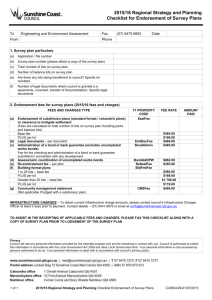

Cost recovery guidelines - Department of Treasury and Finance

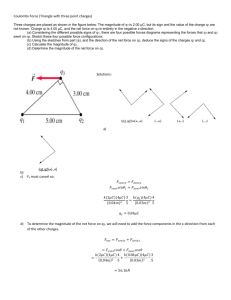

advertisement