A Field Experiment

advertisement

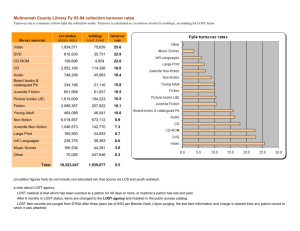

Decision-Making Training for Occupational Choice and Early Turnover: A Field Experiment Asya Pazy, Yoav Ganzach, and Yariv Davidov School of Business, Tel Aviv University Published in: Career Development Internationa (2006), 11, 80-91 Correspondence address to Asya Pazy, The Leon Recanati Graduate School of Business Administration, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel. asyap@post.tau.ac.il 2 Abstract Purpose – The study examined how a short intervention, aimed at enhancing occupational choice skills, influenced turnover during early stages of organizational membership. It explored two theoretical rationales for this effect, social exchange and self-determination. Methodology – The study is a "constructive replication" of previous research, and it employed a similar field experimentation methodology. Groups of candidates in the Technical School of the Israeli Air Force were randomly assigned to experimental (Decision Making Training) and control groups. Perceived Organizational Support and turnover were measured at two points in time. Findings – The results showed that the intervention reduced turnover (relative to a control group) as measured at two points in time – at the end of a technical training program and six months later into their military service. Perceived Organizational Support was not enhanced by the intervention. The experimental results were consistent with the self-determination explanation more than with the social exchange explanation. Practical implications - The practical benefits of Decision Making Training during early encounters with the organization are discussed. Decision Making Training is recommended as an effective tool during the career exploration phase, to facilitate the integration of self and environment awareness and to enhance self-determined career goals. Keywords – turnover, career management, early career, self determination, social exchange. Classification – research note. 3 New entrants are highly responsive to organizational influence during their initial encounters with the organization. The relative confusion and disorientation that characterize this phase increase their susceptibility to cognitive-informational cues as well as to emotional and social support cues (e.g., Louis, 1980; Morrison, 1993; Ostroff & Kozlowski, 1992). The majority of studies that examined organizational entry interventions have focused on the cognitiveinformational aspects of these interventions, and confirmed the benefits of providing accurate information early on. Considerable research shows that the Realistic Job Preview (termed RJP) results in increasing commitment and reducing turnover (for reviews, see Meglino, Ravlin, & DeNisi, 2000; Phillips, 1998). However, the non-informational aspects of early organizational encounters are also important (Wanous & Reichers, 2000). Information-free interventions were found to be similarly effective to the Realistic Job Preview. For example, Buckley, Fedor, Veres, Wiese, & Carraher (1998) showed that the benefits of an orientation program that focused on new entrants’ tendency to inflate their early expectations and did not include any job information, were similar to those of the informational (RJP) approach (Buckley, Mobbs, Mendoza, Novicevic, Carraher-Shawn, & Beh , 2002). Another information-free intervention (called Decision Making Training, or DMT) was similar to the Realistic Job Preview in its short-term increase of commitment (Ganzach, Pazy, Ohayun & Brainin, 2002). DMT is a short program that helps new entrants to enhance their skills in the usage of an occupational decision strategy. The purpose of the present study is to examine the effectiveness of this information-free intervention in increasing occupational commitment and reducing turnover among new entrants during the early phase of their organizational career. An indication for such effectiveness was found in a previous study which examined cognitive-informational and socio-emotional aspects 4 of various early phase interventions. While focusing primarily on RJP, a serendipitous finding indicated that, though DMT and RJP had a similar short-term effect on commitment, DMT was superior to RJP in its long-term effect (Ganzach et al, 2002). The present study focuses solely on the DMT intervention. It aims to provide further evidence for the effect of DMT on occupational commitment and to examine the theoretical rationale for this effect. From a practical viewpoint, DMT promises several organizational and individual advantages over information-based methods like RJP. First, DMT is an off-the-shelf, prepackaged program. As a content-free, skill-enhancing intervention, it is not tailored to specific occupations or jobs in specific settings, and therefore does not require prior job analysis. RJP, on the other hand, describes specific jobs and therefore requires a careful, situation-specific collection of accurate data. Such an analysis is costly and time consuming, and often – because of the flexible and changing character of many jobs – unfeasible (Cardy & Dobbins, 1986). Second, RJP may not be suitable when recruitment is aimed at an overall fit with organizational culture rather than a fit with a specific job (Bowen, Ledford, and Nathan, 1991). Being neither a job- nor an organization- specific intervention, DMT offers flexibility and economy of scale in addressing the recruitment needs of organizations. Third, evidence from Ganzach et al (2002) indicates that, in the long run, the effectiveness of DMT in reducing turnover and maintaining occupational commitment is more enduring than that of RJP. Finally, from the individual employee point of view, DMT is a useful tool in the career exploration phase. It helps in the integration of self and environment awareness, which, when properly managed, results in personally effective goal setting (Greenhaus, Callanan, & Godshalk, 2000). Theoretical considerations: From a theoretical viewpoint, two different rationales might account for the effect of DMT on turnover and commitment: Social exchange and self- 5 determination. In terms of social exchange, the provision of DMT conveys concern. It seems to be an indication that the organization cares about new entrants' ability to make occupational choices that are personally appropriate for them, and that it actively supports the development of this ability. Through a social exchange process, the perception of organizational support induces reciprocation in the form of increased commitment to the party that initiated the exchange (Blau, 1964), and, as a result, decreases turnover. Abundant research shows a variety of positive attitudinal and behavioral outcomes that result from a perception of organizational support (Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison, & Sowa, 1986; Eisenberger, Cummings, Armeli, & Lynch, 1997; for a review, see Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). The social exchange argument is also compatible with the view of training and development activities as benefits that contribute to commitment and to willingness to remain with the organization (Bartlett, 2001; Birdi, Allen, & Warr, 1997; Gaertner & Nollen, 1989; Lee & Bruvold, 2003; Meyer & Smith, 2000; Nordhaug, 1989). In sum, according to the social exchange rationale, DMT increases Perceived Organizational Support, which in turn enhances commitment and reduces turnover. The second explanation is based on the theory of self-determination. Social contexts that support autonomous forms of self-regulation maintain and enhance intrinsic motivation; self determined motivation prevents dropout (Ryan & Deci, 2002; Vallerand, Fortier & Guay, 1997). According to this theoretical explanation, DMT reduces turnover through the binding effect of choice behavior. The priming of volitional choice behavior, which is induced by DMT, enhances commitment to the chosen course of action by a post-decisional dissonance reduction process (Festinger, 1957). The long-term impact of DMT is the behavioral persistence that ensues from free choice (Comer & Laird, 1975; O’Reilly & Caldwell, 1981) and self-determination (Mossholder, 1980; Zuckerman, Porac, Lathin, Smith & Deci, 1978). 6 Incidentally, the theoretical rationale in Ganzach et al study was originally based on social exchange, and self determination emerged ex post facto. Its results were not sufficient to determine the relative validity of the two rationales, as their overall pattern lent partial support to both1. In addition, the construct of Perceived Organization Support, the hypothesized mediator of social exchange, was inferred, rather than measured, in that study. The present field experiment is designed as a “constructive replication” (Eden, 2002; Lykken, 1968) of one part of the previous study. By keeping the context – a military setting – constant, but altering three significant aspects of the previous study, a replication can strengthen confidence in the benefits of this intervention. The research hypothesis is that the provision of DMT at an early phase of organizational career will decrease turnover compared to a control group. The hypothesis derived from the social exchange model predicts that this effect will be mediated by Perceived Organizational Support, while the self determination model predicts a direct effect. Method In a constructive replication, the same hypothesized relationships among the same theoretical constructs are tested, while varying their operationalization. We varied three such aspects. 1 The stronger initial commitment among participants immediately after they received the DMT compared to control participants was consistent with social exchange, but not compatible with self-determination. A selfdetermination model suggests differences in commitment later, as adherence to a decision is manifested after people have encountered difficulties associated with their job. On the other hand, the self-determination explanation was consistent with the lower turnover in the DMT compared to control groups (and to an RJP group), twenty months after the intervention. At such a late time, reciprocation in exchange to an initial gesture is no longer relevant, but lower turnover could be interpreted as adherence to an autonomously made choice in the face of difficulties encountered along the way. Thus, the latter result was compatible with the self-determination view and incompatible with the social exchange view Ganzach et al, 2002). 7 First, we varied the timing of the DMT provision and of its outcome measurement. In the Ganzach et al study DMT was administered eight months prior to entering the organization. The relatively long period that elapsed between the intervention and entry might have obscured a sense-making interpretation. In the present study DMT is administered a few weeks after organizational entry, upon entry into the particular route of training, and its effect is measured twice, after 4 months and 10 months. Second, whereas the sample in the previous study was drawn primarily from a highly motivated population, the present sample is drawn primarily from the lower end of the population, in terms of prior attitudes towards the organization. The dynamics of reducing turnover among recruits whose initial level of commitment is low might be qualitatively different than that needed to boost growing levels of commitment (Bretz & Judge, 1998). Third, by measuring an additional variable, Perceived Organizational Support, the present study can better distinguish between social exchange and self-determination. The social exchange explanation suggests that the influence of DMT on turnover depends on enhanced Perceived Organizational Support. On the other hand, the self-determination explanation suggests that the provision of DMT reduces turnover without necessarily increasing the perception of support. Context and Procedure The study was conducted in the technical school of the Israeli air force. The Israeli Defense Forces requires that all candidates for military service go through an assessment process in order to determine their physical, mental and motivational profiles prior to their enlistment. Based on these profiles, the higher part of (male) candidates is usually assigned to combat 8 service, and the lower part – to support unit service. The sample of this study – candidates for technical support in the air force – was drawn from the latter. A small percentage of these candidates are vocational high school graduates. Among certain vocational high schools, motivation for military service might be higher (Harel & Baruch, 1993) Several weeks after their enlistment and basic training, candidates for technical occupations participate in an "orientation and assessment week" in the technical school of the air force. They are then admitted to training programs that last from one to five months (three months on average). Upon completion of training, they serve in technical support, electronics, or other maintenance–related jobs in an air force base. The training programs, as well as the military technical service, are considered quite demanding. It is also important to note that though military service in Israel is compulsory, there is a considerable degree of freedom of choice as to where, and for how long, technical staff serve in various jobs and units. Also, technical training and service in technical jobs in the army are often seen as an early phase of a technical career. The experiment took place during the orientation and assessment week. During this week candidates take aptitude tests, respond to attitude surveys, and receive information about a variety of air force jobs and occupations. At the end of the week they choose and rank their three top preferences out of a list of 20 or more technical support, electronics, or maintenance occupations. The experimental manipulation (a DMT workshop) was administered to randomly selected groups towards the end of the week, after receiving occupational information and before making occupational choices (on a special Preference Form). The experimental manipulation. The DMT intervention adopts a compensatory occupational choice approach (Osborn, 1990). It presents a systematic decision-making strategy. 9 In a sequence of five steps participants learn to: (1) Define the various alternatives; (2) Identify attributes that are relevant to the decision; (3) Evaluate the importance of each attribute; (4) Weigh the alternatives on each attribute, and (5) Arrive at an overall evaluation of each alternative by calculating a weighted average of the attributes values, with weights indicating importance (Feldman & Whitcomb, 2005; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Janis & Mann, 1977; Sauermann, 2005). After learning the principles of the method, participants practiced its principles in a car choice exercise. They were then advised to use the new method soon, when choosing Air Force occupations. See Appendix 1 for the DMT instructions. The DMT intervention was administered to randomly selected groups (of 20-25 participants at a time). It was led by air force personnel, and lasted about an hour and a half. The control participants were engaged in a standard questionnaire filling activity for a similar duration. Sample A full cohort of candidates for technical training participated in this study. The sample consisted of 466 soldiers (18-20 years old). Of these, 247 were in the DMT condition and 219 in the control (no DMT) condition. The majority (88.5%) was male, similar to the gender proportion in the technical air force population. The experimental and control conditions were similar in motivational and mental profiles, as routinely measured in the organization prior to enlistment [t (464) =0.55 for the motivational profile, and t (464) =0.20, for the mental profile]. 10 Measures Perceived Organizational Support (POS) was measured by eight (7-point scale) items from Eisenberger et al (1986) translated to Hebrew. A sample item is: "The army really cares about the soldier's well being". Two items were omitted due to their irrelevance to the military context. Alpha Cronbach was 0.76 Program Turnover. This binary variable indicates whether the participant dropped from the technical training program or completed it. Note that these programs range from one to five months. Reasons for dropping mostly relate to low motivation, lack of interest, or other kinds of misfit. Occupation Turnover. This binary variable indicates whether, six months after completion of training, the participant dropped from his/her occupation, or stayed and completed his service within this occupation. Note that this measure is statistically independent from Program Turnover. Results The percentages of the dependent variables – the two kinds of turnover – and the means (standard deviations) of Perceived Organizational Support are presented in Table I by experimental condition. ------------------------------Take in Table I about here ------------------------------Supporting our prediction, the results show that Program Turnover in the DMT condition was lower than in control, indicating a large effect of DMT on turnover – a decrease of about a 11 third. Despite the low power of χ2 in detecting differences in proportions that deviate from 50%, the difference between Program Turnover in the two groups was significant, χ(1)2=4.2, p<0.05. Six months after completion of training, Occupation Turnover among the programs’ graduates – a statistically independent measure for the effect of the experimental manipulation was considerably lower in the DMT group compared to control (1.9% versus 4.2%). However, the difference did not reach statistical significance (perhaps because of the overall low levels of Occupation Turnover2). On the other hand, we did not find a significant difference in Perceived Organizational Support between the DMT and the control group, t(443) =0.7. Discussion The present study provides further evidence to the usefulness of a simple intervention that reduces early turnover. We found that a structured opportunity to reflect upon occupational options via decision training results in stronger adherence among new entrants to their choice and reduced turnover. This finding is now generalized to a different population in terms of prior motivational profile (its lower end) and to different intervention timing, though further research is certainly needed to generalize it to non-military settings and to other kinds of organizational contexts and occupations. From a theoretical standpoint, the results of this study are not consistent with the social exchange rationale. The predicted elevation in Perceived Organizational Support among participants who participated in the DMT was not supported. On the other hand, the results are consistent with the self-determination rationale. The stronger behavioral perseverance of the Note that if the ‘true’ effect of the experimental manipulation is reducing Occupation Turnover from 4.2% to 1.9%, the sample size needed to reject the null hypothesis with p<0.05 is about 7500. 2 12 DMT participants can be accounted by post decisional influence that justify prior choice. DMT participants were presumably more conscious of their choice process. Aligning their attitude to their awareness that their own choice had led them to this program, the DMT participants persevered in the face of hardships. This interpretation is in line with the view of behavior as shaping future attitudes and actions, and of people as engaging in retrospective processes of selfjustification (Brockner, 1992; Salancik, 1977; Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978). In the context of organizational entry, this view suggests that the manner in which a job choice decision is made affects the decision maker’s subsequent behavioral commitment (see also O’Reilly & Caldwell, 1981). Two points need to be made with regard to retrospective justification in these circumstances. First, self-determination is especially relevant when expressed desires are fulfilled. If one gets the assignment that one has reflectively chosen, one becomes more committed, retrospectively, to this assignment (compared to a non-reflective, unaware chooser). On the other hand, when assignment is inconsistent with choice, there is no reason to expect retrospective binding or commitment. In fact, based on the escalation of commitment literature, we might even expect reduced commitment among reflective compared to non-reflective choosers, as a way to retrospectively justify what one did not get (Schoorman, 1988; Schoorman & Holahan, 1996; Staw, 1981). For technical constraints that are common in field studies, we could not analyze the turnover data separately according to the degree to which single preferences had been met, but in future research such an analysis is needed in order to further clarify the self-determination explanation. Second, the supportive evidence that favors the self-determination over the social exchange interpretation should lead to a careful re-definition of the construct that underlies the 13 DMT effect. The obtained higher perseverance in this study should be viewed as stronger commitment to a course of action, or as commitment to professional training, rather than as organizational commitment, which the social exchange argument had predicted. Our evidence rules out an alternative (prospective) explanation, according to which the lower turnover among the DMT participants was caused by more desirable assignments and better person – job fit. First, the two groups did not differ in the degree of correspondence between the participants’ top preferences (as marked on the Preference Form) and the actual job that they eventually received (χ (1)2 =0.052). On average, 64% of participants in this sample were assigned to one of their three top choices. Second, mean assignment satisfaction (a measure that was obtained during the first days of training program, after the assessment week) was similar for the two groups [t (462) =0.61]. However, our evidence at this point cannot rule out the possibility that the choices of the DMT participants were more appropriate for them, so that among those that did get what they wanted, there might have been a better person - job fit (e.g., Chen, Chang, & Yeh, 2004; Wolniak & Pacarella, 2005). Returning to the social exchange explanation, the lack of support for this explanation in the present study does not contradict the operation of social exchange processes in employment contexts in general (Birdi et al 1997; Gaertner & Nollen, 1989; Nordhaug, 1989), and during organizational entry in particular (Ganzach et al 2002; Meglino, DeNisi, & Ravlin, 1993; Meglino, DeNisi, Youngblood, & Williams, 1988). The lack of significant elevation in Perceived Organizational Support among the DMT participants in the present study might be an indication for the robustness of POS among the entire pool of participants. A single organizational gesture might not be enough to alter the perception of that organization. The perception of organizational support in this study was probably shaped by the first few weeks of service, in which the DMT 14 was but one event. It is possible that a short DMT intervention might be more effective in enhancing POS when it occurs prior to any substantial contact with the employer (as was the case in the Ganzach et al study). Finally, an important implication of this study is that encouraging the initial reflection and deliberation of new entrants regarding their own direction in the organization, holds promise of getting a more committed workforce. According to the career management literature, increased awareness of self and of alternative occupations leads to more effective goal setting (e.g., Greenhaus et al, 2000), which, at an early career phase, involves a well-thought decision to enter a particular occupation. The DMT tool supports this process. The results of this and the previous study suggest that its provision increases commitment to the chosen goal. It is therefore recommended to consider DMT-type programs as an addition to early socialization practices. 15 References Bartlett, K. (2001), "The relationship between training and organizational commitment: A study in the health care field," Human Resource Development Quarterly, 12,335-352. Birdi, K., Allan, C., & Warr, P. (1997), "Correlates and perceived outcomes of four types of development activity," Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 845-857. Blau, P.M. (1964), Exchange and power in social life, John Wiley, New York. Bowen, D.E., Ledford, G.E., & Nathan, B.R. (1991), "Hiring for the organization, not for the job," Academy of Management Executive, 5, 35-51 Bretz, R. D., & Judge, T. A. (1998), "Realistic job preview: A test of the adverse self-selection hypothesis," Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 330-337. Brockner, J. (1992), "The escalation of commitment to a failing course of action: Toward theoretical progress," Academy of Management Review, 17, 39-61. Buckley, M.R., Fedor, D.B., Veres, J.G., Wiese, D.S., & Carraher, S.M. (1998), "Investigating newcomer expectations and job-related outcomes," Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 452-461. Buckley, M.R., Mobbs,T.A., Mendoza,J.L., Novicevic, M.M., Carraher, S.M. & Beu, D.S. (2002), "Implementing realistic job previews and expectation-lowering procedures: A field experiment," Journal-of-Vocational-Behavior, 61, 263-278. Cardy, R.L., & Dobbins, G.H. (1986), "Affect and appraisal accuracy: Liking as an integral dimension in evaluating performance," Journal of Applied psychology, 71, 672-678. Chen, T.T., Chang, P.L., and Yeh, C.W. (2004), "A study of career needs' career development programs, job satisfaction and the turnover intentions of R&D personnel, "Career Development 16 International, 9, 424-437. Comer, R. & Laird, J.D. (1975), "Choosing to suffer as a consequence of expecting to suffer: Why do people do it?" Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35, 459-477. Eden, D. (2002), "Replication, meta-analysis, scientific progress, and AMJ’s publication policy," Academy of Management Journal, 45, 841-846. Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986), "Perceived organizational support," Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 500-507. Eisenberger, R., Cummings, J., Armeli, S., & Lynch, P. (1997), "Perceived organizational support, discretionary treatment, and job satisfaction," Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 812-820. Feldman, D.C., & Whitcomb, K.M. (2005), "The effects of framing vocational choices on young adults' sets of career options," Career Development International, 10, 7-25. Festinger, L.A. (1957), A theory of cognitive dissonance. Standford University Press, Stanford. Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, J. (1975), Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA. Gaertner, K., & Nollen, S. (1989), "Career experience, perceptions of employment practices, and psychological commitment to the organization," Human Relations, 42, 975-991. Ganzach, Y., Pazy, A. Ohayun, J., & Brainin, E. (2002), "Social exchange and organizational commitment: Decision-making training for job choice as an alternative to the Realistic Job Preview," Personnel Psychology, 55, 613-637. Greenhaus, J.H., Callanana, G.A., and Godshalk, V.M. (2000), Career management, Dryden Press, Fort Worth. 17 Harel, G., & Baruch, Y. (1993), "The effect of educational background on performance and organizational commitment," Human resource Management Journal, 3, 78-87. Janis, I.L., & Mann, L. (1977), Decision making, Free Press, New York. Klein, H. J., & Weaver, N. A. (2000), "The effectiveness of an organizational-level orientation training program in the socialization of new hires," Personnel Psychology, 53, 1, 47-66. Lee, C.H., & Bruvold, N.T. (2003), "Creating value for employees: Investment in employee development," International Journal of Human Resource Management, 14, 981-1000. Louis, M.R. (1980), "Surprise and sense making: What newcomers experience in entering unfamiliar organizational settings," Administrative Science Quarterly, 25, 226-251. Lykken, D.T. (1968), "Statistical significance in psychological research," Psychological Bulletin, 70, 151-159. Meglino, B.M., DeNisi, A.S., & Ravlin, E.C. (1993), "Effects of previous job exposure and subsequent job status on the functioning of a realistic job preview," Personnel Psychology, 46, 803-822. Meglino, B.M., DeNisi, A.S., Youngblood, S.A., & Williams, K.J. (1988), "Effects of realistic job previews: A comparison using an enhancement and a reduction preview," Journal of Applied Psychology, 73, 259-266. Meglino, B.M, Ravlin, E.C., & DeNisi, A.S.(2000), "A Meta-analytic examination of Realistic Job Preview effectiveness: A test of three counterintuitive propositions," Human Resource Management Review, 19, 407-434. Meyer, J., & Smith, C. (2000), "HRM practices and organizational commitment: Test of a mediation model," Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 17, 319-331. 18 Morrison, E.W. (1993), "Longitudinal study of the effect of information seeking on newcomer socialization," Journal of Applied psychology, 78, 173-183. Mossholder, K.W. (1980), "Effects of externally mediated goal setting on intrinsic motivation: A laboratory experiment," Journal of Applied Psychology, 65, 202-210. Nordhaug, O. (1989), "Reward functions of personnel training," Human Relations, 42, 373-388. Osborn, D.P. (1990), "A reexamination of the organizational choice process," Journal of Vocational Behavior, 36,45-60. O’Reilly, C.A., & Caldwell, D.F. (1981), "The commitment and job tenure of new employees: Some evidence of postdecisional justification," Administrative Science Quarterly, 26, 597-616. Ostroff, C., & Kozlowski, S.W. (1992), "Organizational socialization as a learning process: The role of information acquisition," Personnel Psychology, 45, 849-874. Phillips, J.M (1998), "Effects of realistic job previews on multiple organizational outcomes: A meta-analysis," Academy of Management Journal, 41, 673-690. Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002), "Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature," Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 698-714. Ryan, E.L., & Deci, E.L. (2002), "An overview of Self-Determination Theory: An organismicdialectical perspective," In Deci, E.L., and Ryan, R.M. (Eds.), Handbook of selfdetermination research, The University of Rochester press, New York, pp.3-37. Salancik, G.R. (1977), "Commitment and the control of organizational behavior and belief," In Staw, B. & Salancik, G. (Eds.), New directions in organizational behavior, St. Clair, Chicago, pp. 1-54. 19 Salancik, G.R., & Pfeffer, J. (1978), "A social information processing approach to job attitude and task design," Administrative Science Quarterly, 23, 224-253. Sauremann H. (2005), "Vocational choice: A decision making perspective," Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66, 273-303. Schoorman, F.D. (1988), "The escalation bias in performance appraisals: An unintended consequence of supervisor participation in hiring decision," Journal of Applied psychology, 73, 58-62. Schoorman, F.D. & Holahan, P.J. (1996), "Psychological antecedents of escalation behavior: Effects of choice, responsibility, and decision consequences," Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 786-794. Staw, B.M. (1981), "The escalation of commitment to a course of action," Academy of Management Review, 6, 577-587. Vallerand, R.J., Fortier, M.S., and Guay, F. (1997), "Self-determination and persistence in reallife setting: Toward a motivational model of high school dropout," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 1161-1176. Wanous, J. P., & Reichers, A. E. (2000), "New employee orientation programs," Human Resource Management Review, 10, 435-451. Wolniak, G.C., & Pascarella, E.T. (2005), "The effects of college major and job field congruence on job satisfaction," Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67, 233-251. Zuckerman, M., Porac, J., Lathin, D., Smith, R., & Deci, E. (1978), "On the importance of selfdetermination for intrinsically motivated behavior," Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 4, 443-447. 20 Table I Turnover Data and Means ( Standard Deviations) of Perceived Organizational Support Condition DMT Control (n=247) (n=219) Program Turnover 15.4%* 22.8% Occupation Turnover 1.9% 4.1% Perceived Organizational Support 3.99 3.95 (0.96) (0.91) *p < 0.05 21 APPENDIX 1: THE DECISION MAKING TRAINING WORKSHOP The text used by the air force person who conducted the DMT workshops: “The purpose of this workshop is to help you make a decision concerning your preference for your technical training and job during your service in the air force. We do not intend to influence what you decide. We want to help you improve the process by which you make decisions. We will teach you a decision-making procedure, which can help you in making decisions in general, and decisions regarding your military service in particular. The workshop consists of 2 stages: 1. General description of the balance-sheet method, 2. applying this method to an example car choice. The method we present is a way to make decisions in the best possible way. It is based on the construction of a balance sheet, in which a person assesses the existence of personally important considerations in each of the alternatives considered.” Instructions for the the Balance Sheet Method: “Below is the sequence of recommended steps. Make sure you work through them in the order specified: 1. Initial definition of all relevant considerations: Think about various considerations in the present decision situation. Be sure to include as many relevant considerations as possible. Do it with an open mind – the more relevant considerations elicited, the more effective the process. 2. Delete insignificant considerations: A long list might make the process cumbersome; at this stage we recommend limiting the list to the considerations which are personally important to you. 3. Assess the importance of each consideration: Now you have to determine the extent to which each consideration is important to you. Rate each parameter on a 0 (not important at all) to a 100 (extremely important) scale. 4. Define the alternatives under consideration, the alternatives among which you would like to choose. Focus on alternatives that are real for you, rather than on alternatives that are unfeasible. 5. Check the applicability of each consideration to each alternative. Examine the extent to which each consideration exists within each alternative, and rate it on a 0 (does not apply at all) to 5 (very much applies) scale. 6. Calculate the overall value of each alternative: Multiply the importance score of each consideration by the score indicating the degree to which it applies to an alternative, and then add up the product values for each alternative. 7. Choose the highest value alternative: If you have done the process right, the alternative with the highest number is the one you prefer most. When two alternatives have equal sum, it means that they are almost equivalent to you. In order to choose between them, you have to add considerations and then repeat the above procedure.” Instructions for the car choice trial exercise with the balance sheet method: “We will use this method for a trial example. Consider the 3 used cars described below (description follows). Their price is similar. Apply the balance sheet method to the task of choosing one out of these three cars.”