1) fordism: historical developments

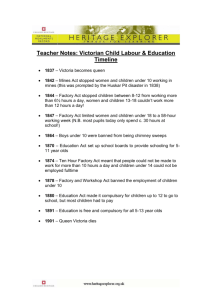

advertisement