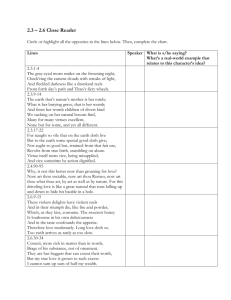

A MODEST PROPOSAL

advertisement