Quintos, MR, Isleta PF., Chiong CC., Abes GT. 2003. Newborn

advertisement

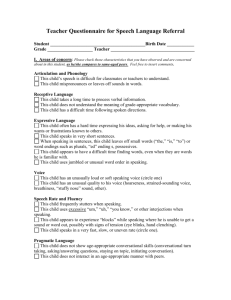

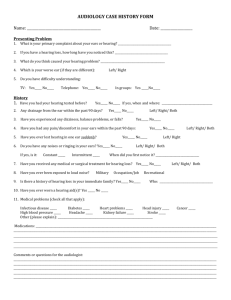

A Survey of the Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Pediatricians in relation to Newborn Hearing Screening A Research Proposal Presented to The Department of Preventive Medicine University of the East Ramon Magsaysay Memorial Medical Center Aurora Blvd., Quezon City In Partial Fulfilment Of the Requirements for the Degree in Doctor of Medicine By Alonzo, Cyndi B. Aldaba, Christine Victoria C. Almenario, Mark Jester A. Bato, Charmagne Ross E. Batoon, Cecille Marie Julienne G. Bautista, Leila Marie R. Benito, Jelyn Rose F. Boncoc, Paul Reginald M. Borela, Jopet Esther L Buenaventura, Lee Roi F. Buenaventura, Nicolo F. ABSTRACT OBJECTIVE. Universal newborn hearing screening focuses on providing the earliest possible diagnosis for infants with permanent hearing loss. The goal is to prevent or minimize the consequences of sensorineural hearing loss on speech and language development through timely and effective diagnosis and interventions, thereby improving their academic and vocational achievements. Pediatricians are in a key position to educate families about the importance of follow-up care and ensure appropriate surveillance, if they are well informed. The objective of this study was to survey the attitudes, practices, and knowledge of pediatric consultants in relation to newborn hearing screening. METHODS. A survey was created on the basis of input from focus groups with primary care physicians. Surveys (n=126) were distributed to all pediatric consultants affiliated to 17 training hospitals in Quezon City regarding their practices, knowledge, and attitudes related to universal newborn hearing screening. The response rate was 47.62% (n=60). RESULTS. Physicians reported a high level of support for universal newborn hearing screening; 90% of the clinicians deemed it very important to screen all newborns for hearing loss at birth, while the remaining 10% viewed it as somewhat important. Although pediatricians reported confidence in talking with parents about screening results, they indicated a need for further training in order to counsel parents better after making a diagnosis. Several important discrepancies in the knowledge of the pediatricians about the seriousness and consequences of hearing loss were identified, and these represent priorities for education, as based on their relevance to medical management and parent support. CONCLUSION. Pediatricians support the efforts of Newborn Hearing Screening and its procedure. However, a more in-depth awareness about Newborn Hearing Screening among pediatricians is highly recommended to bridge the knowledge gaps through primary sources of information and provision of action-oriented resources that aid in the familiarity not only about Newborn Hearing Screening but also hearing loss itself in order to put the pediatricians in a better position to support families on identification of infants with hearing loss and prevention of its consequences. Keywords: newborn hearing screening, physician knowledge, childhood hearing loss, sensorineural hearing loss Abbreviations: NBHS- Newborn Hearing Screening SNHL—sensorineural hearing loss EOAE – evoked otoacoustic emissions AAP—American Academy of Pediatrics Introduction Hearing loss affects approximately 2-4 per 1000 live births infants and has been estimated to be one of the most common congenital anomalies leading to impediment of speech, language and development if undetected. Its prevalence has been shown to be greater than that of most other diseases and syndromes (eg, phenylketonuria, sickle cell disease) screened at birth. Furthermore, the occurrence of hearing loss has been estimated to be more than twice that of other screenable newborn disorders combined. Universal newborn hearing screening has become the standard of care throughout the United States in an effort to provide early detection and intervention for infants with permanent hearing loss. In 1993, <5% of newborns were screened for hearing loss. Today, 93% of newborns are screened for hearing loss before hospital discharge, and 39 states in the United States have universal newborn hearing screening legislation. (Erenberg et al., 1999) The expansion of newborn hearing screening in the past decade has helped reduce the average age of identification of infants with permanent childhood hearing loss, allowing families and professionals to prevent or minimize the negative impact of sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) on speech and language learning (Vohr et al., 1998). The overall success of these efforts, however, depends on the provision of timely and effective diagnostic and intervention services. The Newborn screening program was first introduced to the Philippines in 1996 which was developed by a group of 24 pediatricians and obstetricians from around the metropolitan area, which aimed to establish the incidence of metabolic conditions and to make recommendations for the adoption of newborn screening nationwide. Currently, the Newborn Screening Program in the Philippines includes routine screening for congenital hypothyroidism, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, galactosemia, phenylyketonuria and glucose-6phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (R.A. 9288) and is available in practicing health institutions which include hospitals, lying in clinics and health centers. A study conducted by Olusanya et. Al investigated the initiation and progress of early detection of infants with hearing loss in developing countries. The study showed that in the East Asia Pacific Region, the Philippines had no government support for infant hearing screening, and that it was the only country in the region which had no support program for cases of found hearing loss. In a study done in 2003 in the Philippine General Hospital, neonates were screened for hearing loss using the evoked otoacoustic emissions ( EOAE), which is a universally well known and accepted procedure. During a period of one year, from March 2000 to March 2001, 301 high-risk neonates and 105 non high-risk neonates were identified to be at risk(Quintos, et al. 2003). Although there are disorders screened in the Newborn Screening Program implemented by the government, the screening for the hearing loss of infants should also be included in the program. Thus, it is the aim of this study to determine the knowledge, attitude and practices amongst pediatricians from training hospitals located in Quezon City in relation to the Newborn hearing screening. This has been done by utilizing a questionnaire determining the proportion of pediatricians well informed about NBHS, those with a positive attitude towards NBHS, and those who routinely subject their newborn patients to NBHS, either through referrals or direct implementation. Universal newborn hearing screening focuses on providing the earliest possible diagnosis for infants with permanent hearing loss. The main goal of early identification and intervention programs is to improve the speech and language development of infants and children who are deaf or hard of hearing, thereby improving their academic and vocational achievements. Although the need for successful universal newborn hearing screening programs cannot be denied, the legislative support, technology, and expertise needed to implement such programs on a national level has only recently been realized. Physicians are in a key position to educate families after hearing screening and to ensure appropriate follow-up care and surveillance, particularly for those infants who fail the newborn hearing screening. Newborns and parents are seen regularly by their primary care physicians, and parents often seek input from their physician on the infant’s medical and developmental needs. This provides an ideal opportunity to promote follow-up, make appropriate referrals, and support families. However, this requires that physicians be knowledgeable about the implications of hearing screening results as well as current best practices in the medical and educational treatment of infants with permanent hearing loss. This study will reflect the degree of knowledge of our pediatricians today regarding NBHS, provide leverage on what they still need to know and how they prefer to learn this new information to further improve their practice. Such findings is essential for creating effective partnerships with the medical home to meet the needs of families of infants with newly diagnosed permanent hearing loss. The survey was limited to a total of 60 pediatrician respondents, although we sampled and recruited 126 number of participants from 9 training hospitals overall return rate was 47.62% (n=60). Data analysis was limited to the descriptive assessment of the knowledge, attitudes and practices of pediatricians. The hospitals to which pediatricians are surveyed, were from training hospitals located in Quezon City. This study did not attempt to compare pediatricians coming from private and government training hospital. Future studies may cover on this, as well as to cover more samples involving other hospitals of Quezon City. Methodology Study design and sample size The research made use of a descriptive study design which aims to describe the current status of pediatricians’ knowledge, attitudes and practices with regards to Newborn Hearing Screening by having them answer survey questionnaires. Subjects were acquired from the training hospitals in Quezon City. Training hospitals were chosen because they are the institutions who will produce the next generation of pediatric consultants, thus, it would be best to assess their pediatricians with regards to their knowledge, attitude and practices in relation to the aspect of Newborn Hearing Screening. The minimum sample size for this study to be relevant was 96. Description of population There are a total of 17 training hospitals in Quezon City (Appendix C). From the 17 hospitals, 9 hospitals were willing to participate in the study. These include National Children’s Hospital, United Doctor’s Medical Hospital, St. Luke’s Medical Center, De Los Santos Medical Center, Capitol Medical Center, Dr. Fe del Mundo Medical Center, UERMMMC I, World Citi Medical Center and Philippine Children’s Medical Center. The survey questionnaires were given to all the available pediatric consultants listed to be practicing in the participating training hospitals in Quezon City as provided by the Medical Directors, with no further exclusion and inclusion criteria such as their sub specialization or number of years in practice. As long as the pediatric consultant is affiliated with the selected hospital, he/she was deemed eligible to participate in the study. Description of the survey tool The survey tool, which is the questionnaire, was a modified survey form from the study by Moeller, et al. of the American Academy of Pediatrics who conducted a study to gather the knowledge, attitude and practices of primary care physicians in relation to NBHS in Puerto Rico in 2006. Their questionnaire, which was composed of 22 questions, was reduced to 19. Question 18 (How helpful would the following types of materials be to you in your practice?) and 19 (How frequent do you use the internet to access information about medical topics?) of the original questionnaire were removed because of their similarity to question 15, which asks about the respondent’s primary source of information about newborn hearing screening. Question 20 (Please list any professional medical organizations that have published policy statements about newborn hearing screening) was also taken out because NBHS has not been mandated by the government or any professional medical organization in the Philippines. After the modifications, the survey was pre-tested for length and clarity among 6 pediatric residents in UERMMMC I. After completion, they were asked for comments regarding the questionnaire’s structure and contents. Comments regarding the length of the survey form, which at that time consisted of three pages, were made. Data collection for the pre-test was done approximately 20 minutes after distribution. In response to pre-testing, the number of spaces between questions and the font sizes were reduced in order to make it appear shorter. The survey form was thus reduced to a two- page, one paper form. The estimated time to fill up the questionnaire, which was 15 minutes, was also noted on the first part of the survey form so as to give the respondents an idea on how much time it will take to fill up the survey form. Data Distribution and Collection In each hospital, a letter of consent addressed to the Medical Director was given before handing out the survey forms to every available pediatrician affiliated to their institution. A total of 126 questionnaires were distributed, surpassing the minimum sample size. A copy of the approved letter from the Medical Director was attached to each questionnaire distributed to the pediatricians of each hospital. For consultants who weren’t available to answer the survey at the time of distribution, survey forms were left with their secretary and their contact numbers were noted. They were followed-up every once in a while as to when the survey forms can be collected. The number of collected questionnaires was recorded for each hospital. Statistical Analysis The responses of the pediatricians for each question were tabulated and expressed in proportional percentages. Data and Results Demographics Of the 126 questionnaires distributed to all pediatricians, 60 (47.62%) surveys were returned; these responses form the basis for analysis. Demographic results are shown in Table 1. The samples were well distributed by gender, years of practice and year of birth. On average, respondents reported that 68.48% of their practice was composed of children less than 5 years of age. The same respondents were asked to approximate the number of children with hearing loss that they had seen in the past 3 years. 58.33% reported seeing an average of 6.62 children with hearing loss while 23.33% (n=13) had no known patients with hearing loss. The remaining 18.33% had no answer. Of those who have seen a patient with a hearing loss, the respondents’ average years of practice was 9.48 years while those who did not receive patients with hearing loss had an average of 13.14 years of practice. Attitudes about Newborn Hearing Screening Newborn Hearing Screening has raised concerns about its cost, the impact on parental anxiety and accuracy of such program. This section reports the current attitudes of pediatricians about Newborn Hearing Screening. When the pediatricians were asked about the importance of newborn hearing screening, 90% of the clinicians deemed it very important, while the remaining 10% viewed it as somewhat important (Figure 1, see appendix). When they were asked whether NBHS causes anxiety to the parents, 57% states that it does not while 40% say that this is so. The remaining 3% were unsure. The respondents were also asked about their confidence in explaining the newborn hearing screening process to parents who have questions about the infant’s results. 58% of the respondents were very confident while 35% are somewhat confident. The remaining 7% said they are not confident. Current Practices Related to Newborn Hearing Screening The respondents were asked to whom they routinely refer a child with confirmed permanent hearing loss (Figure 2, see appendix). Notably, 92% of respondents answered that they would refer the family to an otolaryngologist, and 8% said that they would refer to both otolaryngologist and neurologist. Furthermore, none responded that they will refer to geneticist. The Joint Committee on Infant Hearing Screening for children with congenital hearing loss (Moeller, et al., 2006) recommends referals to geneticists for genetic evaluation which could have avoided unecessary and costly clinical tests, allowing one to anticipate potential health problems and therapeutic options. When they were asked for how many Newborn Hearing Screening results they receive for the past year, 62% indicated that they receive <50%. While 27%, receive > 50%, and 12% have no answer. Percieved Knowledge Needs Newborn Hearing Screening has not been implemented in all hospitals by the government. When the pediatricians were asked whether their hospital have an Early Hearing Detection and Intervention Program, 59% (35/60) of the respondents replied that their hospitals do practice the program, while 23% (14/60) replied that their hospital do not have such program, 10% (6/60) were unsure, and the remaining 8% (5/60) had no answer. Of the 59% (35/60) who said that their hospital has a newborn hearing screening program, 63% (22/35) does not really have NBHS in their hospital, while 37% (13/35) of the respondents do have NBHS in their hospital. Of those who answered that their hospital has no newborn hearing screening program, 64% (9/14) has an NBHS program in their hospital, while the remaining 36% (5/14) does not. In summary, only 30% (18/60) correctly answered the question whether or not their hospital has a newborn hearing screening program. 52% (31/60) answered the question incorrectly, and the remaining 18% (11/60) either did not answer the question or was unsure about it. The information of whether or not the hospital has a newborn hearing screening program was confirmed through the Department of Health Advisory Committee on Newborn Screening of 2009. Our Pediatricians do not frequently encounter children with congenital hearing loss in their practice. However, they have expressed strong interest in guidelines and information that would provide to be helpful to the families of this children (Moeller, et al., 2006). As such when they are asked whether their training in medical school meets the needs of infants with permanent hearing loss (Figure 3, see appendix), 28% of the respondents consider their training as adequate. On the other hand 55% judge their training as inadequate regarding this matter while 14% were unsure and 3% had no response. The pediatricians were asked to cite their primary source of information with regards to NBHS. Majority of their sources are from educational meetings like lectures, seminars, and conventions. (Figure 4.) The Department of Health (DOH) has set a maximum rate of P550 for the newborn hearing screening. Aproximate cost of Newborn Hearing Screening in Philippine hospitals like in St. Luke’s Medical Center is P400.00. When the respondents were asked regarding how much will it cost for a NBHS, 37% of the pediatricians responded with an estimated cost beyond P550 while 43% (26/60) estimated the cost to be below P550.00, and the remaining 20% did not have an answer. With regards to the cost of the Newborn Hearing Screening, 88% of the pediatricians claim that NBHS is worth its cost, while 5% says that it is not. On the other hand, the remaining 7% are unsure. Of the 43% (26/60) who had a correct estimate of the NBHS screening, 76.92% (20/26) said that it was worth it, 11.53% (3/26) said they were unsure about it while another 11.53% (3/26) said it was not worth it. In testing the knowledge of these pediatricians, specific questions were asked regarding specific ages when tests, follow-ups and interventions should be done. Table 2 summarizes the responses of the pediatricians regarding these questions and the entries marked with “ * ”indicates the percentage of responses consistent with the guidelines. The Guidelines for Pediatric Medical Home Providers (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2002). The 1-3-6 Guidelines recommends, (1) completed newborn hearing screening before 1 month of age, (2) diagnosis of hearing loss and hearing aid fitting before 3 months, and (3) enrollment in early intervention before 6 months. 32% were able to respond correctly that those newborn who did not pass the hearing screening should recieve additional testing at ≤ 1 month age, 50% of the respondents answered > 1 month, 3% said as soon as possible, 2% at < 1 year of age, and the remaining 13 % were unknown. Regarding the question on the definite diagnosis of newborn hearing loss, 22 % had the correct response that the diagnosis should be done before 3 months, while 62 % answered > 3 months, 1% said before 1 year old, 3% said as soon as possible, and 12 % were unknown. The earliest age at which a child can begin wearing hearing aids should be done before 3 months, only 7% of the respondents were able to answer correctlty, while 72% answered > 3 months, 3% answered as soon as possible, and the remaining 18% were unknown. The respondesnts were also asked to estimate the appropriate age on when to enroll a child with permanent hearing loss to early intervention services, 17 % were able to respond correctly that it should be done before 6 months, 38% said its > 6 months, 1 % answered before 1 year of age, 12% had no answer and 32% said it should be done ASAP (Table 4). The knowledge of the pediatricians regarding the causative conditions was assessed with multiple-choice question, “Which of the following conditions put a child at risk for permanent late-onset hearing loss?” Correct response in this question would be meningitis, > 48 hours NICU stay, history of CMV, congenital syphilis and family history of childhood hearing loss. 3% of the respondents were able to respond correctly, 92% have an incorrect response, and 5% had no answer. Table 5 summarizes the frequency of their responses. When the pediatricians were asked about the determining audiologic characteristics that qualify an infant for cochlear implantation, among the total number of respondents, 7% (4/60) correctly answered profound bilateral hearing loss, 70% (42/60) had incorrect answers, 17% (10/60) had no answer and 6% (4/60) were unsure. Thus, when the physicians were asked wether they believe there is a need for the each of the following components related to hearing loss (Table 9). Finally, the pediatricians were asked to rate their confidence in talking with parents regarding 5 specific topics (Table 4); 45% of the respondents are very confident, 53% are somewhat confident, and 2% are not confident. 18% are very confident in talking about the use of sign language versus auditory or oral communication. 52% and 30% are somewhat confident and not confident, respectively, with this aspect. With regards to talking to parents about consequences of unilateral or mild hearing loss, 29% are very confident, 63% are somewhat confident, and 8% are not confident. Moreover, with talking to parents about bilateral hearing loss of moderate to profound degrees, 27% are confident, 62% are somewhat confident, 10% are not confident, and 1% answered they are unsure of their confidence regarding this matter. In relating which infants may be candidates for cochlear implants, 15% are very confident, 43% are somewhat confident, 40% are not confident, and 2% are unsure of their confidence regarding this matter (Table 7). Discussion Our study shows that most pediatricians support the efforts for Newborn Hearing Screening – 90% deemed this very important. The 10% think that it is somewhat important and this may suggest a need for clearer understanding of the possible consequences of hearing loss on language development and learning. When asked whether training in medical school meets the needs of infants with permanent hearing loss, only 28% of the respondents consider their training as adequate. Majority of their sources of information about newborn hearing screening are educational meetings like lectures, seminars, and conventions. This is important in that recent lectures are more updated and together with the other resources such as journals, etc., are more readily accessible. Accessibility of such information is very valuable especially when most of our pediatricians do not frequently encounter or detect children with congenital hearing loss in their practice. Better understanding of newborn hearing screening and its advantages may improve the confidence of physicians in explaining the need and the process involved in the screening to parents. Our results showed that majority of pediatricians (62%) receive <50% of Newborn Hearing Screening results. This may suggest parents’ lack of knowledge of the importance of screening their babies for hearing loss so as to avoid life-long complications. The pediatricians also reported the need for further training in order to counsel parents better after making a diagnosis. 7% of our respondents answered that they were not at all confident about this. When asked if the screening causes added anxiety to parents, majority (57%) stated that it does not. However, a study by Young and Tattersall (2005) showed that it is more difficult to predict parents’ responses to failed or inconclusive screening results, which requires further screening. The study demonstrated the importance of a reassuring screening manner and this supports the need for training mentioned above. At least 50% of infants with congenital hearing loss have a genetic cause, according to Nance (2003). Therefore, our results stating that none of the respondents would refer to a geneticist after a confirmed permanent hearing loss suggest that there is a lack of understanding of the genetic issues associated with this. This understanding may also help in identifying secondary medical needs or disabilities. Also, a study performed by Nikolopoulos and associates (2006) indicated that approximately 4060% of deaf children also have ophthalmic problems, pointing to the need for immediate screening for ophthalmic problems and specialized ophthalmic examination once the diagnosis of deafness is confirmed. Visual acuity problems are also 2-3 times more prevalent in children with SNHL than in typically developing children. This suggests a need for ongoing developmental surveillance and regular ophthalmologic evaluations. Most of the pediatricians who responded know the specific conditions that would put a child at risk of late-onset NHL, which includes meningitis, >48hr NICU stay, history of CMV, congenital syphilis, and family history of childhood hearing loss. Because newborn hearing screening has not been mandated by the government or any professional medical organization in the Philippines, it has not been implemented in all hospitals in the government. When asked whether their hospital have an Early Hearing Detection and Intervention Program, only 30% answered the question correctly. It suggests that only a few pediatricians practice newborn hearing screening, and only a few are aware as to where the screening can be done. Hospitals which has a newborn hearing screening program should provide a more efficient and aggressive promotion of their program. Proper dissemination of information, with regards to screening, is a must in order for it to reach a wider population and produce more NBHS-aware pediatricians which in turn can help in informing the public of its importance. Price may be one of the major reasons why parents hesitate on having their babies undergo newborn hearing screening. Because parents are not part of our study, this speculation cannot be confirmed. As mentioned in the Results, the Department of Health has set a maximum rate of P550 for the newborn hearing screening, and the approximate price among Philippine hospitals is P400. However, some of the pediatricians were also unsure of the pricing and 37% even estimated the cost to be beyond P550. This may cause parents to assume that the screening is more expensive than it really is and may contribute to the low percentage of babies undergoing hearing screening. When asked to estimate the appropriate age on when to enroll a child with permanent hearing loss to early intervention services, only 17% were able to respond correctly, as seen in table 4. Results revealed that more emphasis should be placed on educating pediatricians about when a child can begin wearing hearing aids and also the proper age for enrollment in early intervention services. When faced with a diagnosis of permanent hearing loss, the pediatricians perceived 2 areas which were particularly challenging: (1) cochlear implants and (2) communication methods. It is important to know that not all children with hearing loss are candidates for cochlear implants. Also, pediatricians should be aware of the complexity of the decision-making process for the parents, as the technology in pediatric cochlear implantation is changing rapidly. A more informed and updated pediatrician with regards to the current practices in newborn hearing screening is a must in order to provide efficient screening. In the topic of communication methods, it is essential that families are well informed about all types of options as soon as possible after the diagnosis of permanent hearing loss is made to avoid delay in the child’s development. Information regarding the advantages and disadvantages of each option as well as its possible future complications should be part of the early intervention program. Limitations and Recommendations The study population was limited to the pediatric consultants practicing in the training hospitals within Quezon City. Thus, a larger and more randomized, possibly nationwide, hospital sampling is recommended to better reflect the current status of our pediatricians’ knowledge, attidues and practices about newborn hearing screening. Also, it is notable that out of the 126 survey forms distributed, only 60 were retrieved and some still had incomplete data. This was a result of not having a dedicated surveyor who would really wait for each and every pediatrician to answer the survey form up-front. Leaving the survey forms to the consultant’s secretary also negates the possibility of properly orienting the pediatric consultant about the importance of the study before he/she answers the survey. Ensuring a properly filled up survery form can further increase the significance of the study. Thus, improvement of the methods at which data can be more efficiently distributed and collected is imperative in order to increase the yields of the data collected and have a more significant sample. The researchers would also like to recommend that questions regarding the local guidelines for Newborn Hearing screening tests in the survey forms to further assess the knowledge of practitioners for the newborn hearing screening tests locally. Questions regarding the S.B. 2390 (AN ACT ESTABLISHING A UNIVERSAL NEWBORN HEARINGSCREENING PROGRAM FOR THE PREVENTION, EARLY DIAGNOSIS AND INTERVENTION OF HEARING LOSS AMONG CHILDREN) would also give a wider scope of area of knowledge to test. Conclusion On the basis of the results of this survey, we have made the following conclusions. There is evidence that Pediatricians support the efforts of Newborn Hearing Screening and its procedure. On the other hand, the down side of this is that there were still discrepancies in the knowledge of the pediatricians about the seriousness and consequences of hearing loss on language development and learning. These discrepancies on the facts of hearing loss which includes the risk factors for late-onset hearing loss, on when one should be subjected to the screening and on the issues of medical management, such as knowing when interventions should should take place, and when and where to refer infants for follow-up procedures, and for who are candidates for cochlear implants. We recommend for a more in depth awareness about Newborn Hearing Screening among Pediatricians. These knowledge gaps should be addressed through the primary sources of information regarding NBHS. Majority of the pediatricians resources are educational meetings which involves lectures, seminars and conventions. These may serve as venues for updates and discussions about Newborn Hearing Screening; altogether with the journals, which are easily accessible for such information to aid in the familiarity not only about Newborn hearing screening, but also hearing loss itself in order to put the pediatricians in a better position to support families on identification of infants with hearing loss and prevention of its consequences. Literature Cited Erenberg A, Lemons J, Sia C, Trunkel D, Ziring P. Newborn and infant hearing loss: detection and intervention.American Academy of Pediatrics. Task Force on Newborn and Infant Hearing, 1998- 1999. Pediatrics. Feb 1999;103(2): 527-30. Vohr BR, Carty LM, Moore PE, Letourneau K. The Rhode Island Hearing Assessment Program: experience with statewide hearing screening (1993-1996). J Pediatr. Sep 1998;133(3):353-7. Quintos, M.R., Isleta P.F., Chiong C.C., Abes G.T. 2003. Newborn hearing screening using the evoked otoacoustic emission: The Philippine General Hospital experience. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 34 Suppl 3:231-3. Olusanya BO, Ruben RJ, Parving A: Reducing the burden of communication disorders in the developing world: an opportunity for the millennium development project. JAMA 2006, 296:441-444. Yoshinaga-Itano C, Sedey AL, Coulter DK, Mehl AL: Language of early and later-identified children with hearing loss. Pediatrics 1998, 102:1161-171. Smith A, Mathers C: Epidemiology of infection as a cause of hearing loss. Infection and Hearing Impairment 2006, 31-66.] American Academy of Pediatrics (1999). Newborn and Infant Hearing Loss: Detection and Intervention. Task Force on Newborn and Infant Hearing. Pediatrics, 103, 527-530. JCIH. Year 2000 position statement: principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Joint Committee on Infant Hearing, American Academy of Audiology, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Speech-Language- Hearing Association, and Directors of Speech and Hearing Programs in State Health and Welfare Agencies.Pediatrics. Oct 2000;106 (4):798-817. Moeller, M., White, K., Shisler, L. 2006. Primary Care Physicians’ Knowledge, Attitude and Practices related to Newborn Hearing Screening. Pediatrics Official Journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. 118;1357-1370. http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/co ntent/full/118/4/1357 Retrieved on: August 16, 2008. Appendix A Tables and Figures Tables Characteristics n(%) N=60 Physician Gender Male 14 (23%) Female 39 (65%) Unknown 7 (12%) Experience with Pediatric Population 0-5 years 15 (25%) 6-10 years 11 (18.33%) 11-15 years 8 (13.33%) 15 onwards 18 (30%) Year of Birth 1950-1960 18 (30%) 1961-1970 12 (20%) 1971-1980 18 (30%) 1981-1990 3 (5%) Unknown 9 (15%) Table 1. Population 0-5 years 6-10 years 11-15 years 15 onwards Unknown With hearing loss 11 (73.33%) 8 (72.72%) 5 (62.5%) 8 (44.44%) 4 (50%) Without hearing loss 2 (13.33%) 2 (18.18%) 2 (25%) 6 (33.33%) 1 (12.5%) No Response 2 (13.33%) 1 (9.1%) 1 (12.5%) 4 (22.22%) 3 (37.5%) Table 2. Respondents’ number of years in practice and their encounter with patients with hearing loss 0-5 years 6-10 years 11-15 years 15 onwards Unknown > 50% Screening Results 2 4 2 5 2 <50% Screening Results 12 6 6 10 4 No Response 1 1 0 3 2 Table 3. Summary of the respondents years of practice with their received NBHS results a. NB who did not pass the hearing screening should receive additional testing b. A child can receive a definite diagnosis of NBHL < 1 mo *33 1-3 mos 15 4-6 mos 22 7-9 mos 2 10-11 mos 2 > 12 mos 7 > 24 mos 3 *17 *5 22 2 2 20 18 c. A child can begin wearing hearing aids d. A child with permanent hearing loss should be referred to early intervention *3 *5 *3 *5 7 *7 0 2 0 2 38 17 53 18 * Responses that are consistent with the Guidelines for Pediatric Home Providers (www.medicalhomeinfo.org) Table 4. Physician’s Estimates of Ages at which Follow-up Procedures should be Conducted (%) Meningitis* 93% >48hr NICU stay* 50% History of Cytomegalovirus* 87% Congenital Syphillis* 67% Family Hx of Childhood hearing loss* 83% Mother >40 at delivery 38% Congenital heart defect 37% Frequent Colds 48% Hypotonia 33% *Correct response; Table 5. Percentage of pediatricians who indicated specific conditions that would put a child at Risk of Late-Onset NHL Infant with profound bilateral hearing loss* Infant with bilateral mild-moderate hearing loss Infant with unilateral mild-moderate hearing loss Infant with unilateral profound hearing loss Unsure 67% (40/60) 48% (29/60) 25% (15/60) 43% (26/60) 6% (4/60) *the only correct response; percentage values reflect those who gave that answer over the total population Table 6. Percentage from the total number of respondents who Indicated conditions of hearing loss that will make an infant a candidate for cochlear implants Very Confident (%) 45 Somewhat Confident (%) 53 Not Confident (%) 2 Unsure (%) b. use of sign language vs. auditory or communication 18 52 30 0 c. consequences of unilateral or mild hearing loss 29 63 8 0 d. consequences of bilateral hearing loss 27 62 10 1 e. which infants are candidates for cochlear implants 15 43 40 2 a. causes of hearing loss Table 7. Physicians who are confident in talking to parents of child with permanent hearing loss Adequate Inadequate Unsure No answer Number 17 33 8 2 Percentage 28% 55% 13% 3% Table 8. Adequacy of Pediatric Training toward Infant Permanent Hearing Loss 0 Topic Methods of screening Protocol for follow-up screening Methods of screening children 0-5 during well-child visits Guidelines for informing families about screening results Impact of different degrees of hearing loss on infant language Early intervention options Guidelines for screening late onset hearing loss Useful contacts for more information Patient education resources Hearing aids and cochlear implants Genetics and hearing loss Great Need 50 (83%) 46 (77%) 50 (83%) 49 (82%) 51 (85%) 56 (93%) 53 (88%) 49 (82%) 49 (82%) 41 (68%) 42 (70%) Somewhat of a Need 10 (17%) 14 (23%) 10 (17%) 9 (15%) 9 (15%) 4 (7%) 7 (12%) 11 (18%) 11 (18%) 19 (32%) 18 (30%) Table 9. Pediatrician’s Perceptions About the Need for Training and/or Resources on Various Topics Figures Figure 1. Importance of NBHS (Question 5) Not Needed 2 (3%) 1 (2%) 8% ENT only Both ENT and Neurologist 92% Figure 2. Referals (Question 4) Unsure 3% Yes 40% No No 57% Figure 3. NBHS causes anxiety to parents (Question 6) Yes Unsure Figure 4. Primary sources for NBHS (Question 17) 7% Very confident 35% 58% Somewhat confident Not confident Figure 5. Explain NBHS process (Question 9) 18% 30% Correct Incorrect No answer 52% Figure 6. Asked if their hospital has NBHS (Question 18) Appendix B Modified Questionnaire Newborn and Infant Hearing Screening Program We need your help to evaluate the present state of newborn hearing screening programs in our country. Please take 15 minutes to tell us about your feelings and experiences. Your response will be completely confidential and would possibly be used to improve services for infants and young children with hearing loss. Your participation is greatly appreciated. Q1. Approximately what percentage of your practice is comprised of patients 0-5 years of age?__________ Q2.Approximately how many children with permanent hearing loss have you had in your practice during the past three years?__________ Q3.For newborns in your practice in year 2008, estimate the percentage for which you received newborn hearing screening results.__________ Q4.To whom you would routinely refer the family of a child with a confirmed hearing loss? ___Otorhinolaryngologist ___Neurologist ___Other pediatricians ___Others (specify) Q5. How important do you think it is to screen all newborns for permanent hearing loss? __Very important __Somewhat important __Somewhat unimportant __Very unimportant __Unsure Q6. Do you think hearing screening causes parents excessive anxiety and/or concern? __Yes __No __Unsure Q7. Estimate the approximate cost per baby for newborn hearing screening in the Philippines. _________(in pesos) Q8. Do you believe that the universal newborn hearing screening is worth what it costs? __Yes __No __Unsure Q9. How confident are you that you could explain the newborn hearing screening process to parents who have questions about the infant’s results? __Very confident __Somewhat confident __Not confident Q10. How confident are you in talking to parents of a child with permanent hearing loss about… Very Somewhat Not confident confident confident a. Causes of hearing loss?-----------------------------------------------------b. Use of sign language vs. auditory/oral communication?-----------c. Consequences of unilateral or mild hearing loss?--------------------d. Consequences of bilateral hearing loss of moderate to profound degrees?--------------------------------------------------------- e. Which infants may be candidates for cochlear implants?---------- Q11. Did your training prepare you adequately to meet the needs of infants with permanent hearing loss? __Yes __No __Unsure Q12. For each item below, please indicate the level of need you believe physicians have for that type of information related to permanent hearing loss in children. Great need Somewhat Not needed of a need a. Methods for screening---------------------------------------------------------b. Protocol for follow-up screening--------------------------------------------c. Methods of screening children 0-5 during well-child visits-----------d. Guidelines for informing families about screening results-----------e. Impact of different degrees of hearing loss on infant language-----f. Early intervention options-----------------------------------------------------g. Guidelines for screening late onset hearing loss------------------------h. Useful contacts for more information-------------------------------------i. Patient education resources--------------------------------------------------j. Hearing aids and cochlear implants-----------------------------------------k. Genetics and hearing loss-----------------------------------------------------l. Other (describe)___________________________________ Q13. What is the best estimate of the earliest age at which: (Enter age estimate) a. A newborn not passing the hearing screening should receive additional testing:__________ b. A child can be definitely diagnosed as having a permanent hearing loss:__________ c. A child can begin wearing hearing aids:__________ d. A child with permanent hearing loss should be referred to early intervention services:__________ Q14. Which of the following conditions put a child at risk for permanent late onset of hearing loss? (check all that apply) __meningitis __mother over age 40 __frequent colds __congenital heart disease __hypotonia __history of cytomegalovirus (CMV) __>48 hours in NICU __congenital syphilis __cleft palate __family history of childhood hearing loss Q15. Which of the following infants may be a candidate for cochlear implants? (check all that apply) __infant with bilateral mild-moderate hearing loss __infant with profound bilateral hearing loss __infant with unilateral mild-moderate hearing loss __infant with unilateral profound hearing loss __unsure Q16. How informed do you think you are about issues related to permanent hearing loss? Very Somewhat Somewhat Uninformed Informed a. The incidence of hearing loss among newborns/infants----b. Procedures for newborn/infant hearing screening-----------c. Consequences of unilateral/mild hearing loss-----------------d. Consequences of bilateral severe or profound hearing losse. Medical interventions (e.g. cochlear implants)------------------ Informed Uninformed f. Audiological interventions (e.g. hearing aids)-------------------g. Educational interventions for hearing loss----------------------h. Genetics of hearing loss---------------------------------------------- Q17. What has been your primary source of information about newborn hearing screening? ___________________________________________________________________________________ _ Q18. Does your hospital have an Early Hearing Detection and Intervention Program? __Yes __No __Unsure Q19. Please list below any other concerns you have about newborn hearing screening, diagnosis, and intervention. _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________ Please tell us about yourself: Type of practice: __Pediatrician __OB/GYN __Family Practice Physician __Neonatologist __Otolaryngologist __Other (specify)__________ Practice setting: (where you spend most of your time) __Hospital setting __Medical school or parent university __Other (specify)__________ Gender: __Male __Female Year of birth:________ Years of practice with pediatric population:__________ Thank you! Appendix C Training Hospitals in Quezon City 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. AFP Medical Center Capitol Medical Center Dr. Fe del Mundo Medical Center De Los Santos Medical Center FEU – NRMF East Avenue Medical Center Jesus Delgado General Hospital National Children’s Hospital Philippine Children’s Medical Center Philippine Heart Center Quezon City General Hospital Quirino Memorial Medical Center St. Luke’s Medical Center UERMMMC United Doctor’s Hospital Veteran’s Memorial Medical Center World Citi Medical Center