barriers to the development of business history as a theoretically informed of discipline that can relate to the agenda of Matthias Kipping and Behlul Usdiken, ‘Business history and Management Studies’, in Geoffrey Jones and Jonathan Zeitlin (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Business History, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp.96-119. 4 Steven Toms, and John F Wilson, ‘Scale, Scope and Accountability: Towards a New Paradigm of British Business History.’ Business History (2003), 45(4): 1-23. 5 6 Leslie Hannah, 'Entrepreneurs and the social sciences'. Economica (1984) 51: 219-234. For an overview of the issues see Michael Rowlinson, Stephen Procter ‘Organizational Culture and Business History’, Organization Studies, (1999), 20(3), pp.369-96. For a discussion of the symbiosis between business history and sociology, see Oliver Westall 'British business history and the culture of business' in A. Godley and O.M. Westall (eds.) Business history and business culture. (1996) Manchester: Manchester University Press. 21-47. 7 5 organization studies.8 However desirable such an outcome might be for organization studies, the gains for business history are less obvious. Indeed the call for such an alliance reflects divisions with the discipline of management studies. Organization studies, as understood by Rowlinson and Procter, represents only one branch of organisation theory, which has carried on almost unnoticed by the US mainstream literature, and remains underpinned by organisational economics. In turn, this is only one branch of a management literature which also includes strategy and governance. The latter approaches rely on various forms of applied economics, such as the evolutionary and new institutional approaches.9 It is in these economics-based elements of management studies that the greatest potential lies for the development of a theoretically consistent approach to economic and business history. There are potential benefits for management studies as well, although these branches typically do not engage in historical analysis.10 From the point of view of economic history, these approaches offer some distinct advantages. For example, the resource based view has attracted significant attention in the strategic management field.11 Business history has begun to use strategic management models that are rooted in applied economics 8 Rowlinson and Procter ‘Organizational Culture and Business History’, p.370. For an overview of developments in these branches of management studies see Kipping and Usdiken, ‘Business history and Management Studies’. 9 An obvious example is Teece’s influential dynamic capabilities approach, which is time dependent but has not embraced longer run historical analysis. Teece, D., Pisano, G. and Sheun, A. ‘Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management’, Strategic Management Journal, (1997)Vol.18, pp.509-33. 10 For a recent review of the former, see Acedo,F.J., Barroso, C., and Galan, J.M (2006), “The resource-based theory: Dissemination and main trends”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol.27, No.7, pp.621-636. 11 6 in a framework that goes beyond Chandler, integrating the resource based view of the firm and resource dependency perspectives.12 Some conclusions about the determinants of corporate behaviour in the UK and the US have already been drawn.13 However, the economic history literature has made little use of the RBV approach to date although there are some recent exceptions.14 There have also been limited examples of integration of corporate governance and in a transaction cost framework.15 A number of useful research questions can be addressed, using the resource based view of the firm and resource dependency perspectives, for example: 1. What are the unique difficult to replicate resources possessed by individual firms that enable them to earn long run abnormal profits? 2. How can such profits be distinguished from monopoly rents? 3. How are unique non-replicable resources valued in relation to the abnormal profit streams generated by their employment?16 For example Toms and Wilson, ‘Scale, Scope and Accountability: Towards a New Paradigm of British Business History’ 12 Toms and Wilson, ‘Scale, Scope and Accountability: Towards a New Paradigm of British Business History’, for example in the UK and US case, there are specific pathdependent institutional differences in the market for corporate control with consequences for firm structure and behaviour, S. Toms and M. Wright (2005), ‘Corporate Governance, Strategy and Refocusing: US and British Comparatives, 1950-2000', Business History, Vol.47(2); pp.267-295. 13 Carol M. Connell ‘Firm And Government As Actors In Penrose's Process Theory Of International Growth: Implications For The Resource-Based View And Ownership– Location– Internationalisation Paradigm Australian Economic History Review, (2008) Volume 48, Issue 2, pages 170–194. Paul L. Robertson, Gianmario Verona PostChandlerian Firms: Technological Change And Firm Boundaries, Australian Economic History Review, Volume 46, Issue 1, pages 70–94, March 2006. 14 Francesca Carnevali, ‘Crooks, thieves, and receivers’: transaction costs in nineteenthcentury industrial Birmingham Economic History Review, 2004, Vol 57, 3, pp. 533–550. 15 The question returns us to an unresolved debate in economic theory. Cohen, A.J. and Harcourt G.C. (2003), ‘Whatever happened to the Cambridge capital theory controversies’? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17, 199-214. 16 7 4. Once earned, how are abnormal profits distributed, accumulated and reinvested in the firm/industry/economy? When considering debates that are important in both the economic and business history literatures, for example the proposition that major firms have difficulties over a long period in sustaining their initial endowment of resources and capabilities.17 A potentially useful application of this is to revisit the hypothesis of entrepreneurial failure in late Victorian Britain. It is difficult to see how the question of entrepreneurial failure can be resolved without considering at least these questions separately, as well as assessing their collective impact. Failing entrepreneurs need to be shown not to be investing in non-replicable resources, suffering lower profits as a result and failing to invest/reinvest resources in their firms. Considering these aspects and their holistically relationship gets us closer to a theory of the firm that is best tested empirically by a combination of econometric and archival methods. Combined research methodologies also have the advantage of synergistic addition to the weight of evidence brought forward to examine any given hypothesis. The entrepreneurial failure debate The failure of the late Victorian entrepreneur has been justified by evidence of falling productivity growth rates for the British economy relative to overseas competition.18 An alleged reason for loss of competitive advantage was the L. Hannah, ‘Marshall’s “Trees” and the Global “Forest”: Were “Giant Redwoods” Different?’ IN N. Lamoreaux, D. Raff and P. Temin (eds) Learning by Doing in Markets, Firms and Countries, Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1999). 17 18 Phelps Brown and Handfield- Jones, `The climacteric of the 1890s', pp. 266-307, identified general economic failure based on a review of output per operative data for selected key industries. Coppock, `The Climacteric of the 1890s: a critical note' argued the 8 technological conservatism of British entrepreneurs and an associated hypothesis about the rationality of the choices made.19 There have also been sociological arguments about their preference for wealth consumption over productive reinvestment20 and in the case of the cotton industry in particular, problems caused by excessive vertical specialisation. At its conclusion in the early 1990s, the debate had polarised between those who believed that Lancashire entrepreneurs made rational choices and those who believed that optimisation within normal constraints was an insufficient test of entrepreneurial ability, and that entrepreneurs should have overcome constraints that otherwise prevented the restructuring of the industry.21 Since the 1980s the debate on entrepreneurial failure has subsided to some extent, but more importantly has developed along separate lines in the business and economic history literatures. In economic history claims of entrepreneurial failure have become more muted or nuanced and less well supported by quantitative evidence.22 For example, using a Total Factor slowdown was attributable to cotton, and dated from the 1860s, pp. 1-31. Floud, and McCloskey, The economic history of Britain since 1700, noted a period of stability in productivity 1873-1890 with a decline from then on. In contrast, other estimates suggest any retardation prior to 1899 was explicable solely by the agricultural and mining sectors, Matthews, Feinstein, and Odling-Smee, British economic growth, 1856-1973, p.606. Aldcroft, `The entrepreneur and the British economy' pp. 113-34; Landes, The unbound Prometheus; McCloskey and Sandberg, `From damnation to redemption' pp. 89-108; Sandberg, Lancashire in decline. 19 Aldcroft, `The entrepreneur and the British economy' pp. 113-34; Wiener, English culture; these views have been criticised in Rubinstein, Capitalism, culture and decline. 20 For the main interpretations; Sandberg, Lancashire in decline; Lazonick, `Competition, specialization and industrial decline', pp. 31-8; Lazonick, `Factor costs', pp. 89-109; Lazonick, `Industrial organization and technical change' pp. 195-236; Saxonhouse and Wright, `Stubborn mules and vertical integration', pp. 87-94, Mass and Lazonick, `The British cotton industry', pp 9-65. 21 Crafts, (2004) Long-Run Growth. In: Floud R. and Johnson P. (Eds.), The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain, vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 124. 22 9 Productivity analysis, Crafts et al attribute declining productivity to managerial failure, for example in flawed investment decisions, but also regulatory failure.23 Business historians have examined the entrepreneurial failure debate using industry and firm level case studies.24 Scott, in a case study of the coal industry, argues that the diffusion of high throughput technology, hitherto used a measure of entrepreneurial performance, was limited by technological path dependencies and fragmentation of property rights. Fleming McKinstry and Wallace analyse the case of North British Locomotives showing that entrepreneurs in general made rational decisions, and were able to some constraints such as access to financial resources, but could not overcome others such as government policy driven shifts in the demand function. 25 Arnold and McCartney compare national and corporate level accounting data in the period 1855-1914 and conclude that poor entrepreneurial performance does not correspond to poor financial performance, suggesting that economic decline might be better explained by the events of the First World War and their aftermath.26 Taken together, these studies suggest the beginnings at least of alternative hypotheses to explain the decline of the British economy, based on path dependency, financial constraints and dislocation of world markets following the First World War. Nicholas F.R. Crafts, Terence C. Mills & Abay Mulatu ‘Total Factor Productivity Growth On Britain’s Railways, 1852-1912: A Reappraisal Of The Evidence’, Explorations in Economic History, 23 Peter Scott, Path Dependence, Fragmented Property Rights and the Slow Diffusion of High Throughput Technologies in Inter-war British Coal Mining, Business History, Vol. 48, No. 1, 2006, 20–42 24 AIM Fleming, S. McKinstry and K. Wallace, ‘The Decline and Fall of the North British Locomotive Company, 1940–62: Technological and Financial Mismanagement or Institutional Failure?’, Business History, 2000, vol.42(4), pp.67-90. 25 Tony Arnold and Sean McCartney, ‘Can macro-economic sources be used to define UK business performance, 1855-1914?’ Business History, 2010, 52: 4, 564 — 589. 26 10 Examples from the Lancashire textile industry Rings vs mules revisited Since the early 1990s, economic historians have re-examined aspects of entrepreneurial failure in cotton textiles, with particular reference to the issue of technological choice and alleged conservatism of Lancashire entrepreneurs. In general recent evidence from the economic history literature has supported the rehabilitation of Lancashire entrepreneurs. For example, Leunig shows that in Lancashire mule spinning was more productive and entrepreneurs’ choices were therefore rational.27 Saxonhouse and Wright show that decisive improvements in preparatory technology, in particular Casablanca’s high drafting method, meant the mule lost its advantage on finer counts, but only from the 1920s onwards.28 Ciliberto has re-examined the adoption of ring spinning and automatic weaving using firm level data for the whole industry between 1884 and 1913. Industry level data shows that there was at least an association between increased adoption of ring spinning after 1902 and the establishment of the British Northrop loom company in 1904.29 These studies confirm the view that Lancashire entrepreneurs made rational decisions in terms of their choice of Timothy Leunig (2001), ‘New Answers to Old Questions: Explaining the Slow Adoption of Ring Spinning in Lancashire, 1880–1913’, The Journal of Economic History, 61, (2): 439–66. Timothy Leunig (2003), A British Industrial Success: Productivity in the Lancashire and New England Cotton-Spinning Industries a Century Ago, Economic History Review, 56, (1): 90–117. 27 Gary R. Saxonhouse and Gavin Wright, (2010) ‘National Leadership and Competing Technological Paradigms: The Globalization of Cotton Spinning, 1878–1933, Journal of Economic history, Vol 70(3), pp.535-566. 28 Federico Ciliberto, (2010) Were British Cotton Entrepreneurs Technologically Backward? Firm-Level Evidence on the Adoption of Ring-Spinning, Explorations in Economic History, Vol.47, 4, pp.487-504. 29 11 technology. They also tend to relocate the search for entrepreneurial failure in the 1920s rather than in the late Victorian era. Recent business histories have tended to confirm these conclusions. Firm specific examples of the adoption of ring spinning confirm the story of technological path dependency and superior productivity of the mule. Strong regional path dependency explained the establishment of the first ring spinning mill, New Ladyhouse Mill at Milnrow near Rochdale in 1877, and subsequent investments at the same location in the early 1880s with the establishment of Haugh and New Hey Mills.30 In this area there had been an established tradition of using throstle spinning, which like ring spinning was a continuous method, for producing coarser warp yarns.31 These experiments in ring spinning were described as a ‘leap in the dark, involving great risk’32. One reason for this was the cost structure and productivity differed considerable from mule spinning. Table 1 compares the wage cost per spindle and per hand in the new ring mills to a comparable sample of mule mills in the adjacent Oldham area, comparative percentages by cost category and spindles per hand for the Milnrow group are compared to the industry average for mule spinning. The data in table 1 provide strong evidence that labour intensity was Rochdale Local Studies Library (RLSL), New Ladyhouse Cotton Spinning Co. Ltd, Memorandum and Articles of Association; ‘Milnrow Ring Spinning Companies’, Rochdale Observer, 28 June 1890, p. 4.Few other significant ring mill constructions occurred before the early 1900s, notable exceptions being the Palm (1884), specialising in strong rope yarns, the Nile (1898) in Oldham, Burns Ring Spinning Co. Ltd at Heywood (1891) and the Era (1898) in Rochdale. For a list of newly floated mills, see Jones, thesis, pp. 221–3; for Palm Mill see the company’s advertisement in the annual editions of J. Worrall, The Cotton Spinners and Manufacturers Directory for Lancashire (Oldham); for Era Mill see Era Ring Mill Company Ltd, History of the Era Ring Mill (Rochdale, undated), p. 1. Rochdale Observer, 4 January 1890. I am grateful to D. A. Farnie for information on the Burns Mill. 30 Toms, Steven (1998) ‘Growth, Profits and Technological Choice: The Case of the Lancashire Cotton Textile Industry, 1880-1914’, Journal of Industrial History, 1 (1). pp. 35-55. 31 32 Rochdale Observer, 28 June 1890. 12 much higher in ring spinning. Labour intensity arose from the organisation of certain process, for example doffing.33 Doffing was an unskilled task, normally assigned to teams (four per machine) of young and inexperienced workers, and their employment no doubt added to the labour intensity of ring spinning. 34 Ring spinning also required more labour in roving and other preparation stages and in other after spinning processes, such winding.35 If labour cost savings did exist, they were therefore confined to the ring spinning process itself. Meanwhile, first adopters of automatic looms, for example Tootals, experienced problematic labour relations, for example the Daubhill automatic loom strike of 1906.36 They were also reliant on ring spinning specifically for weft yarn, which was in short supply. Indeed the majority of new ring spinning capacity developed in the early 1900s was for warp and specialised yarns.37 The superior profits demonstrated in Examples of these experiments were the Milnrow ring spinners and the Fielden works at nearby Todmorden. (Toms, 1996, The finance and growth of the Lancashire textile industry, 1870-1914, unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Nottingham. S. Toms (1998) `Windows of Opportunity in the Textile Industry: The Business Strategies of Lancashire Entrepreneurs 1880-1914’, Business History, Vol. 40(1); pp.1-25) Production at the throstle section of the Fielden spinning plant at Waterside was facilitated by an 'army of doffers', Todmorden Advertiser, 9 November 1889, p. 4. 33 J.Winterbottom, Cotton Spinning Calculations and Yarn costs (London, 1921), p. 261. J. Jewkes and E.M. Gray, Wages and Labour in the Lancashire Cotton Spinning Industry (Manchester, 1935), p. 129. 34 C. Kenney, Cotton Everywhere: Recollections of Northern Women Mill Workers (Bolton, 1994), pp. 130–1. The New Ladyhouse Mill had a spindles to operative ratio of 79; a ring spinning mill in France in 1882 producing 30s twist had a spindle per operative ratio of 75. F. Merrtens,‘The Hours and Cost of Labour in the Cotton Industry at Home and Abroad’, Transactions of the Manchester Statistical Society (1894), p. 160; the comparable figure for mule spinning was 205, derived from G. Wood, ‘Factory Legislation Considered with Reference to the Wages of the Operatives Protected’, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, LXV (1902), p. 316. 35 Toms `Windows of Opportunity’ Toms, ‘The finance and growth of the Lancashire textile industry’. 36 S.J. Procter and S. Toms (2000), ‘Industrial Relations and Technical Change: Profits, Wages and Costs in the Lancashire Cotton Industry, 1880-1914, Journal of Industrial History, Vol. 3(1), pp. 54-72. For examples of early experiments in ring spun weft yarn, see the case of Fielden Brothers; S. Toms (1996), ‘Integration, Innovation and the 37 13 figure 1 arose from greater efficiency in output per spindle and specialisation through market niches.38 In summary, before 1914, it is clear that ring spinning was more efficient in capital utilisation but did not enjoy a decisive advantage because of labour intensity in pre and post spinning processes and limited competitive advantage in specialised markets. As Saxonhouse and Wright and others have shown, developments in preparatory and intermediate technology were decisive in securing the final advantage for ring spinning. These improvements, such as high drafting, did not occur decisively until the 1920s, preventing the productivity gains from efficient throughput in integrated factories being realised before then.39 A survey in 1932 noted three cases of ring spinning mills replacing low draft with high draft spinning, resulting in average improvements in labour productivity of 49.3 %.40 Progress of a Pennine Cotton enterprise: Fielden Bros. of Todmorden, 1889-1914’, Textile History, Vol. 27 (1); pp.77-100. S. Toms, The finance and growth of the Lancashire textile industry, 1870-1914, unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Nottingham. In 1890, there were 400,000 ring spindles installed in the Rochdale district, producing a weekly output 17,200,000 hanks (Rochdale Observer, 4 January 1890), or the equivalent of 43 per spindle. The comparable output of a mule spindle in 1893 was 31 hanks (T. Thornley, Modern Cotton Economics, London, 1923, p. 302). With the emergence of the cotton industry, Rochdale adapted its traditional capacity in flannels and developed flannelettes, the latter being introduced in 1883. The district also specialised in supplying strong yarns, eg for tyres to the motor industry (Farnie, ‘Cotton towns’, p. 44). 38 Toms, ‘Growth, Profits and Technological Choice’, D. Higgins and S.Toms, ‘Capital Ownership, Capital Structure and Capital Markets: Financial Constraints and the Decline of the Lancashire Cotton Textile Industry 1880-1965’, Journal of Industrial History, 2001, 4 (1). pp. 48-64. S. Toms and M. Beck (2007), The Limitations of Economic Counter-Factuals: The Case of the Lancashire Textile Industry, Management and Organizational History, 2(4), pp.315-330. H. Catling, The Spinning Mule, Newton Abbot: David and Charles (1970), p.189; Noguera, S. Theory and practice of high drafting, privately published (1936). pp.20-3, L Tippett, A Portrait of the Lancashire Cotton Industry, Oxford, Oxford Un iversity Press (1969). 39 Board of Trade, An Industrial Survey of the Lancashire Area (Excluding Merseyside), London, H.M.S.O. (1932), p. 135. 40 14 This evidence from firm level business histories confirms the much of the recent research in economic history in two important respects. First, entrepreneurs appear to have been rational in their choice of technology before 1914, and second, and related, if entrepreneurial failure in this respect did occur it was after 1918, not in the late Victorian period. However, business history research offers a further twist to the tale. Although the evidence reviewed above overwhelmingly suggests that mule spinning remained the more productive technology in Lancashire before 1914, firm level evidence on financial performance shows that ring spinning offered the prospect of superior returns.41 Figure 1 summarises the differential performance of the early ring spinning companies in Lancashire compared to a similar group of mule spinners. Tracking the difference between the returns on capital for the two groups, on profit to ring spinning was greater in almost any given year and averaged around 5% higher than mule spinning. In the context of the pre-1914 entrepreneurial failure debate, these differentials beg a hitherto unresolved question: why did entrepreneurs not follow the profit signals of the market and shift investment into ring spinning? Is it possible that their response to technical decisions was rational but that they irrationally missed a profit making opportunity that would have also placed the longer run future of the industry on a firmer footing? There are a number of possible explanations. One is that like some economists, entrepreneurs had an instinctive distrust of accounting information. However, there is considerable evidence that accounting information was robust and widely and accurately interpreted by investors and cotton operatives. 41 S. Toms (1998), `Windows of Opportunity’. 15 Moreover, similar differentials existed in terms of stock market returns.42 Superior profitability nonetheless appears paradoxical in the light of evidence about the inferior productivity of ring spinning. A possible reason, as suggested above, there were increasing niche markets for ring spinning in coarse and specialised warps and for wefts as the use of automatic weaving began to spread.43 In view of the poorer productivity of ring spinning, a possible explanation of its superior profitability is that shortages promoted higher prices and hence wider profit margins. The nature of entrepreneurial failure in Lancashire44 Even if these opportunities did exist, it does not explain why Lancashire entrepreneurs were less forthright in seizing them before 1914. Leunig’s view, that more expensive land in the Oldham and Manchester areas promoted the use of multi-storey mule mills, is well supported by the New Ladyhouse case and similar examples in the Rochdale area where land prices were lower, which used S. Toms (2002), `The Rise of Modern Accounting and the Fall of the Public Company: the Lancashire Cotton Mills, 1870-1914', Accounting Organizations and Society, Vol.27, No. 1/2, pp.61-84. S. Toms, (2001), 'Information Content of Earnings Announcements in an Unregulated Market: The Co-operative Cotton Mills of Lancashire, 1880-1900', Accounting and Business Research. Vol.31, No.3, pp.175-190. S. Toms (1998), ‘The Supply of and Demand for Accounting Information in an Unregulated Market: Examples from the Lancashire Cotton Mills’, Accounting Organizations and Society Vol. 23, No. 2; pp.217-238. 42 In 1890, there were 400,000 ring spindles installed in the Rochdale district, producing a weekly output 17,200,000 hanks (Rochdale Observer, 4 January 1890), or the equivalent of 43 per spindle. The comparable output of a mule spindle in 1893 was 31 hanks (T. Thornley, Modern Cotton Economics, London, 1923, p. 302). With the emergence of the cotton industry, Rochdale began to specialise in flannels and flannelettes, the latter being introduced in 1883. The district also specialised in supplying strong yarns, eg for tyres to the motor industry (Farnie, ‘Cotton towns’, p. 44). 43 The discussion in this section is substantially based on S. Toms, (2009), ‘English cotton and the loss of the world market’, in King Cotton: A Tribute To Douglas Farnie, Wilson, J., ed., pp.58-76, Lancaster, Carnegie. 44 16 single storey shed style construction.45 Ring mills built in the 1900s were also smaller, and tended not to provide access to the scale economies of mule spinning.46 The boom of 1907 was particularly noteworthy for investment in mule mill building projects of record scale.47 The crucial period was the early 1900s when investors faced a straight choice between ring and mule spinning in boom conditions. Speculative mill building in this period destroyed the profit margins of installed capacity and left the industry over-committed in subsequent slumps in demand.48 According to a contemporary estimate in 1935, there were 13.5 million surplus spindles of which 9.5 were in the American section and 4 million in the Egyptian section, representing plant utilisation of just 69%.49 As early as the 1880s the industry already contained over 40 million spindles.50 In other words all the capacity installed in the period of 1896-1914 was potentially surplus in the light of industry requirements after 1920. A crucial question, not hitherto addressed in the economic history literature is who was responsible for investment decisions and why were Leunig, ‘New Answers to Old Questions’. New Ladyhouse Mill was subsequently emulated by larger ring mills, notably Cromer (1906). Rochdale Observer, 28 June 1890, p. 4; D. A. Farnie, ‘The Cotton Towns of Greater Manchester’ in M. Williams, with D. A. Farnie, Cotton Mills in Greater Manchester, Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (1992), p. 44; Farnie, English cotton, p. 230. 45 S. Kenney, ‘Sub regional specialization in the Lancashire cotton industry, 1884–1914: A study in organizational and locational change’, Journal of Historical Geography, vol. 8 (1982), p. 59. 46 John Bunting floated the largest mill to date, the Times No. 2 in 1907 at 100,000 spindles (Oldham Chronicle, 28th December, 1907). 47 48 Jones, The Cotton Spinning Industry, p.3. Barlow, T.D. (1935), “Surplus capacity in the Lancashire Cotton Industry.” Manchester School, 6, pp.32-36: p.35; Robson, The Cotton Industry, Table 8, p.344. 49 50 Calculated from Robson, The Cotton Industry, Table 5, p.340. 17 apparent mistakes made. To some extent this gap has been filled by business historians and this section examines some of the biographical evidence. Samuel Odgen Ward personified the transitional phase of Oldham capitalism. As an Alderman and JP, he was committed to the co-operative movement that had underpinned earlier phases of development. Yet during the 1880s and 1890s he amassed directorships on the boards of several companies.51 Other examples in Oldham included Thomas Henthorn (1850-1913), Harry Dixon (1880-1947), William Hopwood (1862-1936), Ralph Morton (1875-1942), John S. Hammersley (1863-1933), and Sam Firth Mellor (1873-1938).52 Investments in the 1904-1908 boom differed from previous upswings in the cotton trade cycle. Much of the money for these new mills came from profits from existing mills, channelled via the estates of proprietors into personally administered flotations or acquisitions of other concerns.53 Groups of individually controlled mills but otherwise un-integrated businesses, became more clearly established.54 Their proprietors possessed access to financial resources based on reputation and personal contact.55 Strategy formulation became the exclusive From reports of company meetings (Oldham Standard, various issues, 1888/9), Ward served on the boards of Werneth, Coldhurst, Henshaw Street, Northmoor and Broadway Spinning Companies. Taylor, The Jubilee History pp.112 & 125. 51 Gurr, D. and Hunt, J. (1989), The Cotton Mills of Oldham, Oldham: Oldham Leisure Services, pp. 9-10. 52 Toms, S. (1994), `Financial Constraints on Economic Growth: Profits, Capital Accumulation, and the Development of the Lancashire Cotton Spinning Industry, 18851914,' Accounting Business and Financial History, Vol. 4 (3), pp. 364-383. Toms, S. (1996), `The Finance and Growth of the Lancashire Textile Industry, 1870-1914', Ph.D thesis, University of Nottingham, March. Toms ‘Windows of Opportunity’. 53 Toms S. (1998), `The Supply of and Demand for Accounting Information in an Unregulated Market: Examples from the Lancashire Cotton Mills', Accounting Organizations and Society Vol. 23, No. 2; pp.217-238. . 55 Tyson, R. E. (1962), ‘Sun Mill: A Study in Democratic Investment', Unpublished M.A. Thesis, University of Manchester, Thomas, W., The Provincial Stock Exchanges, London: Frank Cass and Co. Ltd (1973).962; Toms, ‘The Supply of’. 54 18 preserve of these individuals whilst managers became nominee officials at plant level, trusted only with routine, thereby precluding the emergence of professional managerial hierarchies.56 These changes created a highly unusual system of governance based on diversified directors and non-diversified shareholders (in the conventional model of Anglo Saxon economies it is the other way round). As a consequence capital ownership centralised and the industry increasingly fell under the control of speculative entrepreneurs.57 Overcapacity was compounded because corporate growth rates were strongest where private or family control was exercised and weakest where there was dependency on regional stock markets.58 Yet it was in stock market dominated Oldham, where there was the greatest expansion of capacity. Here there was the greatest accumulation of physical capital, but also the highest disbursement of dividends, such that the balance sheets of individual firms were only weakly capitalised. There were striking continuities between the investor groups in the Oldham section in the 1919-20 boom and the operations of similar groups, sometimes involving the same individuals, in the pre 1914 period. Promoters such as Bunting, Mellor, Hammersley and others dictated much of the recapitalisation.59 Outside investors were attracted using pre-1914 networks, so Toms, ‘Windows of Opportunity’ pp. 1-25; Toms, The Finance and Growth, pp. 217238; 56 57 58 Toms, The Finance and Growth, pp.226-31. Toms, ‘Windows of opportunity,’ p.3. For example as a result by 1919, promoter and share dealer Sam Firth Mellor was a director of 18 companies, and Bunting, of the same occupation held 14.Firth Mellor’s interests were: Argyll, Broadway; Fernhurst, Gee Cross Mill, Gorse, Greenacres, Hartford, Marland, Mars, Mersey, Monton, Moor, Orb, Peel Mills Co, Princess, Rugby, and Stockport Ring Mill. Mellor built up a substantial shareholding in many of these companies, for example, Argyll (7.55%), and Asia Mill (3.8%). See Higgins, D., Toms, S. and Filatotchev, 59 19 new calls were made on the likes of Manchester-based John Kenyon and William P. Hartley, (who had made money in preserves) to support the flotation of the Textile Spinning Company and the Asia Spinning Company. The Buntings, John and James Henry, were co-directors of Textile Mill. Just as in 1907, the investors of the 1919-20 re-capitalisation boom were local, inter-connected, had intensive knowledge of industry finance and were continuing well-established practice from before 1914. Evidence of individual activity allows the role of specific promotional groups to be assessed and their role in the downfall of the industry to be understood. The oligarchs who had brought about the demise of the democratic system in the Oldham district, now engineered the downfall of the whole industry. Econometric evidence also provides some support for this view. A statistical analysis of the accounts of a large sample of cotton companies taken from the period 1925-1931, shows that fewer recapitalised firms left the industry compared to non-recapitalised firms. However, in view of the excess capacity problem, it was imperative that some firms exited the industry. Ownership itself, in particular oligarchic control, now became an overwhelming exit barrier, preventing the reorganisation of the industry.60 They now pursued a rational strategy of forcing the managers of their firms to continue undercutting their competitors on marginal contracts, because the only alternative was to realise their investments at seriously deflated values, losing all the profits of their earlier speculations. In contrast to the arguments of Keynes, Bamberg and I. (2007), ‘Financial syndicates and the collapse of the Lancashire cotton industry, 19191931’, York Management School Working Paper. In total Bunting is known to have been involved in fourteen or so promotions. Farnie, `John Bunting', p.508. Higgins et al. ‘Financial syndicates’. Filatotchev, I. and Toms, S. (2006), ‘Financial constraints on strategic turnarounds’, Journal of Management Studies 60 20 others, indebtedness to the banks, seems a less important cause of weak selling and indeed firms with greater bank debt were more likely to leave the industry. Oligarchic companies were typically larger and enjoyed stronger market position, and as a result tended to be more successful than their competitors in terms of profitability. However, most of the profit was paid out as dividend, allowing some recovery of invested capital, but starving the industry of cash for re-equipment. The Manchester Industrial District An additional dimension of the entrepreneurial failure debate is the role of external economies of scale, and the extent that their availability underpinned Lancashire’s success and subsequent failure.61 Since Marshall, economists have regarded Lancashire as an archetypal industrial district.62 Analysing entrepreneurial failure over the longer run, it can be argued that the industrial district is a substitute for the market for corporate control (MCC). Where the latter is underdeveloped, the industrial district is more likely to be the agent of capital reallocation from one sector to another within that district. At the same time, firms can obtain competitive advantage by internalising higher cost market transactions or externalities.63 As the MCC develops this role can be increasingly undertaken by geographically remote stock market mechanisms, or internal capital markets, so that resource internalisation and transfer is facilitated first on a national, then international dimension. In this sense, internal managerial knowledge replaces external economies of scale as the driving force of S. Broadberry and A. Marrison, (2002) ‘External Economies of Scale in the Lancashire Cotton Industry, 1900-1950’, Economic History Review, LV(1), 51-77. 61 62 63 A Marshall, Principles of Economics, M Casson, (1987) The firm and the market, Blackwell. 21 competitive advantage. From the point of view of entrepreneurial failure, although history can repeat itself, it is unlikely to do so under similar conditions. To shed further light on the role of these factors, this section presents evidence from the business history literature on the Manchester industrial district. This cluster has been extensively analysed from a variety of perspectives by a variety of authorities, providing deep insights into the rich mixture of entrepreneurs that helped shape the commercial landscape.64 Of special interest, however, will be the work of Wilson and Singleton, who used a variant of the life-cycle model to evaluate various stages in the industrial district’s evolution since the mid-eighteenth century.65 Based on the work of Swann and illustrated in Figure 2,66 we identify and analyse the four main stages to this life-cycle. While it is difficult to devote much space to a full explanation of how each stage materialised, the main conclusion one can draw from Figure 2 is that there is no simple relationship between the establishment of an industrial district and long-term economic success. While firms might be capable of developing and extracting agglomeration economies in one period, this does not Amongst the most notable sources are: D.A. Farnie & T. Nakaoka (2000), ‘Region and nation’, in D.A. Farnie, T. Nakaoka, D.J. Jeremy, J.F. Wilson & T. Abe (eds.), Region and Strategy in Britain and Japan. Business in Lancashire and Kansai, 1890-1990 (Routledge, 2000); R. Lloyd-Jones & M. Lewis, Manchester and the Age of the Factory: The Business Structure of Cottonopolis in the Industrial Revolution (Croom Helm, 1988); L.S. Marshall, ‘The emergence of the first industrial city: Manchester, 1780-1850’, in C.F. Ware (ed.), The Cultural Approach to History (Oxford University Press, 1940); G. Timmins, Made in Lancashire. A History of Regional Industrialisation (Manchester University Press 1998); John K. Walton, Lancashire. A Social History, 1558-1939 (Manchester University Press, 1987); D.A. Farnie, ‘An index of commercial activity: the membership of the Manchester Royal Exchange, 1809-1948’, Business History, 21 (1979); D.A Farnie, The Manchester Ship Canal and the Rise of the Port of Manchester, 1894-1975 (Manchester University Press, 1980). 64 J.F. Wilson and J. Singleton, ‘The Manchester Industrial District, 1750-1939: Clustering, Networking and Performance’, in J.F. Wilson & A. Popp (eds), Clusters and Networks in English Industrial Districts, 1750-1970 (Ashgate, 2003). 65 G.M. Peter Swann, `Towards a model of clustering in high-technology industries’, in G.M. Peter Swann, M. Prevezer & D. Stout (eds.), The Dynamics of Industrial Clustering (Oxford University Press, 1998). 66 22 necessarily equip the region with an ability to cope with major changes. Indeed, the evolutionary process contains dangers, as well as advantages, with significant ‘agglomeration diseconomies’ arising from, for example, the failure to adapt to either exogenous pressures or the internal problems associated with what Olson describes as ‘institutional sclerosis’.67 Linked to this issue is another key dimension of Swann’s work on regional life-cycles, namely, the contention that in the ‘saturation’ stage clusters ought to diversify their industrial structure, rather than compete head-on with emerging rivals. This indicates the crucial importance of a district’s principal ‘changeagents’,68 given that they must play a major role in detecting signals and transmitting reliable information to the rest of the business community. Which groups performed this role in the Manchester industrial district? Did the identities of these groups change over time? To what extent did contemporaries respond to their messages? Space constraints prevent a comprehensive set of answers to these questions, but if we concentrate on the reasons why the Manchester industrial district was struggling to avoid the worst effects of the ‘Saturation’ stage (see Figure 2), one can contribute effectively to the broad debate about the quality of entrepreneurship. As Figure 2 briefly explains, by the early-twentieth century not only was the staple cotton textile industry struggling to compete with its principal rivals, but also other mainstays of the industrial district – heavy engineering, heavy chemicals and coal – were undergoing a period of severe rationalisation. Of course, apart from what we described earlier as the cotton entrepreneurs’ attempts to break out of the pattern of decline, considerable moves had been 67 M. Olson, The Rise and Decline of Nations (Yale University Press, 1982). This term has been borrowed from A. Pettigrew, The Awakening Giant. Continuity and Change in ICI (Blackwell, 1985). 68 23 made since the late-nineteenth century to diversify the region’s industrial base, with the emergence of electrical engineering, synthetic chemicals and automobile production. In addition, the construction of the Manchester Ship Canal (1887-94) and formation of the world’s first industrial estate at Trafford Park indicated how the local business community responded aggressively to the contemporary economic challenges. One of the most telling features of Trafford Park was the influx of American subsidiaries, one hundred of which had settled there by 1915. The most notable of these ventures were British Westinghouse (1899) and the Ford Motor Co. (1910). Although the latter was only an assembly operation, with Ford shipping all its components from Detroit, production increased to such an extent that by 1930 2,000 people worked for Ford. After some early difficulties, British Westinghouse also became a major Manchester employer, with 6,000 skilled engineers and technicians working for the firm in 1920, many of whom had passed through its highly regarded training school. In 1917, the original British Westinghouse operation had also been absorbed into the much stronger Metropolitan-Vickers Electrical Co. (hereafter, Metro-Vicks), creating one of Europe’s most progressive electrical and electronics manufacturers. By 1933, over 200 American firms had set up subsidiaries in Trafford Park, indicating how local business was provided with a shining example of the potential gains from diversifying into the new industries of the Second Industrial Revolution While during the early twentieth century both the Manchester Ship Canal and Trafford Park cushioned the district from some violent economic storms, one must still question the extent to which local entrepreneurs recognised the need for a wholesale conversion from traditional methods and activities. Faced with the dual challenges outlined earlier, of intensifying foreign competition and rapid 24 technological change, the Manchester business community should have devised radically new strategies, whether by overhauling the cotton industry’s traditional practices, or by moving into new sectors offering greater commercial opportunities. Of course, some members of the established business elite did acknowledge the need for diversification, because by 1914 some of the great cotton dynasties were diversifying their investments, especially into electric tramways and other utilities, using the services offered by the Manchester Stock Exchange. In 1901, the Prestwich family also invested £320,000 in Dick, Kerr & Co., in Preston, one of the new generation of electrical engineering enterprises.69 However, this was very much the exception rather than the rule, because at the heart of the Manchester business network cotton remained king until well after the First World War. In assessing the extent to which the North West should have responded to exogenous challenges, it is clear that while this region witnessed some impressive attempts at diversification, especially when compared with other old industrial regions (Central Scotland, South Wales, and North East England), by world standards the process was inadequate. Of course, it is always difficult comparing regions in different countries, given the stark contrasts in, for example, central government roles, the provision of capital, and entrepreneurial traditions. Nevertheless, there are serious questions to consider, especially with regard to the region’s preference for ‘sticking to the knitting’ and the failure of new industries (electrical engineering, automobiles, synthetic chemicals, light engineering and aerospace) to develop as rapidly in the North West as in other John F. Wilson, ‘A strategy of expansion and combination: Dick, Kerr & Co., 18971914’, Business History, 37 (1985), No.1. For evidence of investment strategies, see J.S. Toms, ‘Windows of opportunity in the textile industry: the business strategies of Lancashire entrepreneurs, 1880-1914’, Business History, 40 (1997), pp.1-25. 69 25 British and overseas regions. In particular, one must consider whether the Manchester business community developed dangerously sclerotic tendencies, severely inhibiting the emergence of more radical solutions to the district’s problems. Quite clearly, the Manchester business elite was slow to move beyond the familiar, treating diversification as a secondary issue to the central problem of reviving the cotton textiles industry.70 In effect, at the ‘saturation’ stage this elite was failing to perform its role as ‘change-agents’. In many ways, one might argue that this hesitancy was understandable. The regional business network’s beliefs, attitudes and routines, or ‘network software’,71 were geared towards collecting and evaluating information in specific ways that were not conducive to flexibility. Alternatively, one might state that the ‘network software’ was attuned mostly to the established industries, rather than to the wider market signals. This implies the existence of serious weaknesses in the district’s co-ordination and signalling mechanisms, making it increasingly difficult for the business community to respond effectively to the emerging challenges. For the reasons argued above, the 1919 cotton re-flotation boom represented a serious misallocation of capital, and the failure of regional stock exchanges and financial institutions as key components of the industrial district. Once investors committed to sunk investments, they became irreversible, such that outside assistance, either from direct government intervention or the assimilation of Lancashire into the national and international capital markets was the only way in which the industry could develop. In other words, the external economies of This is stressed especially in Sir Raymond Streat, Lancashire and Whitehall: The Diary of Sir Raymond Streat, 2 Vols, edited by M. Dupree (Manchester University Press, 1985). 70 71 Langlois & Robertson, Firms, Markets and Economic Change, pp.124-7. 26 scale based advantage of Lancashire firms were eliminated by sunk cost diseconomies as a result of a financial crisis. Failed attempts by government and the slow process of capital market development delayed the turnaround of the Manchester district by several decades.72 These conclusions contrast with the traditional views of J.M. Keynes, for whom the problem was the cotton industry’s lack of vision, and that its intensely individualistic leaders were ‘boneheads … who want to live the rest of their lives in peace’.73 While Keynes was both harsh and simplistic in his analysis of Lancashire’s difficulties, his views reflected a strong contemporary feeling that Lancashire entrepreneurs were struggling to come to terms with their problems in the ‘Saturation’ stage. Indeed, a ‘Renaissance’ was only to emerge sixty years later, stimulated more by a service-sector boom that drew in billions of pounds of investment. Conclusions The reinterpretation of entrepreneurial failure above is based on the analysis of the behaviour of crucial individuals. To assess them, it has examined their approach to crucial economic decisions: how do they create abnormal profits and once made, how are they distributed, accumulated and reinvested in the firm/industry/economy. In Lancashire, the answer is that large profits were available to individuals promoting mills, usually in the first few months if not years of their operation. The differentials arising from investment in ring spinning were substantial, but this proposition was ignored in the face of individual profits available on mill flotation. In such transactions, the larger the Filatotchev, I. and Toms, S. (2006), ‘Financial constraints on strategic turnarounds’, Journal of Management Studies. The final government attempt to rescue the industry was the Cotton Industry Act (1959); in the 1960s Courtaulds bought the rump of the industry and attempted to turn it round through a scale based internationalisation strategy. 72 73 Quoted in Streat, Lancashire and Whitehall, Vol. 2, p. 181. 27 mill, the greater the wealth that accrued to the promoter or promoter group. Because economies of scale were greater in mule mills, these investments prevailed, notwithstanding the apparent profitability of ring spinning. Although these investors were long run investors in the industry, they were only short run investors in any individual mill, relying on short run capital gains or dividends and recycling cash rapidly from existing to new mills during booms. Traditional mule spinning remained profitable before 1914, although not as profitable as ring spinning, but profits were rapidly wiped out in the slump after 1920 thwarting the opportunity for reinvestment, however technically or financial desirable it might have been by then.74 S. Toms (2009), ‘The English Cotton Industry and the Loss of the World Market’ in Wilson, J. (ed) King Cotton: A Tribute to Douglas Farnie, Lancaster: Carnegie, pp.58-76. S. Toms and I. Filatotchev (2006), ‘Corporate Governance and Financial Constraints on Strategic Turnarounds’, Journal of Management Studies Vol.43 (3), pp. 407-433. 74 28 29 30 Figure 2: The Life-Cycle of Manchester’s Industrial District. STAGE 1. Critical Mass 2. Take-Off 3. Peak Entry 4. Saturation THE MANCHESTER EXPERIENCE CHARACTERISTICS Clustering of expertise Up to 1780: development of linen and factors of production. and fustian production, controlled by Manchester merchants. Heavy investment in turnpike trusts and (from the 1760s) canals. Often associated with key 1780-1850: cotton spinning, and later inventions or innovations, weaving, becomes technologically which alongside the feasible, resulting in rapid clustering of expertise development of factory production. and factors of production Royal Exchange takes on role as give the district a regional co-ordinator. Mercantile significant competitive community augmented by foreign advantage merchants. Manchester Chamber of Commerce influences national trading policy debates. Multiplier effect results in complementary development of engineering, bleaching, dyeing. Further expansion of the canal network and railway transport pioneered in North West. Costs of clustering start to 1850-1920: cotton industry expands outweigh benefits, with to become major British exporter. rate of growth falling Increasing sophistication of away, innovation rare and Manchester mercantile community, competition increasing with Royal Exchange expanding and from lower-cost local stock exchange linked with producers. industrial investment. Little nd diversification into 2 Industrial Revolution industries, in spite of Trafford Park and Manchester Ship Canal. Rivals offer superior 1920-1939: (and continuing over the advantages for new firms next four decades): rapid decline of and decline sets in across cotton and heavy engineering, in the older district spite of (or because of?) the 1919 investment boom. Banks gain a stronger grip of strategy. Still very limited diversification of industrial base; no integration of older sectors. 31