GEOS 204, LAB 4: INTRODUCTION TO FIELD MAPPING

advertisement

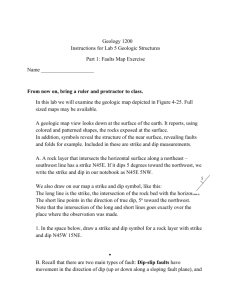

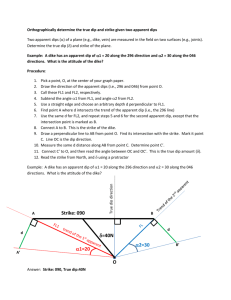

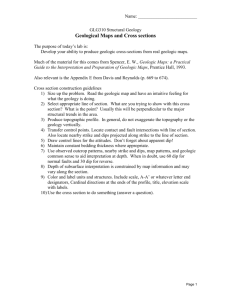

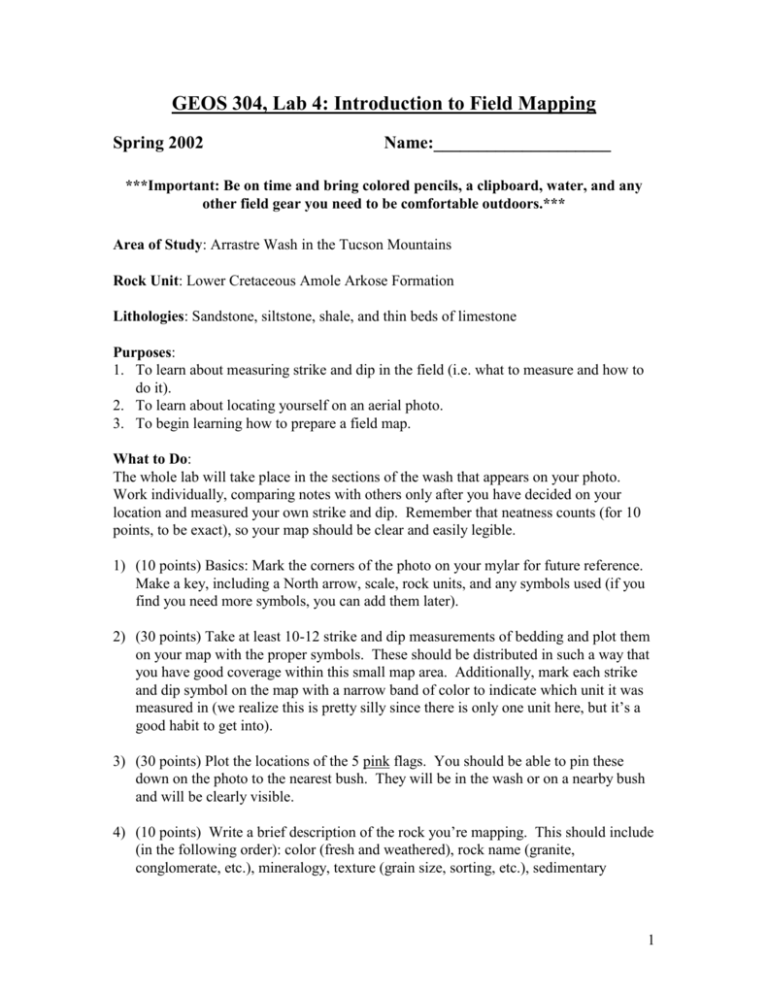

GEOS 304, Lab 4: Introduction to Field Mapping Spring 2002 Name:____________________ ***Important: Be on time and bring colored pencils, a clipboard, water, and any other field gear you need to be comfortable outdoors.*** Area of Study: Arrastre Wash in the Tucson Mountains Rock Unit: Lower Cretaceous Amole Arkose Formation Lithologies: Sandstone, siltstone, shale, and thin beds of limestone Purposes: 1. To learn about measuring strike and dip in the field (i.e. what to measure and how to do it). 2. To learn about locating yourself on an aerial photo. 3. To begin learning how to prepare a field map. What to Do: The whole lab will take place in the sections of the wash that appears on your photo. Work individually, comparing notes with others only after you have decided on your location and measured your own strike and dip. Remember that neatness counts (for 10 points, to be exact), so your map should be clear and easily legible. 1) (10 points) Basics: Mark the corners of the photo on your mylar for future reference. Make a key, including a North arrow, scale, rock units, and any symbols used (if you find you need more symbols, you can add them later). 2) (30 points) Take at least 10-12 strike and dip measurements of bedding and plot them on your map with the proper symbols. These should be distributed in such a way that you have good coverage within this small map area. Additionally, mark each strike and dip symbol on the map with a narrow band of color to indicate which unit it was measured in (we realize this is pretty silly since there is only one unit here, but it’s a good habit to get into). 3) (30 points) Plot the locations of the 5 pink flags. You should be able to pin these down on the photo to the nearest bush. They will be in the wash or on a nearby bush and will be clearly visible. 4) (10 points) Write a brief description of the rock you’re mapping. This should include (in the following order): color (fresh and weathered), rock name (granite, conglomerate, etc.), mineralogy, texture (grain size, sorting, etc.), sedimentary 1 structures (planar laminations, cross-bedding, etc.), and outcrop characteristics (ledgeforming, cliff-forming, etc.). 5) (10 points) Plot the locations and orientations of the four fold hinges, using the appropriate symbols. 6) BONUS (10 points) We haven't yet talked about cross-sections, but we will spend lots of time on them in future labs. Sketch a cross-section of one or more of the structures you mapped. See Davis & Reynolds p 669-673 for information on crosssections. Useful Advice 1) Location: This is often half the battle in mapping. You can take the best measurements the world has ever seen but if you plot them in the wrong locations on your map, then all you’ve produced is a work of fiction (and not one that will be any threat to Tom Clancy, either). So how do you locate yourself on the photo? There’s no one way and what you use will depend largely on what you have to work with but here are some ideas: A) Start at some obvious landmark that shows up clearly on the photo, like major fork in the wash. Note the bearing (compass direction) of each leg of the fork on your map and make sure those agree with what you observe in the field. B) Now that you know where you are, the goal is to move up the wash without losing track of your location. With this in mind, look around and try to correlate some other features around you with ones on the photo. You should be able to pick out individual bushes. This is how to confirm your location. C) Before you move: Look up the wash and pick out a point that you’re going to walk to. Find that point on the map. This may only mean going to the farthest bush you can identify or it may mean going to a bend in the wash. It will also help to pay attention to the bearing of the wash. D) The key is keeping track of where you are. If you get lost, go back to a known point and start again. Above all, take your time. This is not a quick process. 2) Strike and Dip: For the purposes of this exercise, you will be measuring strike and dip of bedding planes--the interfaces between rock layers. These will be defined by a change in the rock type or mineralogy across the plane. Beware! There are lots of planes out here, not all of which are bedding planes. 2 Map Symbols (not all of these will be useful today) Strike and dip of bedding (long line is oriented on map parallel to strike and short line is oriented in dip direction with dip value written at the end) Anticline (long line follows the crest—line of zero dip—of the anticline) Syncline (long line follows the trough—line of zero dip—of the syncline) Reverse fault (long line follows the trace of the fault on the map; teeth go on the hanging wall) Normal fault (long line follows the trace of the fault on the map; bar and ball go on the hanging wall) Strike-slip fault (long line follows the trace of the fault on the map; arrows indicate sense of motion 3 4