Please, feel in you abstract title here

advertisement

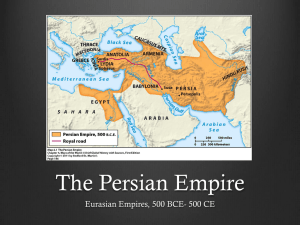

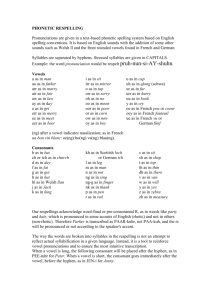

The multi-faceted vowel change: A diachronic perspective on Old, Middle, and Dari Persian Alireza Dehbozorgi PhD candidate in general linguistics, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran Iran (email: alirdehboz@hotmail.com) It is well known that vowels change within the passage time. Several linguists have published impressive ideas about this phenomenon. For instance, Labov (1994: 116) claims that chain shifts are restricted by the following four principles1: I. In chain shifts, long vowels rise II. In chain shifts, short vowels fall III. In chain shifts, the nuclei of upgliding diphthongs fall IV. In chain shifts, back vowels move to the front These principles have been inferred based on a cross-linguistic investigation. Principle I has been observed in 15 languages (i.e. English, German, Yiddish, Swedish, Frisian, Portuguese, Swiss French, Romansch, Greek, Lithuanian, Old Prussian, Albanian, Lappish, Syriac, and Alcha). Principle II has been observed only in two languages (i.e. North Frisian, Vegliote). Principle III (IIa in Labov’s work) has been observed in 10 languages (i.e. English, Yiddish (Central), Yiddish (Western), Swedish, North Frisian, Romansch, Vegliote, Czech, Lettish, and Korean). And finally, principle IV (III in Labov’s work) has been claimed to hold for 9 languages (i.e. Yiddish, Swedish, North Frisian, Romansch, French, Lettish, Greek, Albanian, and Alcha). On the whole, 23 languages and varieties have been put investigated in a comparative fashion in this work. Elswehere in the same book, he claims that “[A] vowel can move front and down at the same time, or front and up, but it cannot move both up and down, and the principles do not mention movements to the back.” (ibid. 121) Unfortunately languages from the Indo-Iranian (Indo-Aryan) have simply been neglected from this invaluable comparative study. Ringe and Espa (2013) also review the approaches to sound change of which Labovian one seems to be considered the most important throughout this book. Throughout its historical development, Persian has undergone various vowel changes many of which seem to be in conflict with Labov’s principles of vowel shift. For instance, front vowels have been backed as we see in the change of the words wināh and wišād in Turfani and Zoroastrian Middle Persian which have changed into gohāh and gošād in Dari Persian, respectively (Abolghassemi 2010: 24-25). There are several more of these counterexamples as found in Persian historical Grammars (see e.g. Abolghassemi 2010 and Kent 1953, among others). The present research paper will present the counterexamples to some of the most dominant sound change principles, especially Labov’s, based on a thorough investigation of Old, Middle, and Dari Persian. The results of this diachronic comparison seems to suggest that much more counter examples of this (almost 150). These cannot also be accounted for in terms of lexical diffusion theory. This corpus-based research uses the most comprehensive corpora of these varieties of 1 . In the original text, II and III are II and IIA ,respectively. Persian such as Titus corpus of Frankfurt University for Old and Middle Persian, Parsig corpus for Middle Persian and several quite recent books on historical grammar of Persian such as Kent (1953) on Old Persian, MacKenzie (1971) and Nyberg (1974) on Middle Persian, and finally Abolghassemi (2010) which is an almost complete historical grammar of Persian covering all the linguistic stages from Old Persian to contemporary spoken Persian. When reference is given to several other languages and other varieties, sufficient use has been made of Beekes (2011), Comrie (2009), and Ringe and Espa (2013). When necessary, data from other Iranian languages are also used to verify the existing evidence using mainly the field data and books such as Windfuhr (2009). Throughout this study, every type of vowel changing including root and suffix vowel gradation (ablaut) is taken into consideration. The results of this comparative-diachronic study demonstrate that, contrary to Labov’s claims, front vowels move back (e.g. i > o) in the history of Persian languages. The same holds for the falling of long vowels (e.g. ī > a), the raising of short vowels (e.g. o > u). Consequently, one has to reconsider the role of regularity in vowel change with insight especially from the Iranian branch of the Indo-Aryan language family. The results will certainly open new windows to sound change and here especially vowel changes. In other words, they can deepen our understanding of the nature of this phenomenon to a considerable extent by proposing a new theoretical approach which can be used for both synchronic and diachronic as well as comparative studies of both kinds. This approach which may be called multi-faceted vowel change puts emphasis more on how the seemingly irregular vowel changes can be described and explained by various new principles. To put it into a nutshell, both the descriptive and theoretical results of this study will profoundly change our current view on the nature sound change. keywords: vowel change, regularity, Labovian Paradiagm References Abolghassemi, M. (2010). A historical grammar of the Persian language. Tehran: SAMT. Beekes, R. S. P. (2011). Comparative Indo-European linguistics: An introduction. (2nd Ed.). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Comrie, B (ed.) (2009). The Iranian Languages. (2nd Ed.). New York: Routledge. Kent, R. G. (1953). Old Persian: Grammar, texts, and lexicon. New Haven: American Oriental Society. Labov, W. (1994). Principles of linguistic change, vol.1: Internal factors. New York: WileyBlackwell. MacKenzie, D. N. (1971). A concise Pahlavi dictionary. London: Curzon Press. Nyberg, H. S. (1974). A manual of Pahlavi. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrossowitz. Ringe, D. and J. F. Eska, (2013). Historical linguistics: Toward a twenty-first century reintegration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. The TITUS corpus of Old and Middle Persian: titus.uni-frankfurt.de Windfuhr, G. (2009). The Iranian languages. Oxford and New York: Routledge.