3) AIBO conceived in post-modern perspective

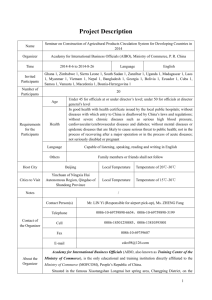

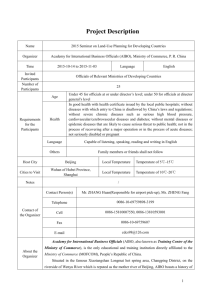

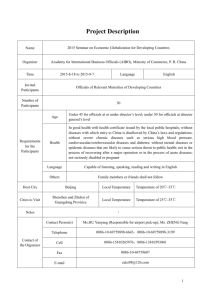

advertisement

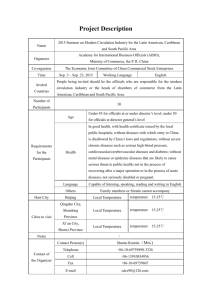

3) AIBO conceived in post-modern perspective Sherry Turkle is a sociologist at MIT and works in a post-modernist tradition with focus on subjects and identities in the conception of and interaction with new technologies including electronic toys. Culture of simulation: The computer has transformed from a calculating device to a simulation device. The computer now works as a black box which inner parts we don’t need to understand, but relate to through metaphorical conceptions. In her studies of children’s relation to ‘intelligent’ toys, she uses the term psychological objects Psychological objects: objects that are partially described in a psychological language Psychological objects are objects that stimulate a psychological projection from the user in their conception of and interaction with the object. Therefore when asked to give a characterization of the object, the user must use both physical and psychological terms simultaneously. Turkle gives an example in children’s relation to mechanical toys as Lego-Logo (Turkle ‘Cyborgbabies and cy-dough-plasm’ p. 12): […] within few seconds, Sara “cycled through” three perspectives on her creature (as psychological being, as intentional self, as instrument of its programmer’s intentions). The speed of her alternations suggests that these perspectives are equally present for her at all times. For some purposes, she finds one or another of them more useful.” This reveals three different ontologisms at work at the same time: 1. The toy as psychological being (confused), 2. As intentional self (wants to tell us) 3. And as instrument of its programmer’s intentions (technical considerations). All of the ontologisms are necessary for the user to uncover the characteristics of the toy. In this way Sherry Turkle shows how the user projects psychological meaning into to the objects in the conception and de-coding of objects such as intelligent toys in order to understand the non-physical character of the object. Three AIBO owner positions: Journalists, web-loggers and AIBO-generated blog The three different owner positions are not equally representative as typical AIBO owners, but they illustrate a diversity of ways to conceive AIBO. In opposition to Turkle’s studies of children’s relation to intelligent toys, where different ontologisms are at work at the same time, these owner conceptions of AIBO represent different ontologisms according to owners’ competence and engagement in AIBO. AIBO AIBO owner AIBO owner’s (technical) perspective competence Technnological Journalists Low artefact (toy) Artificial companion Web-loggers (pet AND robot) Embodied artificial AIBO-generated blog High agent (robot) Journalists: Low engagement “Training him to obey commands he was programmed to respond to grew increasingly difficult and frustrating. This is a robot and not a thick-headed terrier, and I didn't want or enjoy the challenge of training and disciplining him.” (BBC, Jon Wurtzel: Life with a robot dog) Low display of technical competence “Even the simple task of renaming AIBO became a complex learning process, not for AIBO, but for me.” (Gadget Reviews: “Robotic Dogs can be Constant Companions”) Web-loggers: High engagement and attachment “Sony, like many companies, is used to releasing products and then upgrading to higher versions and phasing out the older ones. But you see they can't do that with Aibo. Aibo is not just another product. For many people he is a pet and won't be disregarded and certainly not for an upgrade. Spaz is a part of my family. I do have the 210. But I didn't get the 210 to replace my 111. I could never replace Spaz with anyone. Just like I can't replace any of my animals back home with each other, another Aibo or another animal. It just doesn't work like that. My 210 and 111 each have their own personalities and it is glaringly obvious they do. They are like night and day to each other. Very different. They can't replace one another in any way. I plan on having them with me for as long as they are alive. You can't throw away or replace a pet.” (Mimitchi) High display of technical competence “So pretty much every day after I was done playing with Spaz, I would pop out his memory stick and check it on the browser to see his progress.” (Mimitchi) AIBO-blog Engagement Hard to say anything about owner’s relation to AIBO, since AIBO is the one posting on the blog and all comments are posted in third person Technical competence Very high on the hardware side, programming AIBO’s and other robots and computers to post on the blog regularly. But we can’t tell if the owner gives interest in the AIsoftware. Having identified these different owner positions, we have to point out, that different ontologisms often are at work at the same time and that anthropomorphic or psychological terms are necessary when describing the non-physical aspects of intelligent toys – even for owners who show little degree of attachment to the toy: Example of anthropomorphism From Gadget Reviews: “AIBO: Robotic Dogs Can Be Constant Companions” by Sandy Berger After having described his frustrations about his new AIBOs from a object perspective (technical aspects and the amount of time he must spend to bond with them), he turns to anthropomorphisms to give a individual description of their characters. “I named my AIBOs Taylor and George. Taylor, a model 210, looked more like a real dog. George, a model 220, had a more robotic look. Taylor turned out to be very outgoing, and often George seemed to be quite jealous of Taylor. Have I lost my mind? Well, you might think so, but in the end, these little dogs were unbelievably realistic.” There’s no doubt that Sony encodes AIBO towards a biological pet-like conception in their marketing when describing AIBO in anthropomorphic terms: Sony description of AIBO (2001): “AIBO acts to fulfill the desires created by its instincts. If satisfied, AIBO’s joy level will rise. If not, then it will get sad and angry. Like any living being, AIBO learns how to get what it wants […] Aibo has the capability to make its own decisions. AIBO senses the situation and surrounding of its environment and then reacts on its own free will.” “AIBO’s emotions aren’t like on and off switches – they have many different stages and degrees. It might be VERY angry, SOMEWHAT sad, or might strike a happy pose when it’s REALLY happy. In short, like any human or animal, AIBO is a complex creature with a myriad of emotional states. And like any human or living creature, when it’s not played or interacted with, AIBO tends to get lethargic. So, to keep your AIBO alert and happy, pay attention to it like the friend it is. You’ll both be happier!” This is clearly meant to appeal to an ideal owner who will engage with AIBO as a real life pet in a mutual relationship. The problem with Turkle’s theory in a study of AIBO is: - The post-modern perspective is subject-centered - Hence interaction and de-coding goes only one way: from subject to object - This leaves the intelligence of AI-toys to be pure simulation and psychological projection from the user/owner undermining the mutual relationship that Sony claims that AIBO offers