The scarcity of organs available for transplantation carries many

advertisement

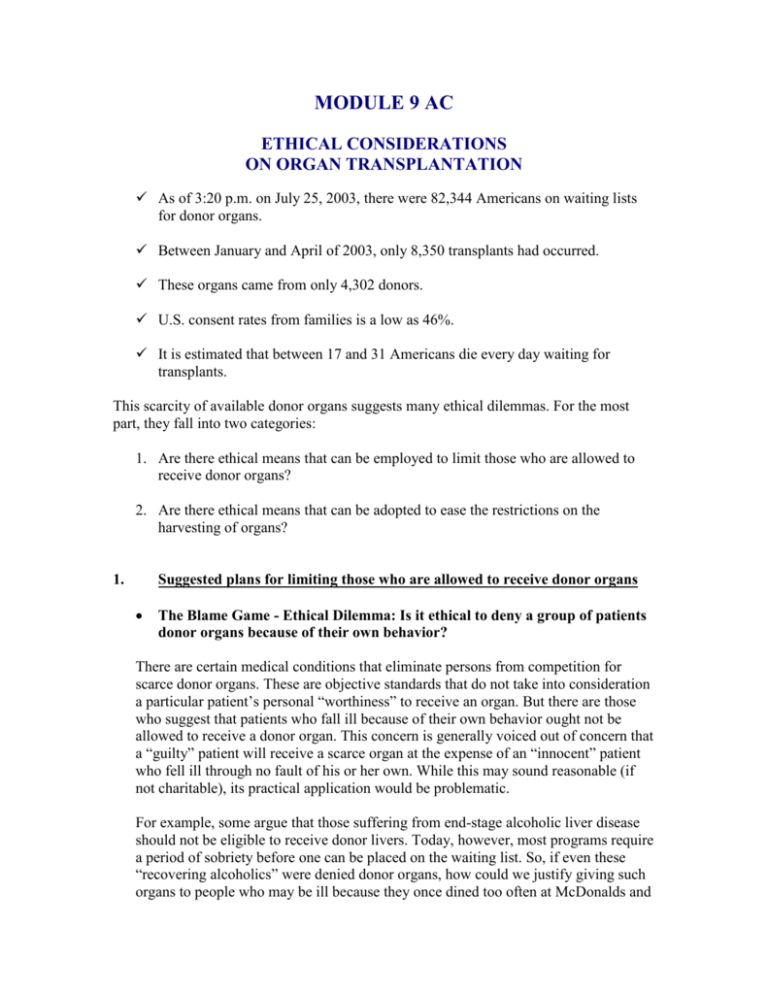

MODULE 9 AC ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS ON ORGAN TRANSPLANTATION As of 3:20 p.m. on July 25, 2003, there were 82,344 Americans on waiting lists for donor organs. Between January and April of 2003, only 8,350 transplants had occurred. These organs came from only 4,302 donors. U.S. consent rates from families is a low as 46%. It is estimated that between 17 and 31 Americans die every day waiting for transplants. This scarcity of available donor organs suggests many ethical dilemmas. For the most part, they fall into two categories: 1. Are there ethical means that can be employed to limit those who are allowed to receive donor organs? 2. Are there ethical means that can be adopted to ease the restrictions on the harvesting of organs? 1. Suggested plans for limiting those who are allowed to receive donor organs The Blame Game - Ethical Dilemma: Is it ethical to deny a group of patients donor organs because of their own behavior? There are certain medical conditions that eliminate persons from competition for scarce donor organs. These are objective standards that do not take into consideration a particular patient’s personal “worthiness” to receive an organ. But there are those who suggest that patients who fall ill because of their own behavior ought not be allowed to receive a donor organ. This concern is generally voiced out of concern that a “guilty” patient will receive a scarce organ at the expense of an “innocent” patient who fell ill through no fault of his or her own. While this may sound reasonable (if not charitable), its practical application would be problematic. For example, some argue that those suffering from end-stage alcoholic liver disease should not be eligible to receive donor livers. Today, however, most programs require a period of sobriety before one can be placed on the waiting list. So, if even these “recovering alcoholics” were denied donor organs, how could we justify giving such organs to people who may be ill because they once dined too often at McDonalds and KFC; used illegal drugs; had unsafe sex; or smoked? How could we even ascertain these facts? As an aside, the argument that alcoholics might start drinking again— and will thus “waste” the new livers—does not hold up to scientific scrutiny. Survival and retransplantation rates are the same for drinkers as for those who abstain.1 Further, could we be sure that overeating, unsafe sex, and drug abuse would not begin anew? Another problem: Alcoholism is now understood to have some genetic element, and scientists have discovered a “risk-taking” gene as well. If a recovering alcoholic is vying with a daredevil for a particular donor liver, can a credible ethical argument be made that the alcoholic is somehow more responsible for needing the new liver than the cliff-diving daredevil? Or is the alcoholic more “guilty” than a person who destroyed her liver sniffing glue? And what of the person who was simply too careless to read the bottle of Tylenol, and washed the acetaminophen down with scotch? The standard practice today is to avoid impossible value judgments and to grant places on the waiting lists on the basis of medical criteria alone. For alcoholics, obtaining a place may require a period of sobriety, just as weight loss, diet, and similar health habits may first need to be addressed by others. Other considerations on limiting recipients include asking whether priority should favor the sickest patients or those with the best chance of survival; time on the waiting list or need. Reciprocity – Ethical dilemma: Is it ethical to distribute donor organs on a quid pro quo basis? Some suggest that only persons who voluntarily sign up to be organ donors while healthy could receive a donor organ if the need arose. Signing up could not be done retroactively. This approach would require considerable ongoing education of the population. It is problematic in that young people often fail to acknowledge that they may someday fall ill or be injured, and many might thus fail to sign up to be donors. 2. Suggested plans for easing the restrictions on harvesting organs– Ethical Dilemma: Ethical Dilemmas: What degree of consent must be sought before harvesting dead donor organs? How do we best address the need for freely given consent from living donors? Rather than eliminating potential recipients from waiting lists, perhaps the critical shortage of transplantable organs is better addressed by easing the restrictions on See, for example, Paul Cotton, “Alcohol’s Threat to Liver Transplant Recipients May be Overstated, Suggests Retrospective Study,” Journal of the American Medical Association 27 (23) (June 15, 1994): 1815-17. 1 obtaining those organs from both dead and living donors. Suggestions for doing so include some that are ethical and some that are problematic at best. Dead Donors: At present, the final permission to take organs from a person who has died comes from that person’s survivors. Even if the person has indicated that he or she wants to be a donor, organ procurement organizations (OPOs), hospitals, and physicians are virtually always unwilling to harvest organs if survivors object. It is generally felt that out of respect for those who are mourning, for the good of hospital/community relations, and to avoid scandalous stories that might impede organ donations, it is better to pass than to harvest the organs when family members object. Increases in organs for transplantation have been achieved through both organ sharing (in which a liver might be split, with two patients each receiving one lobe), or through a procedure known as “domino transplantation.” An example of a domino transplant occurred recently when surgeons transplanted the intestines of a dead donor into a young. Her functioning liver was removed because, "By putting the entire package from the donor in, we have to make much less connection, and the concern about size discrepancy is not a significant issue," her surgeon explained. He then transplanted her liver into another patient. Other ideas for maximizing dead donor organ donation include: Widespread activist education about the realities of organ donation - The involvement of schools and churches is encouraged. (Many people erroneously believe that their religion does not allow organ removal.) Universal donation – this approach would allow OPOs to harvest organs from every eligible dead person unless given specific instructions to the contrary from the individual or his or her family. Compulsory removal - based on the power of the state to prevent wasting of valuable assets by the deceased, organs would be taken without seeking the permission of survivors, and regardless of any objection. Mandated Choice – everyone would be asked, upon turning 18, whether or not he or she wanted to be an organ donor. Family members could not overrule this decision after the person’s death. Payment for organs – suggestions range from covering the funeral coasts of the donor to substantial set payments or free-market private purchase arrangements. Executed persons – suggestions range from allowing prisoners who are going to be executed to donate organs, to simply taking organs from all medically eligible executed prisoners. Taking organs from patients in a persistent vegetative state, who would then continue living as before (using a “greater need” argument), or after the decision to end life support has been made. Living Donors: Great scientific inroads have been made over the last decade in this regard. Living donors are able to donate “spare organs,” such as one kidney, or one lobe of a liver. At present, this must be a “not-for-profit” act of generosity, usually among family members, but occasionally from an altruistic non-related donor. Ethical problems do exist, and must be dealt with with great discretion. For example, a circumstance can arise in which a family may know that one member is a possible match and a potential organ donor, capable of saving the life of another family member. The potential donor may feel great pressure to do so, even if he or she does not want to. This issue is generally handled through a private interview with medical staff. If it is clear that he or she does not want to donate, family will be told that the complete set of test results shows that the person would not, after all, be a match, and thus cannot donate. Other ethical questions surround parental permission for a minor to be a donor. Does a parent have a right to remove a healthy organ from a healthy child, even to save the life of another? Other ideas for maximizing living donor organ donation include: Payment for organs – This would allow individuals to sell the above mentioned “spare organs” to the highest bidder. Some even support permitting U.S. patients to purchase organs from Third World donors. Prisoner donation – Some suggest allowing parole for prisoners who donate organs Other Possibilities: Rebuilt organs – see http://organtx.org/ethics/marginal_donors.htmm Genetically built organs Cloned organs Xenotransplantation – see, http://akak.essortment.com/whatisxenotr_rgsy.htm