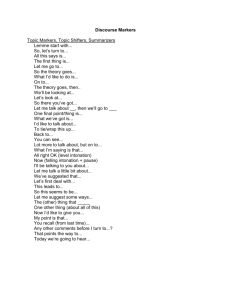

phenomena discourse

advertisement