Protoconsciousness and Freud`s two principles of

advertisement

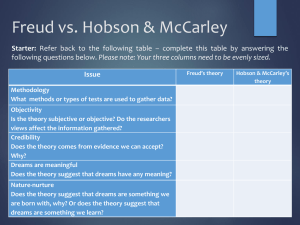

Freud’s ‘primary process’ versus Hobson’s ‘protoconsciousness’ Mark Solms The most influential critic of Freudian dream theory in recent times has been the Harvard Professor of Neurophysiology, Alan Hobson (see for example McCarley & Hobson 1977, Hobson 1988, Hobson 1999). It is a matter of no small interest to psychoanalysts, therefore, that Hobson has just replaced his ‘activation synthesis’ theory (Hobson & McCarley 1977), which he had proposed as an alternative to Freud’s theory, with an entirely new conception. Hobson calls this new conception the ‘protoconsciousness’ theory (Hobson 2009a). The new theory was recently presented to the world in the form of the prestigious William James lectures (Hobson, 2009b). Hobson has now edited these lectures into essay format for the Vienna Circle (Hobson, in press). My comments below are keyed to the essay, which was the last statement of his views that was available to me before the meeting in New York, the proceedings of which form the contents of the present issue. It is clear from the essay — notwithstanding a disclaimer at the outset — that Hobson is still deeply preoccupied with disproving Freudian dream theory. What makes this lifelong preoccupation especially interesting right now is the fact that Hobson’s new model of dreaming closely resembles Freud’s. In this paper I would like to demonstrate how very similar these two (supposedly competing) models now actually are. In doing so, my aim is to clarify the last remaining point of difference between Hobson and Freud. For the avoidance of doubt, I shall quote extensively from Hobson’s essay. Both models start from the observation that the psychological features of dreaming “are so distinctively different from those of waking as to suggest a major reorganisation of underlying brain activity” (Hobson, in press, p.14)1. This major reorganisation is brought about by the state of sleep. This state entails, firstly, according to both Freud and Hobson, a withdrawal of engagement with the 1 My references are to Hobson’s MS which has not yet appeared in print. 1 external world, but more importantly — and here too Hobson’s new theory agrees with Freud’s — it entails deactivation of “the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), the seat of so-called executive ego mechanisms” (Hobson, in press, p.38). This deactivation of the executive “ego” has very significant consequences for the sleeping mind, for the reason that “the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex plays a key role in keeping one on track on whatever state of consciousness prevails “(ibid). Foremost amongst these consequences is a major reduction in “working memory, self-reflective awareness, volition and planning” (Hobson, in press, p.33) — that is, a major reduction in what Freud called ‘secondary process’ cognition. This in turn releases what Freud called the ‘primary process’ from normal inhibitory constraints. While dream consciousness may appear more free (or less constrained) than waking consciousness, it is not at all clear that dreamers ‘decide’ to do anything or exercise even illusional free will in any way …Things just happened to them, spontaneously as it were. They did not have the dream as much as the dream had them! (Hobson, in press, p.41) This is not the only respect in which Hobson’s ‘protoconsciousness’ resembles Freud’s ‘primary process’. Protoconsciousness is also hallucinatory: According to my protoconsciouness hypothesis, in dreaming we positively activate the visual system and see, at the same time that we simultaneously deactivate analytic systems and do not think …The scientific study of dream consciousness shows very clearly that the brain-mind can be internally activated even when it is actively cut off from sensory input or motor output. When this occurs, internally generated signals drive the system in such a way as to make us believe that we are seeing. This insight 2 strongly constrains our ideas not only about dream consciousness but also those ideas that we harbor about waking consciousness. From the subjective evidence of dreaming we can conclude that formed perceptions, the erroneous assumption that we are awake, and a narrative or scenario structure rich in social, motoric, and emotional content are all synthesized by the brain-mind itself. That capabilities for such an experience are given by brain physiology is also made clear, indicating that the brain-mind, working on its own, creates a model of the world of truly amazing similitude to the world itself. This is primary consciousness. (Hobson, in press, pp. 42-3) Let us now review the functional properties of this “built-in consciousness generation system” that Hobson calls “primary consciousness,” which is released from executive “ego” control during sleep. First and foremost, we are told by Hobson that it is a “predictor” which “fills in” the brainmind’s “expectations” (Hobson, in press, p.48). The brain-mind’s intrinsic tendency to activate “its own expectant codes that are generated offline, via the spontaneous activation of neurons by internal signals” (p.42) is normally constrained by realistic cognition; but in sleep “these critical cognitive functions are in abeyance” (p.43). In consequence, the brain’s primary “predictive model [is not] checked against reality” (ibid). This is precisely what Freud claimed: dreaming is characterized above all by the release of reality constraints upon wishful thinking. I am well aware that Hobson will insist that his view of the brain’s spontaneous tendency to generate “predictions” and “expectations” differs from Freud’s view that it generates “wishes,” so let us quickly move on to consider Hobson’s view of the nature and origin of this primal mental tendency. He explains that the “ability to elaborate upon visual stimuli, to fill in, to flesh out, and to imagine the impossible, to create,” which characterizes protoconsciousness and dreaming, is due to the fact that: when dreaming, you are … psychotic … you have hallucinations and delusions. It is 3 faint comfort to regard these processes as non-conscious [in waking cognition], as if that designation helped you escape the obvious: the hardware for psychosis is built into the brain. (Hobson, in press, p.49) It is generally recognized that the “hardware for psychosis” revolves centrally around the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system — the brain’s intrinsic “predictive” and “expectant” system. It is therefore very important to note that Hobson now concedes that dreaming sleep is characterized by enhanced, pulsatile dopamine release. He still tends to minimize dopamine somewhat by mainly emphasizing its motor over its motivational functions, and likewise emphasizing the concomitant acetylcholine enhancement and demodulation of the other monoamine systems, but this does not detract from the fact that he now formally acknowledges the central role of dopamine in dream consciousness: Acetylcholine (ACh) and dopamine [DA] release are not suppressed in REM sleep. If anything, they may be more potent than they are in waking … Dopamine and acetylcholine are both major players in normal motor control. It is thus plausible that the offline running of motor programs, emphasized by the activation synthesis theory of dreaming, is supported by the abundant availability of these two neuromodulators in REM sleep. The pulsatile release of Ach and DA in the thalamus and cortex, and other subcortical motor areas, could be related to the subjective experience of motoric animation in REM sleep dreams. The fact that experimental animals with pontine lesions, and patients with REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) act out their dreams is significant … The net effect, in both cases, is a tendency for motor commands, normally suppressed in REM sleep by active motor inhibition, to be acted out, often awakening the animal or human subject. (Hobson, in press, p.28) 4 Elsewhere in his essay Hobson explicitly acknowledges that the “motor commands” issued during REM sleep are, above all, instinctual motor commands: [Animals in REM sleep with the above-described lesions] jumped to their feet and executed a complex motor sequence of attack and defense postures. An inescapable inference was that during REM sleep dreams such movements are commanded but they are normally prevented from expression by the motor inhibition … The implications for the motoric animation of dreaming are self-evident. Protoconsciousness theory welcomes the functional significance of what would appear to be elaborate behavioral programming of instinctual acts such as escape, defense, and attack. The readout of these behaviors during REM sleep-without-atonia would seem to suggest that the brain is automatically programmed to emit important survival movements. These movements may normally be inhibited but can be experienced by us in dream consciousness …This aspect of the theory fits with other predictive or anticipatory features of our virtual and actual behavioral repertoires. (Hobson, in press, p.26) In short, Hobson now admits that dreaming consists in a primitive type of thinking, characterized by spontaneous “expectations” (of hallucinatory intensity), colored by instinctual action tendencies that are normally suppressed and controlled by the “executive ego”. This might naturally lead to the assumption that dreams reveal primitive motivations. It is therefore not entirely surprising to find that, even in this respect, Hobson appears to be tentatively coming round to the Freudian view: Dream cognition, however bizarre, is usually salient with dream emotion. This salience is robust enough to lead us to consider that dream emotions may shape, or even trigger, 5 dream cognition. Dreaming may be ‘crazy’ in its hallucinations and delusions, its incongruity and its discontinuity, but it does make sense emotionally. This could be good news for the dream interpreters, but a word of caution is indicated. The emotion dream-cognition link may be neither as unique nor as profound as most psychological dream theories suppose. Furthermore dreams may not be uniquely informative about an individual’s associations to emotional stimuli. (Hobson, in press, p. 28) So, although dreams are not unique in this respect, they do in principle admit of interpretation. This is because “the emotional-cognitive system usually, but not always, plays by a strict set of associative rules” (Hobson, in press, p. 14). Hobson elaborates: The unfettered play of dopamine in REM sleep is in keeping with the assumption that dreaming is “motivated” and that important motivational goals may be revealed in dreams. Dreams are not entirely meaningless and there is still room for considering them as uniquely hypermeaningful. This [however] is an unproved hypothesis… (p.29) Ever cautious, Hobson continues: Dynamically repressed (or actively forced down) mental content may well emerge in the process of dream image creation and plot selection processes that activation-synthesis credits with dream production, but such material is neither necessary nor sufficient for dreaming to occur in sleep. Dreaming is neither the only, nor necessarily the most privileged, way of getting at those psychic residues of trauma and conflict that constitute a kind of informational infection of the brain-mind. (p. 46) Notwithstanding the ongoing disclaimers, he concludes: 6 Sometimes dreams do reveal that earlier life issues, long believed dead, are still very hot in our non-conscious brain-minds. Freud does deserve credit for insisting on the long term persistence of conflict and trauma. Unjustified by dream science, however, is any interpretation scheme based upon the central Freudian hypothesis that forbidden infantile wishes cause dreams via the stimulation of disguise-censorship mechanisms. (p. 47) This brings us to the only really substantive point of disagreement that remains between Hobson and Freud: The purpose of this shift [in sleep] from secondary to primary consciousness is not to protect secondary consciousness. On the contrary, it is to restore the sensitivity and specificity of dream consciousness to support waking consciousness. This specific example of brain activation shows how close the psychoanalytic and activation-synthesis models can get to one another; but the mechanisms and functions detailed by the two models are diametrically opposite. We are forced to choose between one or the other. Psychoanalysis views dreaming as unconscious mental activity that is designed to protect consciousness from disruption by the unconscious mind. Activation synthesis regards dreaming as evidence of a built-in consciousness generation system. (Hobson, in press, p.42) In other words, for Hobson, there is no conflict between the sleeping executive ego and the instinctual action tendencies that are released during sleep. To be clear: while Hobson has moved “closer to Freud’s idea of the ego … in my use of this concept I am hoping to explain what the postFreudian psychoanalysts called the ‘conflict-free’ ego” (Hobson, in press, p.42). For this reason, according to Hobson, the anxiety that is so ubiquitous in dreams is simply a manifestation of limbic 7 anxiety-generating mechanisms; it is not a defensive response by the sleeping ego to the disinhibited limbic system. There is therefore no need to postulate the censorship function that (according to Freudian theory) reduces anxiety and thereby prevents the dreamer from waking up. It is inconceivable that the brain-mind states of wake and dream consciousness are not somehow complimentary and reciprocal … It remains to be determined exactly how. We already know enough to make intelligent hypotheses of what this functional reciprocity might be. They include the enhancement and revision of learning and memory, the refreshment and maintenance of temperature control networks and the balance of circuits necessary to assure psychic equilibrium. These surprising functional benefits outweigh and diminish the psychoanalytic idea that dreaming is the guardian of sleep ... Freud’s sleep guardian theory is replaced by the physiological processes that guarantee the preservation of sleep in the face of internal brain activation. (Hobson, in press, p.43) In conclusion, then, although Hobson now accepts “as if we didn’t know it already” (ibid, p.19) that the available evidence proves “beyond the shadow of a doubt that dreaming is as much a psychodynamic as it is an organic [process]” (ibid.), he still finds no evidence for Freud’s hypothesis to the effect that the function (or biological purpose) of the psychodynamics of dreaming is the preservation of sleep. Fortunately, this last remaining point of disagreement — stripped of all the ideology — can be resolved empirically. I would like to propose a critical experiment to decide the issue once and for all. If Freud’s sleep-protection hypothesis is correct, then patients who lose the capacity to dream (in consequence of posterior cortical lesions) should suffer from poor quality sleep, with frequent microarousals, arousals and awakenings. If this is not found to be the case, then Freud’s sleep protection theory will have been refuted. I accept responsibility for undertaking this critical experiment, and 8 declare that I shall accept a negative result as definitive falsification of Freud’s hypothesis. I hope that Hobson — as a truth-loving scientist — will likewise accept the corollary implications of a positive result. 9 REFERENCES Hobson, J. A. (1988). The Dreaming Brain. New York: Basic Books. Hobson, J.A. (1999). The New Neuropsychology of Sleep: Implications for Psychoanalysis. Neuropsychoanalysis, 1,157-183. Hobson, J.A. (2009a). REM sleep and dreaming: towards a theory of protoconsciousness. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 10, 803-81. Hobson, J.A. (2009b). Dream Consciousness. Presented as the William James Lectures at Roehampton University. Hobson, J.A. (in press). Dream Consciousness. In O. Flanagan (ed). Vienna Circle Book Series. Springer Verlag. Hobson, J.A. & McCarley, R. (1977) The brain as a dream-state generator: An activation-synthesis hypothesis of the dream process. American Journal of Psychiatry, 134, 1335-1368. McCarley, R. & Hobson, J. A. (1977). The neurobiological origins of psychoanalytic dream theory. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 134, 1211-1221. 10