Family Structure Outcomes of Alternative Family Definitions

advertisement

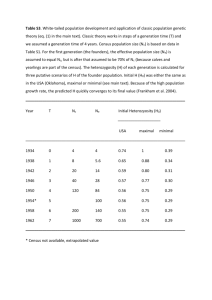

Family Structure Outcomes of Alternative Family Definitions Kathryn Harker Tillman* and Charles B. Nam Florida State University * This article is an original work by Kathryn Harker Tillman and Charles B. Nam, and is being submitted exclusively to PRPR for publication consideration. Please direct all correspondence to Kathryn Harker Tillman, Center for Demography and Population Health, Bellamy Building, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306-2270. Phone: 859-644-1669; Email: ktillman@fsu.edu. This paper is based on data from the Netherlands Kinship Panel Study (NKPS). We are grateful to the Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute (NIDI), Pearl Dykstra and the NKPS research team for providing us with access to the data and offering their valuable assistance and advice. We would also like to thank Karin L. Brewster and Suzanne M. Bianchi for their helpful comments on previous drafts of this paper, Abstract: Although the family continues to be a critical unit in demographic and social analysis, perceptions of what constitutes the “family” vary across groups and societies. The standard definition of the family used in U.S. censuses and surveys (persons related by blood, marriage, or adoption, and living in the same residence) may limit description and analysis of family structure. Yet, it is what determines official data on the family. Because information on alternative family definitions is not available for the U.S., we use data from the Netherlands Kinship Panel Study to assess the effect of three definitions on dimensions of the family. We find significant differences across the three definitions and by stages of the life cycle, and we discuss implications for our understanding of family structure and functions in the U.S. and elsewhere, and some policy and programmatic consequences. Key words: censuses, family definition, family size, family structure, demographic surveys 1 Introduction Although the family continues to be a critical unit of demographic and social analysis, perceptions of what constitutes the “family” vary across groups and societies. Often popular perceptions of what constitutes the family are driven by prevailing views regarding the kinds of functions that people in these units are expected to perform for one another and for society at large (e.g. economic and emotional support, reproduction, socialization of children, etc.). Depending on social norms and values, therefore, all of the following could be viewed as constituting a family unit: a married couple and their children living at home, two sisters living together, a single mother and her children living at home, a same-sex couple, a married couple and their children and grandchildren wherever they live, an unmarried cohabiting couple, a divorced couple neither of whom has remarried and their children, an extended kin network, and many other social groupings. Yet, popular perceptions of the family may not necessarily be in accord with formal definitions. Official governmental statistics on the family in the United States are based on a specific definition that may or may not capture varying views of the family. This has important implications for demographic researchers and policy makers, as it limits the ability to fully examine patterns of exchange, support and caregiving that affect the daily lives of individuals. The purpose of this article is to examine the implications of using alternative defining criteria for statistical portraits of the “family” as a social institution. We begin by specifying the standard definition of the family used in the United States and summarizing its evolution. We then consider alternative definitions of the family, selecting a limited number for comparison, and explore statistically the implications of using the various definitions of the family. Finally, 2 we briefly evaluate the findings in terms of their implications for demographic research on families and for policies and programs that are targeted at families and children. The Standard Definition of the Family To what extent do census and survey inquiries in the U.S. reflect the evolution and diversity of family groups? In the censuses of 1790 through 1840, the unit of enumeration was what we now regard as a household (persons occupying a common residence), although some publications refer to it as a family. Hareven and Vinovskis (1978) point out that historical studies of the U.S. in the nineteenth century tend to confuse the household and the family. From 1790 through 1840, only the heads of the unit were specified. Other members were counted, but no additional information about them was recorded (e.g., “two children” might be recorded). Beginning in 1850, the census adopted individual enumeration that identified each member of the household by name; however, relationships between members were not specified. The Census of 1880 was the first to indicate the relationship of each household member to the designated head. It would be sixty more years before a family, as distinguished from a household, was formerly defined and census statistics on the family provided. The U.S. Census Bureau adopted a definition of the family for use in the 1940 Census that has remained constant over time in its censuses and has been employed in most demographic surveys since that time. Regarded as the traditional definition, it treats the family as “a group of two people or more related by birth, marriage, or adoption and residing together; all such people are considered as members of one family” (Glick 1957; Casper & O’Connell 2000; Fields & Casper 2001). Since its adoption, this Census definition of the family has come to be used for a variety of official purposes. For example, statistical portraits of family change, the measurement 3 of poverty, and the determination of eligibility for many social programs now rely upon this definition. It is important to note, however, that the definition of the family was specified before the development of poverty measures or the establishment of these programs and has remained unchanged over time, despite major shifts in the kinds of living arrangements that are common in the United States. In recognition of the many different living arrangements found in the United States and in countries around the world, The United Nations (1997) has recommended that censuses consider the following guidelines when defining and measuring the family: “A family nucleus is one of the following types (each of which must consist of persons living in the same household): (a) a married couple without children, (b) a married couple with one or more unmarried children, (c) a father with one or more unmarried children, or (d) a mother with one or more unmarried children. Couples living in consensual unions should be regarded as married couples…The family nucleus does not include all family types, such as brothers or sisters living together without their offspring or parents, or an aunt living with a niece who has no child. It also excludes … a widowed parent living with her married son and his family” (p.67). Although few countries seem to observe all points of this recommendation, all countries that engage in census-taking appear to restrict the definition of family to individuals living in the same household. This restriction is due primarily to the use of distinct housing units as building blocks in census enumerations and as sampling elements in censuses. In general, it has been assumed that the household is the primary basis for the exchange of economic and social resources between family members. Furthermore, for both logistical and cost reasons, it has not 4 been possible in censuses to incorporate into the family unit those who might be considered family members but who live elsewhere (Taeuber & Taeuber 1971). Different countries have varied significantly in how closely they have followed the UN recommendations regarding who makes up a “couple” according to their census definitions of the family. For example, while the UN recommends treating couples in consensual unions (referred to elsewhere as common-law couples or cohabiters) as “married,” many countries, like the United States, do not do so (e.g., Argentina, Nicaragua, some Eastern European countries, most Islamic countries) (NGLS 2002). Many other countries consider heterosexuals in consensual unions to be “married,” but do not consider homosexual couples in this light (e.g., UK, France, Australia) (INSEE 1999; National Statistics 2001; Stratton 2002). These restrictions are changing, however, especially in Canada and throughout much of the European Union (NGLS 2002; Statistics Canada 2006), as cohabitation and homosexual marriage are becoming more normative and accepted practices. Some countries are also now considering the use of more than one definition of the family in their censuses. For example, the Census of Canada includes two family concepts – a census family and an economic family. A census family is defined as: “a married couple and the children, if any, of either or both spouses; a couple living common law and the children, if any, of either or both partners; or, a lone parent of any marital status with at least one child living in the same dwelling and that child or those children. All members of a particular census family live in the same dwelling. A couple may be of opposite or same sex. Children may be of birth, marriage or adoption regardless of their age or marital status as long as they live in the dwelling and do not have their own spouse or child living in the dwelling. Grandchildren living with their 5 grandparent(s) but with no parents present also constitute a census family” (Statistics Canada 2006). An economic family is defined as: “a group of two or more persons who live in the same dwelling and are related to each other by blood, marriage, common-law or adoption. A couple may be of opposite or same sex. Foster children are included…all persons who are members of a census family are also members of an economic family… two co-resident census families who are related to one another are considered one economic family…co-resident siblings who are not members of a census family are considered as one economic family.” (Statistics Canada 2006). A strength of having more than one official definition of the family is that researchers and statisticians are less limited in the range of research questions they can address or practical applications they can make with their data. The United States has not yet moved in this direction, however, and continues to hold a more narrow definition of the family than many other Western nations. Limitations of the Standard Definition of the Family By limiting the definition and measurement of family to include only co-residential relatives, demographic researchers and policy makers are constrained in their ability to fully examine patterns of exchange, support and care-giving that occur across households. One might argue that residential separation of family members prevents these family functions from operating effectively. Members may be separated by only a short distance, however, so that visiting is frequent and interaction is regular. Even in cases where residential separation involves 6 longer distances, the increasing availability of transportation, communication channels, and electronic financial transfers makes it possible to stay in contact with and provide support to family members in meaningful ways (Bane 1976; Knodel 2006). Moreover, shared residence does not guarantee shared family experiences. Even when family members live together, work schedules and life styles may inhibit meaningful contact between them, particularly when it comes to the provision of intimacy, emotional support or involvement in practical caregiving tasks (Cherlin 2005). While it is not feasible in censuses to incorporate into the family unit individuals who do not live in a shared residence, it is possible in social surveys to ask respondents about their relatives living elsewhere. Bonvalet (2003) used such an approach to define alternative family forms in France. The existence of “local family circles,” she points out, provides evidence that contradicts the notion of a decline of the family. A substantial minority of respondents interacted frequently with relatives who were not in the same residence but lived in the community, both through providing help and services and through conversations. Others were drawn to nonresidential family members because of economic need. To Bonvalet, this suggested an alternative family lifestyle, “which respects the independence of each individual and couple, and an adaptation of the complex family to urban society.” Similarly, surveys of elderly individuals in Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam have indicated that the majority of older persons who live in solitary households have a child living within the same locality or in a residence adjacent to theirs, and that those who have children living at farther distances are increasingly able to visit and to maintain contact via cell phones (Knodel 2006). A recent survey by the Pew Research Center also revealed that in the U.S.: 7 “…family members are staying in ever more frequent touch; that family remains the greatest source of satisfaction in people’s lives; that most parents and children live within an hour’s drive of one another . . . three-quarters of adults (73%) report that on an average day they speak with a family member who doesn’t live in their house, and nearly one-quarter (24%) say they have a meal with such a relative” (Pew Research Center 2006, p. 1). Thus, research shows that contact between non-resident family members is relatively high. This contact indicates the presence of social networks that could provide for the transfer of important resources across households. An additional factor that limits the scope of the standard census-based definition of the family concerns “rules of residence” (U.S. Bureau of the Census 2003; Prewitt 2005). These rules specify which members of a household who are not at home at the time of a census (or social survey) should be counted there and which should not. For example, in the United States Census, members of a family who are in military service are to be counted as residing where they serve rather than with their family living elsewhere. Likewise, unmarried college students are enumerated where they live in the college community instead of with their families. These and other rules of residence affect the constitution of the family unit and influence the statistical picture of the family. Finally, the standard definition of the family in the United States excludes adults living in consensual unions and the children of such relationships, despite the fact that these living arrangements are becoming increasingly common. Not only has there been a rise in the number of same-sex couples living together openly, nearly 6% of all households are now headed by adults living in cohabiting unions (U.S. Census Bureau 2003, 2004). Furthermore, 8 at least 5% of all children live in cohabiting families and 40% of all non-marital births occur to cohabiting couples (Raley 2001). Although there are differences between married and cohabiting individuals in terms of their money management strategies, research has indicated that cohabiting individuals tend to make substantial financial and social investments in their partners and the children who live with them (Bauman 1999; DeLeire & Kalil 2005; Kenney 2004; Stewart 2001). The exclusion of these individuals from our measures of the family automatically discounts the investments and resources that they bring to the family unit. Given the possible limitations of the standard census definition of the family, our goal is to examine the statistical implications of using alternative defining criteria for the “family”. While the standard definition may be entirely appropriate for certain purposes, we believe that the incorporation of additional measures of “family” into social surveys could prove useful and informative. If we wish to understand the structure and functioning of families, we must first develop definitions of “family” that adequately tap into the everyday experiences of individuals. The range of possible family definitions is great; therefore, our selections are intended to be illustrative and not exhaustive. We develop three different definitions of the family – one that is standard and residence-based, one that expands the standard residence-based definition to include cohabiting partners and their children, and one that goes beyond the second definition to include non-resident spouses and children wherever they reside. Data Family data can be constructed from two other sources than a census: genealogical records and demographic surveys. Genealogical records, or family histories, permit a researcher to consider various family forms. Access to large genealogical datasets allow for analysis using 9 alternative family definitions (Finnegan & Drake 1994; Gavrilov et al. 2002; Smith & Mineau 2003; Nam 2005). Sample surveys that are keyed to individuals rather than to households likewise could provide for questions that solicit information about family members living at other residences. Yet, most demographic surveys are household-based and include only the standard family definition. One recent exception is the Netherlands Kinship Panel Study (Dykstra et al. 2005; Dykstra 1999; Dykstra & Komter 2004), which we use for our data analyses. The NKPS allows examination of family and kinship from a dynamic multi-actor perspective. It identifies an “anchor’ person from a random sample of individuals between age 18 and 79 within private households, and includes information gathered from that person, a spouse or cohabiting partner, a maximum of one parent, a maximum of two children aged 15 and over, and up to one sibling aged 15 and over. Although some information was obtained about grandparents and grandchildren, they were not interviewed. A second stratified random sample of members of the four largest in-migrant groups – Turks, Moroccans, Surinamese, and Dutch Antilleans – was added to the study. Between October 2002 and January 2004, a total of over 11,000 face-to-face interviews were conducted using a computer assisted personal interview (CAPI) questionnaire. At the time of the interview, respondents also received a self-completion questionnaire that was collected at a later date. In 90 percent of the cases the self-completion questionnaire was returned and processed. A second wave of the survey has since been conducted. The overall response rate of the NKPS study was 45 percent, which is comparable to the response rates generally achieved in the Netherlands. Response rates were lowest in the most urbanized regions, for men in the youngest age categories living with their parents, and for women living alone (Dykstra et al. 2005). 10 We acquired access to the main sample of the first wave data. With the exclusion of the second sample of in-migrant groups, our descriptive analyses include data from a total of 8,151 respondents. Methods As stated above, we develop three different definitions of the family. The Standard Residence-Based Definition defines as family members only those people who are related by blood, marriage or adoption and who are residing together. The Expanded Residence-Based Definition expands upon the previous definition of the family to include cohabiting partners and their children. The Broader Non-Residence-Based Definition expands the definition of the family even farther to include non-resident spouses and children wherever they reside. We then examine how the specific definition used affects our understanding of family characteristics. For each definition of the family, we provide descriptive statistics regarding the number of family units (and the percentage of the sample living in a “family” unit), the percentage of the sample living in the various family types (e.g. percentage of “single” adults), average family size, average number of children, average age of children, and proximity of children. We then discuss the implications of the findings, paying particular attention to how the descriptive statistics differ by stages of the life cycle. Findings How does our understanding of the family as a demographic unit change as the criteria for defining the family change? Table 1 summarizes these differences across the three specified family definitions in the full sample (all differences described are statistically significant). 11 Proportions of household heads who are female and the average age of household heads are common across the three definitions. The standard residence-based definition, however, does not recognize cohabiting partners as family members. Thus, the proportion of respondents categorized as “single – never married” and “single – divorced/separated” is significantly higher when the traditional definition is used (0.30 and 0.07, respectively) than when the definition of family is expanded to include cohabiters (0.20 and 0.06, respectively). Overall, 12 percent of the respondents report cohabiting with a partner. <<Table 1 About Here>> In addition to the fact that the standard definition of the family in the U.S. does not recognize cohabiters as family members, few demographic studies describe the families of samesex couples. Of our sample of 8,151 respondents, 5,248 live with another adult as a couple (spouse/partner). Of those, 57 are men living with another man and 72 are women living with another woman. Of the whole sample, 1.6% can be identified as living in homosexual unions (0.7 percent gay and 0.9 percent lesbian), with approximately half of that group living in married unions and the other half living in cohabiting unions.1 Of the 5,248 respondents living in twoadult unions, 2.5 percent are in homosexual unions. It is obvious that expanding the definition of a family will increase the number of family units discovered for a sample of individuals. We count 5,380 families (comprising 66 percent of the respondents) when the standard residence-based definition is used. The number of families increases to 5,973 (or 73 percent of the sample) when cohabiters are included. When the broadest definition (irrespective of residence) is used, there are 6,894 families (or 85 percent of 1 Same-sex marriage was legalized in the Netherlands in 2001. Recent statistics indicate that approximately 1,100 to 1,200 same-sex couples are now married each year (Statistics Netherlands 2006). 12 the sample). Using the broader definition instead of the standard definition expands the number of families by 28 percent. Significant differences in family size arise when we employ the different definitions of a family. Average family size increases significantly when cohabiters and their resident children are included as family members, and again with the inclusion of all non-resident spouses and children under our broadest definition of a family. Mean family size stands at 2.57 when the traditional definition is used, 2.71 when cohabiters and their children are added, and 3.63 when the broadest definition is used. The child component of the average family size moves from 0.73 in the first case, to 0.75 in the second, and 1.67 in the third. Thus, the average respondent has more children living outside of the home than inside of the home. The broadest definition also results in a much higher average age of children, reflecting the older average age of the parents from whom they are living apart. In addition, we were able to specify the geographical proximity of children to respondents. Of the 5,708 respondents having children, 42 percent had all children living in the home. Twenty-one percent had children living outside the home but within the municipality; 15 percent had children living outside the municipality but within the province; and 22 percent had children who lived outside the province.2 Because the Netherlands is a fairly compact country geographically, a substantial proportion of children living away from home could visit frequently. Figure 1 elaborates family size comparisons for the standard definition (which we have labeled “Resident Family Size”) and the broadest one (labeled “Total Family Size”), specific to 2 A Dutch province represents the administrative layer in between the national government and the local municipalities, having the responsibility for matters of sub-national or regional importance. There are currently 12 provinces, ranging in size from approximately 520 square miles to 1900 square miles. All provinces of the Netherlands are further divided into municipalities, administrative local areas, of which there are 458 (Overheid.nl 2006; World Gazetteer 2006). 13 marital status and child presence categories. There is a family size difference of one person between these two definitions, using the full sample. Comparing the two family alternatives using data only for respondents who are married without children in the home increases the difference to two persons. Average family size changes from 4.0 to 4.5 when the definitions are compared for two married adults with children in the home. Overall, the difference is greater than two persons for unmarried or cohabiting adults (i.e., “Single” adults) without children in the residence, as these individuals would not be considered to be a part of a family by the standard definition, and approximately one person for unmarried or cohabiting adults with children in the residence. <<Figure 1 About Here>> The arrows on the figure indicate where we have disaggregated the traditional definition’s “Single” adult category into separate categories representing one adult (with or without children) and two cohabiting adults (with or without children). The results presented here illustrate that important differences in family size are obscured when these groups of people are categorized together, as they generally are under the standard definition of the family. For example, for cohabiters with children in the residence, there is a family size difference of almost two persons when non-resident family members are included in the count. For adults living alone with children in the residence, however, there is a family size difference of only 0.7 persons. Because children are more likely to leave home as they age (often to attend school, take a job elsewhere, start their own families, or live with other relatives) and marital partners may be more likely to occupy separate living quarters (usually for work or long-term care reasons) as the marriage endures, changes in family size can be expected across the life cycle. Figure 2 shows 14 that pattern for four age categories. When the household head is less than or equal to 30 years of age, the two definitions produce an average family size difference of only 0.3. In the 31 to 45 year age range, the 0.3 difference is maintained. By ages 46 to 60 years of age, the average family size difference expands to 1.3. Beyond age 60, the traditional definition leads to an average family size of 1.8, whereas the broader definition results in a family size of 4.4. Almost all of this significant difference in family size is the result of the broader definition’s ability to capture non-resident children, as opposed to non-resident spouses (results not shown, but available upon request). <<Figure 2 About Here>> Figure 3 highlights the average age of children under the two definitions. The mean age of the youngest child under the standard definition of a family (co-resident child related by blood, marriage or adoption) is 10.4 years, while the mean age of the youngest non-resident child is 29.3 years. Overall, the mean age of the youngest child under the broadest definition of a family is 19.2 years. Comparably, the mean age of the oldest child when the standard definition is used is 13.3 years, the mean age of the oldest non-resident child is 33.3 years, and the mean age of the oldest child using the broadest definition of a family is 23.6 years. <<Figure 3 About Here>> Discussion and Conclusions The standard definition of the family used in many censuses and demographic surveys restricts the family unit to persons related by birth, marriage, or adoption and living in the same residence. Contemporary views of the family recognize a variety of family forms, some of which require a more extensive definition of the family. In particular, common residence no 15 longer seems to be a qualification for describing a family unit. Many family functions and forms of interaction take place among related persons who do not live together (Bane 1976; Bonvalet 2003; Knodel 2006; Pew Research Center 2006). Conversely, it is sometimes the case that related persons living together are not involved in critical family functions or interactions. Moreover, couples united without marriage generally perform the same functions as married couples, and in many cases have children of their own. Under the standard U.S. definition, they are not treated as members of a family. Our intent was to consider alternative definitions of the family and to indicate their implications for statistical descriptions of family structure and family characteristics. Using data from a Dutch kinship survey, we were able to compare the statistical portrait of Dutch family life based on the standard U.S. Census definition with two alternatives. We find, not surprisingly, that a more inclusive definition of “family” yields both a greater count of families and a larger mean family size. Further, the number of single adults dropped. More importantly, we observed that the disparities increased over the family life cycle, as family members aged. We believe that these findings from the Netherlands are useful for understanding how employing different definitions of the family might also lead to the observation of different family structure outcomes in the U.S. Although cohabitation is less common in the United States than in the Netherlands, Census data from the U.S. indicate that a significant percentage of households are at any given time headed by adults living in cohabiting unions (nearly 6 percent), and approximately 1.0 percent of all households are headed by those in cohabiting same-sex unions (U.S. Census Bureau 2003, 2004) (See Table 2). By broadening the definition of family to include cohabiting couples and their children, U.S. researchers would also count more families and find larger family sizes than they do when using the standard definition of the family. Given 16 past research that indicates that cohabitors tend to make substantial investments in their partners and/or children, it may be appropriate for researchers interested in studying the structure and functioning of residential family units (or simply in tallying the number of residential families in the U.S.) to consider adopting an expanded residence-based definition. <<Table 2 About Here>> As in the Netherlands, co-residence between adult children and their parents is not the norm in the U.S. Thus, we expect that if U.S. researchers were to expand the definition of family to include family members living in other households they would also find larger families. Furthermore, the disparities in family size, as compared to those calculated when using the standard definition of family, would also become wider as the age of household heads increases. For researchers interested in studying the composition of family networks and support systems, the adoption of a broader non-residence-based definition may be appropriate. Does using an alternative definition of a family have meaningful consequences beyond affecting the size, composition, and characteristics of family units? Does it have an impact on policies or programs carried out by public and private organizations? We examine two such potential impacts. How many families are estimated to be living in poverty has been much-debated for decades. In 1965, Orshansky developed a formula for calculating poverty thresholds. It was based on an economy food plan for a family of four, adjusted for families of different size and farm/non-farm status and tied to the average percentage of money income families spent on food. This formula essentially remains the basis for presenting poverty statistics, although the formula has been adjusted over the years to take account of variations in food budgets and types of income and in revisions of the percentage of money income spent on food (Fisher 1992; Iceland 17 2004). In recent years, the Census Bureau has also published poverty statistics based on alternative criteria. Although evaluations of the adequacy of poverty measurement have considered the validity and reliability of food budgets and income patterns, little attention has been given to the import of applying the formula to a standard family definition in order to determine the estimated number of families (or persons) in need. A committee of the National Academy of Sciences (Citro & Michael 1995), in reviewing poverty measurement and its weaknesses, did propose including cohabiting couples in the calculation and giving consideration to the income contribution of non-family household members and to the use of income equivalence scales for families. These proposals have not been implemented. The use of family definitions that would add to the number of families (e.g., giving family status to cohabiting couples and to persons living alone but with a spouse and/or children not in the same residence) would surely affect the poverty rate. To measure the impact on poverty estimation, additional income (or lack of income) brought to the family unit when another person is included would have to be balanced with the change in family size and composition, as well as an estimation of the extent to which resources are shared between members. For some family units, the addition of new members would lead to a net increase in income, while for others it would lead to a net decrease. For example, Carlson and Danziger (1999) have found that including cohabiters’ contributions in calculations of family income would lower the child poverty rate by approximately 3 percent. It is less clear how the inclusion of the financial contributions of non-resident family members might affect poverty rates or the experience of economic hardship. In any event, however, defining the family differently would lead to altered figures on the extent of poverty experienced in the United States (Bauman 1999; 18 Carlson & Danziger 1999). Moreover, the effect of altering estimates of poverty would likely be multiplied, because poverty guidelines (a variant of poverty thresholds calculated by the Census Bureau) are used by the Federal Government in determining eligibility for numerous programs, including Head Start, Food Stamps, the National School Lunch Program, Home Energy Assistance, and Children’s Health Insurance. Another area in which alternative definitions of the family would have an impact is on policies and programs related to persons at older ages. Our analysis shows that the impact of various family definitions increases with age of household head and is especially sharp where the head is 45 years or older. In this older age bracket, the original family has tended to disperse residentially. Yet, children who have left home may be contributing financial and social support to their parents or, conversely, the parents may still be providing assistance to their children or grandchildren. It should not be assumed that living alone during the elder years is a sign of weak family relationships or a lack of financial and practical support between family members (Knodel 2006). Previous research has shown that contact between non-resident family members is relatively high (Bonvalet 2003; Bane 1976; Knodel 2006). In the NKPS, respondents were asked about the sharing of specific practical, emotional, and financial resources with non-resident children. This information was obtained for up to two randomly chosen non-resident children (either biological or adopted) who were aged 15 or older at the time of the interview. While the information obtained does not necessarily reflect overall levels of assistance given to or received from all non-resident children (or any other non-resident family members), our analysis of the data suggests that the sharing of resources across households is quite common. Furthermore, we 19 find that respondents tend to provide more housework and practical help, financial resources, and advice to their non-resident children than they receive in return (See Table 3). <<Table 3 About Here>> This pattern appears to hold across the lifespan, even among those in the oldest age group (over 60 years of age). For example, at least a quarter of individuals with non-resident children, regardless of age, have provided a child with substantial financial help or given them gifts of substantial financial value within the past twelve months. Only about three to four percent of all respondents, however, have received substantial financial help or gifts from their non-resident children. Similarly, 84.5 percent of respondents have provided advice or counsel, 56.7 percent have provided practical help, and 39.9 percent have provided housework help to a non-resident child within the last three months. In return, however, only 67.9 percent, 44.5 percent, and 28.2 percent of respondents have received help with advice, practical matters or housework, respectively, from non-resident children. A greater recognition of the enduring ties between parents and children, in particular the continuing flow of financial and social resources from older parents to adult non-resident children, could alter our understanding of the material and emotional well-being of older persons. Even if one accepts the idea that the standard definition of the family is inadequate to serve a wide variety of research interests and some additional definitions are needed, there remains the question of which among many possible definitions should be adopted by demographic researchers. Our analysis presents only two alternatives for illustrative purposes. We intend to use the same data source to examine other alternative definitions and assess the consequences for indicators of family structure. 20 Ultimately, we hope to be able to conduct similar analyses with data from the United States. We urge the U.S. Census Bureau to collect the necessary information to do so, initially on an experimental basis, through one of its surveys. Some new questions asked of householders in the supplement to the Current Population Survey dealing with families would begin to enable some alternative family definitions and would permit some indications of the impact on family structure. Subsequently, consideration can be given to a survey mechanism similar to that of the Netherlands Kinship Panel Survey that can provide a more extensive and clearer picture of family life in America. 21 References Bane, M.J. (1976). Here to Stay: American Families in the Twentieth Century. New York: Basic Books. Bauman, K.J. (1999). Shifting Family Definitions: The effect of cohabitation and other nonfamily household relationships on measures of poverty. Demography. 36(3): 315-325. Bonvalet, C. (2003). The Local Family Circle. Population. 58(1): 9-42. Carlson, M. & Danziger, S. (1999). Cohabitation and the Measurement of Child Poverty. Review of Income and Wealth. 45(2): 179-191. Casper, L. & O’Connell, M. (2000). Family and Household Composition of the Population. pp. 210-213, in: M. J. Anderson (ed.), Encyclopedia of the U.S. Census. Washington: CQ Press. Cherlin, A. (2005). Public and Private Families, 4th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. Citro, C.F. & Michael, R.T. (eds.). (1995). Measuring Poverty: a New Approach. Washington: National Academy Press. DeLeire, T. & Kalil, A. (2005). How Do Cohabiting Couples With Children Spend Money? Journal of Marriage and Family. 67: 286-295. Dykstra, P. (1999). Netherlands Kinship Panel Study; a Multi-Actor, Multi-Method Panel Survey on Solidarity in Family Relationships. http://www.nkps.nl/NKPSEN/nkps.htm. Dykstra, P. & Komter, A.E. (2004). Structural characteristics of Dutch kinship networks. Unpublished paper. Dykstra, P., Kalmijn, M., Knijn, T.C.M., Komter, A.E., Liefbroer, A.C. & Mulder, C.H. (2005). Codebook of the Netherlands Kinship Panel Study. http://www.nkps.nl/NKPSEN/nkps.htm. 22 Fields, J.& Casper, L. (2001). America’s Families and Living Arrangements. Current Population Reports, Series P-20, no. 537. Finnegan, R. & Drake, M. (1994). From Family Tree to Family History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Fisher, G.M. (1992). The Development and History of the Poverty Thresholds. Social Security Bulletin 33(4): 3-14. Gavrilov, L.A., Gavrilov, N.S., Olshansky, S.J. & Carnes, B.A. (2002). Genealogical Data and the Biodemography of Human Longevity. Social Biology 49: 160-173. Glick, P.C. (1957). American Families. New York: John Wiley. Hareven, T.K. & Vinovskis, M.A.. (1978). Family and Population in Nineteenth-Century America. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Iceland, John. 2004. Poverty in America: A Handbook. Berkeley, CA: University of California. INSEE. 1999. French Population Census, March 1999. http://www.recensement.insee.fr/RP99/rp99/pae_accueil.paccueil Kenney, C. (2004). Cohabiting Couple, Filing Jointly? Resource pooling and U.S. poverty policies. Family Relations 53: 237-247. Knodel, J. (2006). Review of United Nations Population Division’s “Living Arrangements of Older Persons Around the World”. Population and Development Review 32: 373-375. Nam, C.B. (2005). The Concept of the Family: Demographic and Genealogical Perspectives. Sociation Today 2(2): 1-8. National Statistics. (2001). Census 2001 – Families of England and Wales. http://www.statistics.gov.uk/census2001/profiles/commentaries/family.asp 23 NGLS (U.N. Non-Governmental Liaison Service). (2002). Roundup. http://www.un-ngls.org/documents/pdf/roundup/ru92kids.pdf Orshansky, M. (1965). Counting the Poor: Another Look at the Poverty Profile. Social Security Bulletin 28(1): 3-29. Overheid.nl. (2006). About the Dutch Government. http://www.overheid.nl/guest/aboutgov/. Pew Research Center. (2006). Families Drawn Together by Communication Revolution: A Social Trends Report. http://pewresearch.org. Prewitt, K. (2005). Politics and Science in Census Taking, in: R. Farley & J. Haaga (eds.), The American People: Census 2000. New York: Russell Sage. Raley, R.K. (2001). Increasing Fertility in Cohabiting Unions: Evidence for the Second Demographic Transition in the United States? Demography 38(1): 59-66. Smith, K.R. & Mineau, G.P. (2003). Genealogical Records, in: P. Demeny & G. McNicholl (eds.), Encyclopedia of Population. New York: Macmillan. Statistics Canada. (2006). Census of Canada. http://www12.statcan.ca/English/census01/home/index.cfm Statistics Netherlands. (2006). Zoekresultaten. http://www.cbs.nl/en-GB/menu/_unique/ search/default.htm?querytxt=same%20sex%20marriage&searchmode=free Stewart, S.D. (2001). Contemporary American Stepparenthood: Integrating Cohabiting and Nonresident Stepparents. Population Research and Policy Review 20: 345-364. Stratton, M. (2002). Understanding Family Data – 2001 Census of Population and Housing. Paper presented at the Australian Population Association Conference. Sydney, Australia. http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/c311215.nsf/0/ 77F742BC09070CD7 CA256E1008348 61?Open 24 Taeuber, C. & Taeuber, I.B. (1971). People of the United States in the 20th Century. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office. United Nations. (1997). Principles and Recommendations for Population and Housing Censuses. Statistical Papers, Series M, no. 67/Rev.1. U.S. Census Bureau. (2004). American FactFinder: 2004 American Community Survey. http://factfinder.census.gov U.S. Census Bureau. (2003). Married-Couple and Unmarried-Couple Partner Households: 2000. Census 2000 Special Reports. http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/censr-5.pdf World Gazetteer. (2006). Netherlands: Administrative Divisions (population and area). http://www.world-gazetteer.com/r/r_nl.htm 20 Table 1: Means and Standard Deviations of Respondents' Family Characteristics, Full Sample (N=8151) Using a Standard (Census-like) Residence-Based Definition of Family Using an Expanded ResidenceBased Defintion of Family (w/Cohab) Using a Broader Non-ResidenceBased Definition of Family Family Characteristics Mean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev. Sex of Household Head (Female) Age of Household Head (Years) Age of household heads with children (n=5708) Age of household heads with no children (n=2443) 0.14 45.78 51.75 33.50 0.34 15.99 13.34 13.84 0.14 45.78 51.75 33.50 0.34 15.99 13.34 13.84 0.14 45.78 51.75 33.50 0.34 15.99 13.34 13.84 Respondent Married Heterosexual Marriage Homosexual Marriage Respondent Cohabiting Heterosexual Cohabitation Homosexual Cohabitation Respondent Single - Never Married Respondent Single - Divorced/Separated Respondent Single - Widowed 0.58 ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ 0.30 0.07 0.05 0.49 ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ 0.46 0.26 0.22 0.58 0.57 0.01 0.12 0.11 0.01 0.20 0.06 0.05 0.49 0.10 0.10 0.32 0.08 0.08 0.40 0.23 0.21 0.58 0.57 0.01 0.12 0.11 0.01 0.20 0.06 0.05 0.49 0.10 0.10 0.32 0.08 0.08 0.40 0.23 0.21 5380 (66%) 2.74 2.57 ~ ~ 1.40 1.45 ~ 5973 (73%) 2.74 2.71 ~ ~ 1.40 1.39 ~ ^ 6894 (85%) 2.74 2.71 3.63 ~ 1.40 1.39 1.66 ^, # Number of Children in Resident Family Total Number of Biological/Adopted Children Total Number of Step-Children and Partners' Children Total Number of Children (Bio/Adopted/Step/Partners') 0.73 ~ ~ ~ 1.11 ~ ~ ~ 0.75 ~ ~ ~ 1.12 ~ ~ ~ ^ 0.75 1.39 0.28 1.67 1.12 1.49 0.84 1.54 ^ ^, # ^, # ^, # Age of Youngest Child in Household (R's with children in home, n=3103) Age of Oldest Child in Household (R's with children in home, n=3103) Age of Youngest Non-resident Child (R's with non-resident children, n=3297) Age of Oldest Non-resident Child (R's with non-resident children, n=3297) Age of Youngest Child (R's with children, n=5708) Age of Oldest Child (R's with children, n=5708) 10.44 13.25 ~ ~ ~ ~ 8.63 8.53 ~ ~ ~ ~ 10.44 13.25 ~ ~ ~ ~ 8.63 8.53 ~ ~ ~ ~ 10.44 13.25 29.27 33.32 19.15 23.62 8.63 8.53 9.43 10.76 13.51 14.56 ^ ^ ^ ^ All Children Live in Home (R's with children, n=5708) Have Child/ren Living Outside Home, But All Within Municipality (n=5708) Have Child/ren Living Outside Municipality, But All Within Province (n=5708) Have Child/ren Living Outside Province (n=5708) ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ 0.42 0.21 0.15 0.22 0.49 0.40 0.36 0.41 Number of Respondents in a "Family" (percentage of sample) Household size Resident Family Size Total Family Size (including non-resident members) ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ Note: ^ indicates differs at p < 0.001 from means derived using traditional definition; # indicates differs at p < 0.001 from means derived using expanded residence-based definition. ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^, # 21 Table 2: Percentage of Household Heads in Each Family Structure Arrangement, Netherlands Sample Compared to U.S. Census Statistics* Netherlands 58 57 1 U.S. 50 50 0 Single (including cohabitors) Single (not including cohabitors) 42 31 50 45 Cohabiting Opposite-Sex Cohabiting Same-Sex Cohabiting * U.S. Census 2003, 2004 12 11 1 6 5 1 Married Opposite-Sex Marriage Same-Sex Marriage 21 Table 3: Weighted Percentages of Assistance/Resource-Sharing Variables, for Repsondents with Non-residential Children Aged 15+* PERCENT OF R's WHO HAVE RECEIVED PERCENT OF R's WHO HAVE GIVEN ASSISTANCE/RESOURCES FROM NON-RESIDENT CHILDREN** ASSISTANCE/RESOURCES TO NON-RESIDENT CHILDREN** Housework Other Practical Advice or Financial Housework Other Practical Advice or Financial Help Help Counsel Help/Gifts Help Help Counsel Help/Gifts All w/Non-Res. Kids Aged 15+ (n=2890) 28.2 44.5 67.9 3.0 39.9 56.7 84.5 29.4 BY AGE OF HH HEAD: Heads < 30 yrs. old (n=0) Heads 30-45 yrs. Old (n=89) Heads 46-60 yrs. Old (n=1295) Heads > 60 yrs. Old (n=1506) N/A 45.8 34.0 22.3 N/A 34.3 46.5 43.4 N/A 50.1 68.1 68.6 N/A 3.4 2.0 3.9 N/A 42.4 45.5 34.9 N/A 57.4 67.4 47.5 N/A 90.5 91.9 77.9 N/A 25.2 35.3 24.6 * Note: Information on the sharing of practical, emotional, and financial resources with non-resident children was obtained for up to two randomly chosen non-resident children (either biological or adopted children) who were aged 15 or older at the time of the interview. Thus, these measures do not necessarily reflect overall levels of assistance received from or given to all non-resident children. ** Note: Questions regarding housework help, other practical help and advice/counsel asked about whether these activities occurred or resources were shared during the previous three months. The question regarding financial help/exchange of gifts asked whether any exchange of "substantial " value had occurred within the last 12 months. 22 Figure 1: Mean Resident Family Size (Standard Residence-Based Definition) vs. Total Family Size (Broadest Non-Residence-Based Definition), by Family Structure 5 4.5 4.5 4.1 4.1 4.0 4 3.7 3.6 3.3 Family Size 3.5 3 2.6 2.6 2.5 2.5 2.2 2.1 2.0 2.4 2.2 2 1.5 1 0.5 N/A N/A N/A 0 Full Sample Two Married Two Cohabiting Adults w/o Kids in Adults w/o Kids in Home (n=1913) Home (n=593) One Adult w/o Kids in Home (n=2218) "Single" Adult (Alone or Cohabiting) w/o Kids in Home (n=2811) Resident Family Size Two Married Adults w/Kids in Home (n=2413) Two Cohabiting One Adult w/Kids Adults w/Kids in in Home (n=410) Home (n=329) Total Family Size "Single" Adult Alone or Cohabiting w/Kids in Home (n=739) 23 Figure 2: Mean Resident Family Size (Standard Residence-Based Definition) vs. Total Family Size (Broadest Non-Residence-Based Definition), by Age of Household Head 5 4.4 4.5 4.0 4 3.6 3.5 3.3 3.0 Family Size 3 2.8 2.6 2.7 2.5 2.5 2 1.8 1.5 1 0.5 0 Full Sample <= 30 yrs. (n=1129) 31-45 yrs. (n=2809) Resident Family Size 46-60 yrs. (n=2434) Total Family Size > 60 yrs. (n=1779) 24 Figure 3: Mean Age of Children in Household vs. Mean Age of All Children 35 33.3 29.3 30 Age in Years 25 23.6 19.2 20 15 13.3 10.4 10 5 0 Mean Age of Youngest Mean Age of Youngest Mean Age of Youngest Resident Child Non-Resident Child Child (n=5708) (n=3103) (n=3297) Mean Age of Oldest Resident Child (n=3103) Mean Age of Oldest Non-Resident Child (n=3297) Mean Age of Oldest Child (n=5708)