“Premenstrual Mental Illness”: The Truth About Sarafem

advertisement

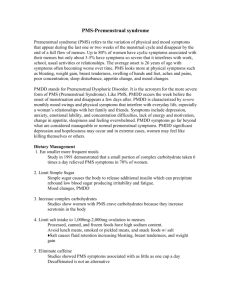

“Premenstrual Mental Illness”: The Truth About Sarafem by Paula J. Caplan, Ph.D. Published in The Network News, National Women’s Health Network, Washington, D.C.May/June, pp. 1,5,7. New television commercials and magazine advertisements tell us that women go crazy once a month: We don't just get bloated and have chocolate cravings, breast tenderness and irritability, but we become mentally ill and need to be treated with the drug Sarafem. The Internet is buzzing with messages from women insulted by ads that depict women as shrews. Neither the drugs nor the ads would exist without close interactions among the American Psychiatric Association, which creates the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), Eli Lilly and other pharmaceutical companies, the media, and women who sometimes feel physically bad and/or terribly upset – and long for respect for those feelings. Since the early 1980s, when influential DSM authors invented the alleged mental disorder now called “Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder” (PMDD), a cultural climate friendly to the view of women as emotionally out of control rapidly reified “PMDD.” From the outset, some women were so relieved to have their physical discomfort and unpleasant feelings recognized that they rushed to defend the label rather than asking for compassion and help that stopped short of diagnosing them as mentally ill. Research and clinical reports related to the premenstruum are extensive, but there is no proof that premenstrual mental illness exists. In a brilliant 1992 study, Sheryle Gallant and her colleagues took the symptoms listed for PMDD – then called Late Luteal Phase Dysphoric Disorder (LLPDD) in the 1987 edition of DSM – and asked three groups of people to document every day for two months the symptoms they experienced. The groups were women who reported severe premenstrual problems, women who reported no such problems, and men. The answers did not differ among the three groups. Circumventing the System The first inclusion of PMDD in DSM was controversial and achieved in a disingenuous way. The American Psychiatric Association, noting a massive protest at the 1986 conference of the Association for Women in Psychology that led to petitions and letters from individuals and organizations representing more than six million people, initially suggested leaving PMDD out. But Robert Spitzer, head psychiatrist of the 1987 edition (DSM-III-R), proposed what he called a compromise: The category would go in a specially created appendix "for categories requiring further study." Since the manual’s main text is supposedly based on scientific research, it seemed a victory for women that the label was given only provisional status. But once DSM-III-R was published, three things became clear. One, in the appendix, PMDD was given a fivedigit code, a title, a list of symptoms and a cutoff point (patients must have a specified number of symptoms to qualify for the label), exactly like the categories in the main text. Two, the appendix did not warn clinicians to avoid applying the label to patients. And three, the category was listed in the main text (under Mood Disorders), despite the APA’s claims that it was not. Seven years later, the 1994 edition (DSM-IV) followed similarly extraordinary procedures to include PMDD. In the early 1990s, the LLPDD subcommittee had assembled a massive literature review in which they concluded that (1) very little research supported the existence of such a thing as a premenstrual mental illness (in contrast to PMS); and (2) the relevant research was preliminary and methodologically flawed. Nonetheless, the subcommittee reported to Allen Francis, who led the work on DSM-IV, that they could not reach consensus about whether or not LLPDD should go in the manual. Francis then chose two other people to make the final recommendation, but concealed their identities from the media and the public for months. Then DSM officials announced that the category (now called PMDD) would "continue" to be listed "only" in the provisional appendix. When DSM-IV appeared, sure enough, PMDD was not only in the appendix but also in the main text, now under "Depressive Disorders." Was it coincidence that A. John Rush, a specialist in depression, was one of the two people chosen to make the final recommendation? And one has to wonder why PMDD ended up in this category, since women need not be depressed in order to meet its criteria (one need only have a single mood symptom – “marked” depression, anxiety, anger or lability, plus four physical symptoms). A strange collection of symptoms for an alleged mental illness. In addition, some members of the LLPDD subcommittee, including myself, were never notified of meeting dates nor given crucial information and data the subcommittee possessed. Nor was our feedback solicited until after the deadlines had passed. (After the publication of DSM-III-R, I had contacted Allen Francis and offered to send him the reviews that my students and I planned to write. He invited me to join the subcommittee, assuring me that "this time" decisions about the manual would be based on scientific evidence.) Denial and “Science” From the beginning, the only recommended psychiatric therapy for PMDD has been antidepressants, usually fluoexetine (Prozac). Although dietary and exercise changes or participation in self-help groups are sometimes recommended, the big push has been for drugs. Despite documentation that this diagnostic label has harmed women, from childcustody challenges to increased depression, LLPDD subcommittee chair Judith Gold has publicly denied reports of harm. In June 1999, with the patent on Prozac about to expire, its manufacturer, Eli Lilly & Co., organized a roundtable discussion attended by many of the PMDD subcommittee members. Getting Prozac approved for a different “mental illness” would give new life to the patent – explaining why Lilly needed to insist that PMDD is a real condition. Shortly afterward, an article called "Is Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder a Distinct Clinical Entity?" in the Journal of Women's Health and Gender-Based Medicine was presented as the state-of-the-science result of that roundtable. Presumably recalling their own description of pre-DSM-IV research as sparse and poor, the authors claimed that later evidence proved PMDD to be real and Prozac to be an effective treatment. But only a tiny number of the articles cited were truly post-DSM-IV research, and those provided no evidence that a premenstrual mental illness exists. A huge chunk of the article constituted a promotion of Prozac, by reporting that Prozac improves symptoms of women with PMDD. Certainly, if you give Prozac to any group of depressed or upset people, some will feel better. But that reveals nothing about the causes of their upset and, in this case, doesn’t prove the upset is related to menstrual cycle changes. The FDA’s Psychopharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC) met on November 3, 1999. There, representatives of Eli Lilly & Co. brought PMDD subcommittee member Jean Endicott, first author of the roundtable paper, to speak. According to the minutes, "There was consensus among [PDAC] committee members that PMDD is a recognized clinical entity that is well-defined and has accepted diagnostic criteria." The PDAC voted "yes" unanimously on the question, "Has the sponsor provided evidence from more than one adequate and well controlled clinical investigation that supports the conclusion that Fluoxetine is effective for the treatment of Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder?" It's hard to imagine what the outcome of that vote might have been without the assistance of Dr. Endicott and the roundtable article. A Profitable Motive Why was the FDA’s decision bad for women? First, Sarafem is Prozac. Many women prescribed Sarafem won’t know that and might not choose to take a mind-altering drug if they did know. Second, Prozac has side effects. By associating its use with PMS, Lilly hopes to broaden its use to millions of women, many of whom will not benefit from the drug. Side effects such as digestive and sleep problems and sexual dysfunction might be acceptable to women with depression, but they are completely unnecessary in women whose only complaints are physical discomforts associated with premenstrual syndrome. Other, safer options exist for women with troublesome PMS, including calcium supplementation, exercise and dietary changes. The decision to accept Lilly’s description of Sarafem as effective for “PMDD” exacerbates the misleading and dangerous assumption that this condition even exists. The first Sarafem commercial, which showed a woman frantic because she couldn't extract a shopping cart from a row of carts, included a voiceover warning women that they might think they have PMS when they really have PMDD. This ad was quickly taken off the air. One might have assumed it was removed because women found it offensive. Not true. According to an article in Drug Marketing, it was removed because the FDA took Lilly to task for supposedly trivializing the seriousness of this nonexistent disorder. The problem with PMDD is not the women who complain of premenstrual emotional problems but the diagnosis of PMDD itself. Excellent research shows that these women are significantly more likely than other women to be in upsetting life situations, such as being battered or being mistreated at work. To label them mentally disordered – to send the message that their problems are individual, psychological ones – hides the real, external sources of their trouble. The creation of Sarafem has extended Lilly’s patent on Prozac by seven years, adding untold millions to its bottom line. This is an example of a company taking cynical advantage of the legal and regulatory system to increase its profits at the expense of women’s health. Paula J. Caplan, Ph.D. (Paula_Caplan@Brown.edu), is an Affiliated Scholar at Brown University’s Pembroke Center for Research and Teaching on Women. References Caplan PJ, They Say You're Crazy: How the World's Most Powerful Psychiatrists Decide Who's Normal, 1995. Addison Wesley, Reading, MA. Endicott J, et al. “Is Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder a Distinct Clinical Entity?” Journal of Women's Health and Gender-Based Medicine 1999; 8(5):663-79. Gallant S, Popiel D, Hoffman D, Chakraborty P and Hamilton J. “Using daily ratings to confirm Premenstrual Syndrome/Late Luteal Phase Dysphoric Disorder. Part II. What makes a ‘real’ difference?” Psychosomatic Medicine 1992; 54, 167-81. SIDEBAR (if there’s room) Paula J. Caplan will lead a workshop on strategies for responding to the PMDD/Sarafem matter on June 8, at the Society for Menstrual Cycle Research Conference in Avon, Connecticut. She welcomes suggestions at Paula_Caplan@Brown.edu. For information about the conference, contact Joan Chrisler at jcchr@conncoll.edu.