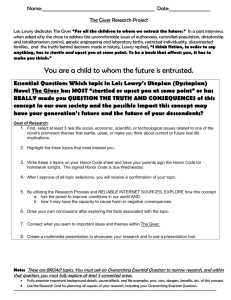

utopian societies - Dorman-Data

advertisement

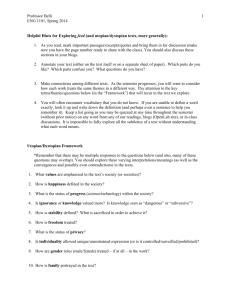

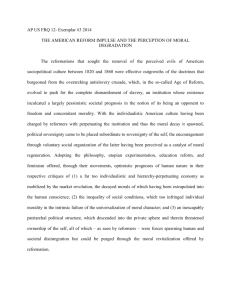

utopian societies The definition of utopia is an imaginary, perfect community. Coined by humanist Sir Thomas More in 1516, the word literally means "no place." European authors from the 16th to 19th centuries envisioned a variety of utopian communities, yet most remained in the realm of literature. The New World, however, witnessed widespread attempts to establish actual utopian societies. Ever since the first European immigrants traveled to North America, many people have viewed it as the ideal locale for implementing a particular vision of the perfect society. First, there was comparatively greater freedom of religion and speech in America than in the rest of the world. In addition, there was ample space for communities to isolate themselves from mainstream society. Nevertheless, although some groups, like the Puritans who settled in Massachusetts, met with significant success, most other utopian experiments met with failure. American utopian societies have been quite varied in their beliefs and practices. However, all dissociated themselves from mainstream society and rejected the idea of working within the existing social system for reform. Instead, members tried to create their own perfect societies, isolated from others, by experimenting with different forms of social organization. Generally, utopians believed they were pathfinders, moving into a future that would be better than either the past or the present. Most focused on improving spiritual practice while also transforming moral, social, and often economic relationships among individuals. In the search for perfection, however, most utopian groups were plagued by internal factionalism, as well as derision and hostility from the outside world. Utopian societies came in waves. The first wave began in 1663, when Dutch Mennonites settled near Lewes, Delaware and established the first communitarian settlement in North America in an effort to focus on their religious beliefs and practices. The English, however, destroyed the community in 1664 during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. Dozens of other utopian communities, based on a wide range of religious principles, followed the Mennonite settlement during the succeeding century. With abundant land and sparse settlement, those groups were able to exist in almost complete isolation from others, although some groups traveled extensively to bring converts to their settlements. The Shakers were the most successful utopian group during this period. Beginning in 1774, Mother Ann Lee led the Shakers in America. Lee believed that Jesus Christ had revealed himself to her to tell her that at the time of the Second Coming, Jesus would take a female form. Lee also taught that individuals must abstain from sexual intercourse. Although Shakers did travel to convert others, they largely kept to themselves in a number of agricultural-artisan communities. The Shakers are often seen as the most successful communitarian society, as there are still two Shaker communes in existence today. The second wave of utopian societies occurred in the first half of the 19th century. Those communities were often associated with the rise in reform movements that occurred during the Second Great Awakening. Many people also sought religious guidance or alternative living situations because of the tremendous changes wrought by the Industrial Revolution. As religious utopian societies flourished, so too did secular utopian communities, many of which condoned more interaction with mainstream U.S. life than their religious counterparts. Among the leading secular utopians were two recent arrivals from Europe, British manufacturer Robert Owen and French philosopher Charles Fourier. Before coming to the United States, Owen had revolutionized factory work in England by improving the circumstances under which workers labored. Moreover, he believed that suffering and vice could be eliminated if social relationships were perfected in "Villages of Unity and Mutual Cooperation." Convinced of that potentiality, Owen founded a settlement in New Harmony, Indiana. New Harmony was a communal socialist village that tried to harmonize labor conditions according to the notion that cooperation rather than competition led to the development of a superior social system. Although the New Harmony community proved short-lived because of internal factionalism, it inspired many other utopian communities in the 1840s. Fourier also theorized about a cooperative society based on universal principles of harmony. He hypothesized that harmony could exist between the material universe, organic life, animal life, and human society. Fourier established elaborate rules for his utopian communities, which were called phalanxes. About 2,000 individuals would live in a vast communal building amidst an agricultural landscape. Work was assigned by one's talent and ability. Communal wealth provided essential needs. Fourier's ideas met with little acceptance in France, but they were well received in the United States in the 1840s. By 1850, 40 phalanxes had been established under his direction. Most proved unsuccessful, but Brook Farm in West Roxbury, Massachusetts and North American Phalanx at Red Bank, New Jersey became famous, despite their brief existence. Other utopian communities dotted the U.S. landscape during the first half of the 19th century. Fruitlands, for instance, was a Transcendentalist community led by famed educator and philosopher Bronson Alcott. The few individuals at Fruitlands tried to live by a broad range of Transcendental principles, which included a severe form of vegetarianism. Indeed, they not only tried to avoid using any animal byproducts or animals for labor, but they also believed that vegetables had souls that must be respected as well. As a result, they would only eat fruit or vegetables that were above ground and already separated from their host plant. For example, they would eat only apples that had fallen to the ground; they would never pick apples from a tree. Not surprisingly, Fruitlands struggled economically, and many members suffered from various stages of starvation, including Alcott's own wife and children. Fruitlands dissolved quickly in the face of such hardship. The impracticality of the community's beliefs had doomed it to failure. John Humphrey Noyes' community at Oneida, New York was the most controversial utopian community of the 19th century. Established in 1848, Oneida prospered under Noyes' leadership so that more than 200 members lived there by the 1870s. A farm, a sawmill, and factories for canning and for the manufacture of such goods as chains, suitcases, silverware, woolens, and silk thread comprised the major components of the community. The society operated democratically with all decisions made by consensus, but its economy was communistic, and members shared all resources. Alcohol and tobacco were strictly prohibited at Oneida, and traditional marriage was abandoned. In fact, the community attracted the most attention for its sexual practices, which included "complex marriages" of multiple partners. All of Oneida's principles derived from Noyes' interpretation of the Bible, which he outlined in a number of publications, including Bible Communism in 1848. Overall, Oneida constituted a radical social, economic, and religious community. Although the utopian purpose and guidelines declined in the late 19th century, the current town of Oneida and the Oneida Company, which sells tableware, is an offshoot of the original utopian society. The third wave of utopianism in the United States developed between the 1870s and 1890s, when widespread industrialization led to a great deal of dislocation for large numbers of struggling workers. Many of the more than 100 utopian communities that formed during this era held that socialism, cooperation, or brotherhood offered an approach to the labor conditions of the day that was superior to capitalistic competition. Because they rejected capitalism, most Americans found such societies particularly objectionable. Washington State in particular became home to a number of utopian communities, including the Puget Sound Co-operative Colony, the Equality Colony, Freeland, Burley Colony, and Home. The reputation of Washington for radical communities was so well known that in the mid-1930s, Postmaster General James A. Farley offered a toast while visiting Seattle: "To the forty-seven states and the soviet of Washington." The utopian communities there were all secular, and they renounced mainstream U.S. politics and capitalist economics by trying to live isolated, communal lives. These utopias stressed economic cooperation and practiced it with commonly owned land and a cooperative store. Ironically, though, Washington utopians often found themselves participating in the U.S. economy that they abhorred to improve their quality of life. Many earned proceeds from timber, farming, and real estate enterprises. Moreover, each community almost continually reorganized its structure to allow for greater individuality and freedom, as the members found a number of deficiencies with communal living. Only the anarchic Home lasted for very long, but it moved away from communal living after a short time. The radical utopias of Washington may not have lasted, but they likely helped to set the stage in the early 20th century for continued radical politics: Washington consistently registered more votes for Socialist Party candidates than virtually anywhere else in the United States. Other communities formed during the third stage of utopian development as well. Like the Washington communities, Kaweah, in California's Sierra Nevada region, protested the labor and economic system of the United States. Kaweah was built on cooperative principles, which appealed to the joiners, many of whom had grown weary of the labor movement. Although most utopian societies in this period were secular, some religious communes did exist. The Jewish group, Am Olam, founded New Odessa on the Oregon coast. This community consisted primarily of young Jewish intellectuals who ultimately proved unsuited to the rural life required of the colony. A politically active Christian commonwealth also formed in Georgia. Despite the widespread flirtation with socialist and communist principles among the utopian societies in the late 19th century, few accepted the basic precept of communism that class struggle was inevitable. Indeed, most worked to undermine class struggles and attempted to build cooperative commonwealths. The vast majority of those experiments proved unsuccessful. One study has shown that during the late 19th century, 25% of all utopian communities failed within one year, and 30% of the nonreligious utopias failed in the first year. The last wave of utopian organization in the United States occurred during the radical social upheaval of the 1960s and 1970s. At least 4,000 communes developed during this period, and total membership exceeded 250,000 individuals. Those utopian societies were part of the general counterculture movement that searched for an alternative to war and dependence on technology. Members flocked to communes to experiment with collective living and to achieve personal, often spiritual, fulfillment. The utopias of the 1960s and 1970s frequently invoked simplicity rather than the complications of materialism in their living experiments. They often practiced progressive environmentalism, including organic farming, in an attempt to leave little impact on the earth. Ernest Callenbach captured the vision of a more environmentally sustainable future in his 1975 utopian novel, Ecotopia, which posited a future in which Washington, Oregon, and California seceded from the United States to form an ecologically based society. Many of the utopian societies of the 1960s and 1970s also rejected traditional family structures, including marriage and monogamy. Like their predecessors, they were often isolated in rural areas. However, for the first time, urban utopias also arose, usually near universities and drawing heavily from disenchanted college students. Since the counterculture utopias of the 1960s and 1970s, other communal living arrangements have arisen but with great controversy and little common ground. Many, like David Koresh's Branch Davidians, who died after a months-long government stand-off in Waco, Texas in 1993, have been dubbed cults. It seems likely that utopian societies will continue to arise where individuals with similar criticisms about modern society gather to offer an agenda for reforming society. References: Bestor, Arthur, Backwoods Utopias: The Sectarian Origins and the Owenite Phase of Communitarian Socialism in America, 16631829, 1970; Carden, M. L., Oneida: Utopian Community to Modern Corporation, 1969; Hine, Robert V., California's Utopian Colonies, 1966; Holloway, Mark, Heavens on Earth: Utopian Communities in America, 1680-1880, 1966; Oved, Yaacov, Two Hundred Years of American Communes, 1988. "utopian societies." World History: The Modern Era. 2007. ABC-CLIO. 15 May 2007 <http://www.worldhistory.abc-clio.com>.