DEPTH IN KARATE

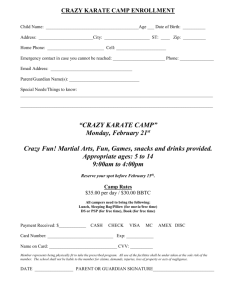

advertisement

E RIC K A TZ Depth In Karate April;1979 When Gichin Funakoshi, one of the early masters and founders of karate spoke of karate, he used the term "karate-do,” which translates as “the way of karate." In other words, to fully understand this art, is not enough to treat it as a separate thing: to think in terms of "now it is time to do karate." To the true karate master, karate is a way of life. To become a master of karate, as becoming a master of anything, requires years of dedication and hard work. We practice the basic movements until they become instinctive, we perform exercises so that our body is strong enough to perform; but we must, also develop a feel for the art, or an understanding of the essence of the art. But where do we look for this essence? There are many types of art. In music, the tangible result of what the artist does is the sounds. In painting, the result is the picture. But in karate, the result of the art is the movements themselves. How do we perfect the art of movement? The masters of karate tell us this is done through kata. We can practice sparring until we win all of our matches. We can practice basic movements until their effectiveness is beyond question. But this will not teach us the true essence of the art of karate. We will not gain a feel for the unifying thing that ties all of karate together. A snap kick will be a snap kick; an inward block will be an inward block. There will be no relation between the various movements. We can learn more and more individual self-defense techniques, hut each new technique will not add to the effectiveness of the previously learned techniques. We can memorize more and more, but not become more proficient in what we already have learned, We can increase our breadth of knowledge, while what we really need to do is increase the depth. We need to learn how to move to make each movement more effective. We need to reach the point where our movements are instinctive. We don't want to be like the fabled woman who studied judo for years in the hope she would be attacked so she could use her knowledge. Finally, one day she was attacked, and she defended herself by striking her assailant with her purse. Her training had not become a part of her; it lacked depth. She divided her time into “judo time" and "regular time." She lacked the feel and understanding for the art. The concept of depth of understanding appears everywhere. In any field, first we memorize, then we learn, then we understand, and finally we feel. All of the individual things we learned flow together. My own experience with this "one-ness" of knowledge lies in science and mathematics, When I see a mathematical formula, I don't see it as a sequence of symbols to be memorized, and plugged into when a specific problem arises, I try to understand what the formula is actually saying. I tie it in with related pieces of knowledge, so the formula is assimilated, not memorized. In college, I once tutored a friend in linear algebra, although I had never seen that particular branch of math before. I could pick it up almost immediately as I read Eric Katz Depth In Karate through his textbook, because I already had an underlying understanding and feel for mathematics, not just a list of memorized formulas and techniques. An analogy is also made in music. In order to become a goad musician, a great deal of practice is required to memorize the various selections. However, in order to become a great musician, practice is not enough. A deeper feel, or understanding, of all music must be reached. The same is true of karate; each movement we learn becomes a part of our overall pool of knowledge, so that it adds depth to all of the other moves. How do we increase the depth of our understanding of karate? How do we unify all of the individual pieces? The karate masters tell us this is done through kata; kata is the essence of karate. By doing kata, we learn to understand karate. By perfecting our katas, we add depth to all of our karate. This idea is extended in the teachings of tai chi, the Chinese art in which one practices movement to understand relationship with nature. This is summarized in the yin/yang symbol, The yin and the yang represent opposites which must work in harmony, The symbol represents a flow of movement within a circle, of similar yet contrasting energies moving together and blending together. This concept finds many applications in karate: aggressiveness and passiveness; attack and defense; expending of power and relaxing. These extremes must he brought into proper balance to he effective. The chi also studies the flow of energy from the body. The energy is said to originate from the center of the body, or chi. The student of tai chi is taught that his energy must not be wasted, that it must 'be recaptured after it is used. As we perform a movement the energy flows outward into our limbs; but at the conclusion of the movement we must recapture this energy. One way we do this is by recoiling our movements. If we think of our leg as a coiled spring, we release this energy when we perform a kick. At t he conclusion of the kick we recoil our leg to recapture this energy so that we are ready for our next movement. We extend this principle to all our movements, so that each movement is executed with maximum energy for the maximum effectiveness. But at the conclusion of the movement, we have re-centered our energy so that our next movement can also be executed with maximum energy, There are other methods of adding depth to our understanding of karate. We can single out a basic movement and develop it. We can work on cleanliness of movement, focus, and accuracy. For example, by properly integrating the entire body into the execution of a wellfocused punch, we have increased our understanding of focus. We can apply this to our other hand strikes, then to blocks, and then to blocks, and then to transitions. Likewise, if we develop the self-discipline to execute a kick that reaches its target quickly and accurately, this will carry over into the speed and precision of all of our hand strikes. The reflexes we develop in freestyle add to our effectiveness in self-defense. The forms we develop during kata add to the depth of our understanding of balance, timing, coordination, and cleanliness of moves. There are many ways we pursue this depth. We watch others move, and we study ourselves in so that we can emulate those who move the way we want to move. We repeat the moves over and over, getting closer and closer to the goals, The goals are often subtle, and cannot be verbalized precisely, “The body must move in harmony.” The move "has to look right.” “The timing has to be there.” Just to understand what it is we are after requires a degree of depth found only after the higher belts have been Eric Katz Depth In Karate earned. We can see an example of this progression of development by recalling our lower belts. When we were first beginning to study the art, our instructors made corrections to our movements, often repeating the same corrections lesson after lesson. At this stage we failed to comprehend the subtleties or the importance of what he was trying to teach us. It was only after we attained sufficient depth that we began to understand what our instructor was trying to tell us. Finally, when we reached this level, we could incorporate these refinements into our own moves, adding still further to our depth. It was not the instructor who changed, who suddenly became a more effective teacher – we became a more effective student. How many times have we seen a purple or blue belt race through a technique, moving as fast as he can? He equates speed with proficiency. His instructor will tell him to slow down the technique, to explode the movement here, to pause there, use power in this section, move lightly in that section, Yet, at the very next lesson the student will race through the technique, moving in the way characteristic to that student, At this point in his studies he lacks the depth to understand why he must move in this new way. It sometimes happens that a student feels like he is not learning, or not progressing and he requests a new instructor. Usually, at our dojo, this request will be granted. For the first few lessons, the student's interest increases as he is exposed to the new instructor. But during this same time, the instructor is observing the weak areas of the student. It is not long before the student begins to hear the same old corrections from his new instructor, It is only when he achieves sufficient depth to understand and begin to incorporate his instructor's corrections that the student will resume progress in the art. Thus we begin to see the importance of depth. Not only must we achieve it to become effective karatekas, but also we must develop it simply to make any progress in the art at all. Ultimately, however, the attainment of depth requires work. We must understand what it is we are after, then we must develop the coordination of our entire body to perform the move. The final stage is the most difficult one. We must move in the desired way consistently. Every time the move is done, it must be done as it should he done. Whether we move at full speed or simply walk through the move, whether we are just warming up or are tired at the end of a long lesson, the move must be done correctly, every time. It is only when the correctness of the move becomes a part of us that we have reached the level of depth that we call Shodan.