(ECD) Programs - University of Alberta

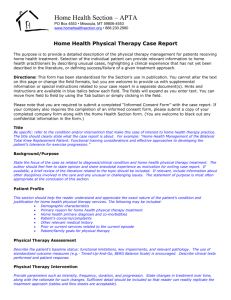

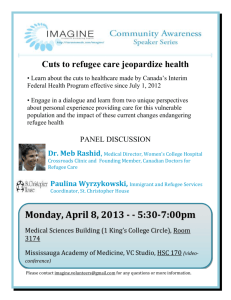

advertisement