11(a)-(c) - BOSTON GROUP

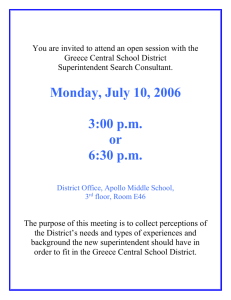

advertisement