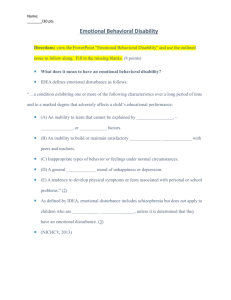

Word - Arts - University of Waterloo

advertisement