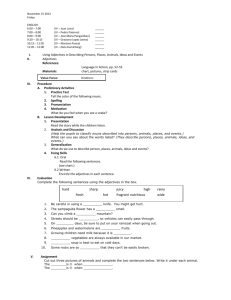

Paper on functional projections of the noun

advertisement

FUNCTIONAL PROJECTIONS OF THE NOUN*

Andrew Radford

University of Essex

This paper is concerned with the syntax of nominal and pronominal

constituents of various kinds, focusing particularly on the structure of

nominals such as those below which contain (italicised) adnominal 'modifiers'

of various kinds (Determiners, Quantifiers and Adjectives):

(1)(a)

(b)

all the good students of Linguistics

few good students of Linguistics

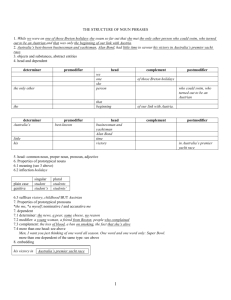

Within the classic NP analysis of such nominals (as outlined e.g. in Radford

1988), prenominal Adjectives are analysed as N-bar adjuncts, prenominal

Quantifiers like few/many and Determiners like the are analysed as NPspecifiers, and predeterminer Quantifiers like all/both are analysed as NPadjuncts. Thus, (1)(a) and (b) would be assigned the respective structures

indicated in (2)(a) and (b) below:

(2)(a)

(b)

[NP [QP all] [NP [D the] [N' [AP good] [N' students of Linguistics]]]]

[NP [QP few] [N' [AP good] [N' students of Linguistics]]]

The classic NP analysis has the virtue of providing a fairly

straightforward account of a number of aspects of the syntax of nominals. For

example, if universal Quantifiers like all/both are NP-adjuncts, then since

adjuncts are often positioned to the left or right of the expressions they

modify (cf. Radford 1988: 255-6), this would provide a natural account of the

dual prenominal and postnominal position of the italicised universal

Quantifiers in structures such as:

(3)(a)

(b)

both you and me/you and me both

tot textul/textul tot (Romanian)

all text+the/text+the all (= 'all the text')

Similarly, if both Determiners and prenominal Quantifiers such as few/many

function as NP-specifiers, and if we assume that Maximal Projections are

binary-branching, we correctly predict that they are generally mutually

exclusive: a structure such as *few the remaining hostages would be ill-formed

because the overall NP would be a ternary-branching structure comprising the

QP few, the D the and the N-bar remaining hostages. What remains to be

accounted for under such an analysis is why Quantifiers like many/few can be

positioned after Determiners, e.g. in nominals such as the few remaining

hostages. One possible solution might be to posit that many/few in such uses

function as Adjectives: this would account for the fact that they can precede

or follow other Adjectives, and can be used predicatively: cf.

______________________________________________________________________________

*This is the text of a paper presented at a workshop on functional categories

at a meeting of the Linguistics Association of Great Britain in York, 16

September 1991. It was published under the same title in Radford, A. (ed)

Functional Categories: Their Nature and Acquisition, Dept. Language and

Linguistics Occasional Papers 33: 1-25 (1992), University of Essex.

(4)(a)

(b)

the remaining few hostages/the few remaining hostages

His friends are few; his enemies are many

It might also account for the fact that few triggers 'Auxiliary Inversion'

when used as a Quantifier, but not when used as a (seeming) Adjective: cf.

(5)(a)

(b)

Few of the remaining hostages will they release unharmed

*The few remaining hostages will they release unharmed

As Adjectives, few/many would serve as adjuncts to N-bar, and hence follow

Determiners like the.

If we assume that prenominal Adjectives are adjuncts to N-bar, we provide a

straightforward account of the fact that Adjectives follow Determiners (cf.

'the good students'/*'good the students'). More specifically, if we assume

that Adjectives are potentially iterable adjuncts to N-bar, as in (6) below:

(6)

N' = AP*

N'

we then predict that Adjectives can be recursively stacked either linearly or

hierarchically: linearly stacked Adjectives would have an appositive

interpretation, and hierarchically stacked Adjectives would have a restrictive

interpretation. This would enable us to provide a structural account of the

ambiguity of a string such my first(,) disastrous marriage, along the lines

suggested in Radford 1988: 222. The two interpretations would correspond to

the two structures in (7) below, with the Adjectives hierarchically stacked in

(7)(a), and linearly stacked in (7)(b):

(7)(a)

(b)

[NP [D my] [N' [AP first] [N' [AP disastrous] [N' marriage]]]]

[NP [D my] [N' [AP first], [AP disastrous] [N' marriage]]]

If we posit that prenominal APs have scope over any nominal they c-command,

it follows that disastrous in both structures will have scope over the N-bar

marriage, but that the two structures will differ in that first has scope over

the N-bar disastrous marriage in (7)(a) (implying that I had other disastrous

marriages), but has scope only over the N-bar marriage in (7)(b). Of course,

the structural differences here correlate with phonological differences

(relating to stress pattern and intonation contours), and these are reflected

in the orthography by the presence or absence of a comma between the stacked

Adjectives.

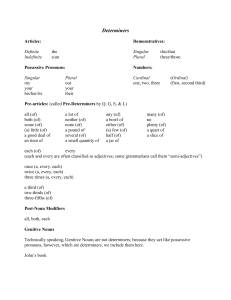

Interesting though the classic NP analysis is, there are some aspects of it

which seem potentially problematic. One of these is the treatment of

prenominal Determiners. In early versions of the 'classic' analysis, these

were treated as unprojectable (i.e. zero-level categories which had no phrasal

projections into single-bar or double-bar categories). However, such an

analysis is objectionable on both theoretical and empirical grounds. From a

theoretical point of view, if D is unprojectable, then it is anomalous in that

all other categories have phrasal projections (including other functional

categories such as C and I, which have phrasal projections into CP and IP

within the framework of Chomsky's 1986 Barriers monograph). Moreover, if we

assume that Determiners are generated by a PS rule of the form NP = D N',

there will be an obvious violation of the constraint proposed by Stowell

(1981, p. 70) to the effect that 'Every non-head term in the expansion of a

rule must itself be a maximal projection of some category.' Thus, theoretical

considerations would lead us to conclude that if Determiners are specifiers of

N-bar, they must have the status of DP (Determiner Phrase) constituents.

Empirical considerations lead us to the same conclusion, since we find that

Determiners can be premodified by a variety of expressions which could

arguably be analysed as their specifiers: e.g. the italicised constituents in

the bracketed NPs below might be argued to function as the specifiers of the

bold-printed Determiners:

(8)(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

He made [precisely this point]

Diamonds sell at [several times the price of rubies]

He is [quite the best student] we've ever had

There is [many a slip] twixt cup and lip

(e)

(f)

(g)

(h)

(g)

[What a fool] I was!

I have never witnessed [so tragic an accident]

He made [rather a mess]

[Not a drop] did I spill

Tu veux [encore une pomme]? (French)

You want [again an apple]? (= Do you want another apple?)

N-a venit [nici o persoana] (Romanian)

Not-has come [not a person] (= 'Not a single person came')

(h)

If the italicised constituents do indeed function as the specifiers of the

bold-printed Determiners, then it seems clear that Determiners must have

phrasal projections (from D into DP), just like other categories. Within the

spirit of the NP framework, we might therefore propose (cf. Radford 1988: 263)

that Determiner expressions which function as NP-specifiers project into DP,

so that nominals such as [several times the price of rubies] or [so tragic an

accident] would have the structure (9) below:

(9)(a)

NP

(b)

DP

NP

several

times

NP

N'

D'

D

N

price

DP

PP

of rubies

AP

so tragic

the

N'

D'

D

N

accident

an

If we analyse s-phrases (i.e. so/such phrases) as specifiers of D, we can

provide a straightforward account of paradigms such as the following:

(10)(a)

(b)

(c)

I have never before witnessed [such a quite so tragic accident]

*I have never before witnessed [such quite so tragic an accident]

*I have never before witnessed [quite so tragic such an accident]

If we assume (as earlier) that maximal projections are binary-branching and

that an s-phrase can serve as the specifier of the Determiner a, then it

follows that only one of the two s-phrases can occupy the predeterminer DPspecifier position in structures like (10) - in precisely the same way as only

only wh-phrase can serve as the specifier of C in English.

So, it would seem that a fairly trivial modification of the traditional NP

analysis (viz. treating Determiner expressions as phrasal DP constituents

which allow specifiers of their own) will accommodate the fact that

Determiners can be 'premodified' by a range of predeterminer expressions. Such

an analysis also has obvious theoretical advantages, in that it is no longer

necessary to posit that Determiners are unprojectable heads: under the revised

analysis, just as N projects into NP, V into VP, I into IP, and C into CP, so

too D projects into a DP constituent which functions as the specifier of NP.

However, there are both theoretical and empirical problems posed by analysing

DPs as specifiers of NPs. From a theoretical point of view, the essential

problem is that Determiners are anomalous in that they have no complements of

their own - as we see from the fact that D is the sole constituent of D-bar in

structures like (9). Thus, DPs fail to conform to the generalised X-bar schema

(11) below:

(11)

[XP specifier [X' [X head] complement/s]]

What (11) says is that any head category X can combine with a following

complement to form an X-bar constituent (which in turn can be combined with a

preceding specifier to form an XP). Under the analysis of DPs as NPspecifiers, Determiners are anomalous in that no Determiner ever permits a

following complement of any kind - unlike other functional categories (e.g. C

takes an IP complement, and I takes a VP complement).

One way in which we might try and overcome this problem would be to suggest

that the 'defectiveness' of Determiners in not permitting complements is not

restricted to Determiners alone, and that other categories share this

property. For example, it is suggested by Jackendoff (1977: 78) that Adverbs

are similarly heads which permit specifiers but not complements, and in this

respect contrast with Adjectives, which permit both complements and

specifiers: cf. e.g.

(12)(a)

(b)

(c)

She smiled, [very confident of success]

She smiled [very confidently]

*She smiled [very confidently of success]

Thus, whereas an Adjective like confident permits both a following complement

like of success and a preceding specifier like very, the corresponding Adverb

confidently permits a preceding specifier, but no following complement. We

might therefore suggest that Determiners are no more anomalous than Adverbs in

respect of not permitting complements.

However, the generalisation that Adverbs never permit complements is

falsified by examples such as the following:

(13)(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

(e)

You must make up your mind independently of me

Are you going to do it differently from me?

She dresses similarly to me

She goes swimming more than me

I'll let you know immediately she arrives

Thus, it is not a general structural property of Adverbial Phrases that they

do not license complements, but rather a lexical property of individual

Adverbs. By contrast, under the analysis of DPs as NP-specifiers, we are

forced to posit either that it is a general structural property of all DPs

that they never permit a complement, or that it is an idiosyncratic#lexical

property of every individual Determiner in English that (coincidentally) none

of them permits a complement. Now, it seems unlikely to be either a general

structural property of DPs, or an accidental lexical property of (all)

Determiners that they never permit complements, since we do find other uses of

certain Determiners in which they permit complements (such as those boldprinted below):

(14)(a)

(b)

Her behaviour was that of a four-year-old

Those of you who wish to do so may leave

Thus, if DPs are to be analysed as NP-specifiers, we have no principled

explanation of the fact that only when used prenominally do Determiners not

allow complements. Given that the essential motivation of X-bar syntax is to

establish cross-categorial symmetry in the ways in which heads project into

phrases, the resulting asymmetry is clearly problematic.

Moreover, the specifier analysis is also questionable on the grounds of its

putative descriptive inadequacy, in that the constituent structure which it

assigns to DPs is counterintuitive. Thus, it seems counterintuitive to claim

that in structures such as (10) above, the strings several times the and so

tragic an are constituents. On the contrary, it seems more plausible at an

intuitive level to claim that Determiners are closely linked to (and form a

constituent with) the expressions which follow them, so that the strings the

price of rubies and an accident are constituents of some kind. This kind of

'close relation' between Determiners and the expressions following them seems

plausible on phonological grounds, in that the phonological form of a

Determiner is often dictated by the initial segment of the first word of the

postdeterminer string: for example, a takes the form an and the is homophonous

with thee when the initial segment of the postdeterminer expression is a

vowel. In Italian, the masculine singular definite article takes the form l'

before a vowel (e.g. l'albero 'the tree'), lo before an s+consonant cluster

(e.g. lo specchio 'the mirror'), and il before other consonants groups (e.g.

il mondo 'the world'). In many languages, this 'close relation' between

Determiners and postdeterminer expressions leads to cliticisation of

Determiners to the initial word of the postdeterminer expression: e.g. in

Yorkshire dialects of English, the definite article procliticises to the

following word (cf. 'On Ilkley Moor bar t'hat'), while in Romanian the

definite article encliticises to the following word (cf. 'textul', literally

'text+the', i.e. 'the text').

Moreover, coordination evidence strongly suggests that in sequences of the

form Predeterminer+Determiner+Nominal, the Determiner forms a constituent

together with the following nominal, rather than with the preceding

predeterminer. Thus, in the following examples, the pattern of coordination in

the (a) example is far more natural than that in the (b) examples:

(15)(a)

Diamonds sell at [several times the price of rubies or the price

of amethysts]

(b)

*Diamonds sell at [four times the or five times the price of

rubies]

(16)(a)

(b)

I have never met [so outstanding an academic or a politician]

*I have never met [so outstanding an or so witty an academic]

These examples show that a Determiner+postdeterminer string can be coordinated

with another such string (as in the (a) examples), so suggesting that the two

form a constituent of some kind: however, they also show that a

predeterminer+Determiner sequence cannot be coordinated in this way, so

suggesting that it is a nonconstituent sequence. Thus, coordination evidence

seems to falsify the analysis in (8) above, since (8) specifically claims that

predeterminer+Determiner strings are constituents.

What all of this seems to suggest is that the immediate phrasal projection

of a prenominal Determiner must include the expression which follows the

Determiner, rather than that which precedes it. But how can this be? A natural

answer would be to take the postdeterminer expression to be the complement of

the Determiner, and the predeterminer expression (as before) to be its

specifier. This would mean (e.g.) that strings such as several times the price

of rubies and so tragic an accident would no longer have the respective

structures in (10)(a) and (b) above, but rather those in (17)(a) and (b)

below:

(17)(a)

DP

(b)

NP

several

times

D'

D

the

DP

AP

NP

price of gold

so tragic

D'

D

an

NP

accident

We might refer to the analysis in (17) as the DP analysis (since it posits

that determinate nominals are DP constituents), and that in (10) as the NP

analysis (since it posits that determinate nominals are NP constituents). It

should be clear that the DP analysis offers both theoretical and descriptive

advantages over the earlier NP analysis. From a theoretical point of view, the

obvious advantage is that we now no longer need to posit that prenominal

Determiners are anomalous in respect of not permitting a complement, since the

postdeterminer nominal is analysed as the complement of the Determiner (e.g.

price of gold is the complement of a in (17)(a), and accident is the

complement of an in (17)(b)). From a descriptive point of view, the most

immediate advantage is that we are now able to handle the coordination data in

(15) and (16), since the DP analysis correctly predicts that a

Determiner+nominal structure forms a D-bar constituent, and can therefore be

coordinated with another similar D-bar string.

One of the ways in which the DP analysis differs from the NP analysis is

that the DP analysis sees the relation between a Determiner and a following

nominal as a head-complement relation, whereas the NP analysis sees it as a

specifier-head relation. Some empirical evidence in support of the DP analysis

would seem to come from agreement facts in sentences such as the following:

(18)

[This/*These parliament] has/have decided to revoke the act

The bracketed nominal this parliament would standardly be analysed as the

specifier of the Auxiliary have, so that there is a specifier-head relation

between the two. The agreement relation between the subject specifier and the

Auxiliary head may either be 'syntactic' (so that the singular form has may be

used because this parliament is a morphosyntactically singular nominal), or

'semantic' (so that the plural form have may be used because the subject this

parliament denotes a set of individuals). Now, if the relation between a

Determiner and a following nominal were similarly a specifier-head relation,

then we should expect to find the same dual pattern of 'syntactic/semantic'

agreement holding between the Determiner this and the Noun parliament. But in

fact this is not the case at all: on the contrary, strict syntactic agreement

is required here, suggesting that the relation between a Determiner and a

following Noun may be structurally distinct from the specifier-head relation

which holds between a subject and a Verb. Of course, under the DP analysis,

the relationship is indeed distinct, since it is a head-head relation (between

a governing matrix head and a governed complement head).

The assumption that Determiners are the heads of their containing nominals

has interesting implications for the structure of Noun Phrases. Under the

classic NP analysis, D was the specifier of NP; but if D is now the head of a

separate phrasal projection (DP) and so lies 'outside' the N-system, the

obvious question to ask is whether N now licenses a specifier of its own or

not. The answer given to this question in Fukui 1986 is 'No'. Fukui argues

that there is a crucial asymmetry between lexical and functional categories,

in that any lexical category L can be combined with a following complement to

form an L-bar constituent, which in turn can be recursively combined with

modifiers (adjuncts) of various kinds to form successively larger and larger

L-bar constituents - so that the maximal projection of any lexical head is a

single-bar constituent. By contrast (Fukui argues) any functional head F will

project into F-bar by the addition of a complement, into further F-bar

constituents by the addition of modifiers (adjuncts), but will also project

into F-double-bar (= FP) by the addition of a specifier phrase of an

appropriate kind. Thus, for Fukui, the crucial difference between lexical and

functional categories is that the maximal projection of a lexical head is a

single-bar constituent, whereas the maximal projection of a functional head is

a double-bar constituent.

Given that the essential motivation for the DP analysis is to eliminate any

asymmetry between lexical and functional categories with respect to the ways

in which they are projected into the syntax, Fukui's analysis seems a

retrograde step from a theoretical point of view (in that it creates a new

asymmetry between the two types of head, relating to whether they have a

double-bar projection or not). In Radford 1991, I argue against Fukui's

asymmetrical analysis and in favour of an alternative symmetrical analysis in

which both N and D constituents can be projected from a single-bar to a

double-bar constituent by the addition of a phrasal specifier. More

specifically, I argue that the italicised nominal in structures such as (19)

below functions as the specifier of the capitalised Noun head:

(19)(a)

(b)

(c)

ministry of defence INSTRUCTIONS to all employees

government CRITICISM of the press

Labour Party POLICY on defence

(d)

military police INVOLVEMENT in torture of prisoners

(e)

university management ALLEGATIONS of a concerted student

campaign of disruption

(f)

European Community DEMANDS for monetary union

(g)

student assessment of lectures

(h)

Department of the Environment plans for a new motorway

Under the analysis proposed in Radford 1991, the nominal expressions in (19)

would be NPs of the schematic form [specifier+HEAD+complement], so that (e.g.)

(19)(a) would have the simplified superficial syntactic/thematic structure

(20) below:

(20)

NP

NP

<------AGENT-------

Ministry of

Defence

N'

N -----GOAL----> PP

instructions

to all employees

A structure such as (20) conforms to the canonical pattern of theta role

assignment in English (with the AGENT argument being externalised and the GOAL

argument internalised), and likewise conforms to canonical configurational

properties, so that e.g. the HEAD/COMPLEMENT PARAMETER is properly set in

that the head Noun instructions precedes its PP complement to all employees.

What makes it all the more plausible to analyse the italicised expression

in nominals such as (19) as the specifier (and external AGENT argument) of its

containing nominal is the fact that (like other specifiers) it can serve as

the controller of PRO, e.g. in structures such as the following:

(21)(a)

Ministry of Defence reluctance PRO to admit mistakes

(b)

opposition attempts PRO to secure themselves a place on the

committee

(c)

government unwillingness PRO to compromise with the opposition

(d)

Department of the Environment plans PRO to commission a new

railroad linking London to Dover

Thus, the assumption that nominals such as (19) are Noun Phrases with an

internal constituent structure along the lines of (20) above would seem to

have a certain amount of initial plausibility.

An interesting variant of the pattern found in (19) above is that found in

nominals like those in (22) below:

(22)(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

(e)

(f)

(g)

(h)

(i)

(j)

enemy heavy artillery losses

Labour Party defence policy

government income tax reforms

opposition corruption allegations

European Community sheep meat subsidies

Ministry of Defence satellite intelligence procurement

student lecture assessment

cabinet higher education expenditure cuts

press censorship claims

Buckingham Palace reporting restrictions

It seems plausible to suppose that the italicised nominal serves the thematic

role of AGENT, whereas the bold-printed nominal serves that of PATIENT. Since

canonical AGENTS are specifiers and canonical PATIENTS are complements, we

might suggest that an NP such as (22)(a) has the structure (23) below:

(23)

NP

NP

enemy

<--------AGENT-------NP

N'

<---PATIENT-- N

heavy artillery

losses

What makes it all the more plausible to consider the first nominal to be an

AGENT specifier and the second to be a PATIENT complement is the fact that the

former is often paraphraseable by a by-phrase, and the latter by an of-phrase:

(24)(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

(e)

(f)

(g)

loss of heavy artillery by the enemy

reforms of income tax by the government

allegations of corruption by the opposition

subsidies of sheep meat by the European Community

procurement of satellite intelligence by the Ministry of Defence

assessment of lectures by students

claims of censorship by the press

A further piece of evidence which suggests that it is plausible to treat

nominals such as those in (20) as structures of the form

[specifier+complement+head] relates to the fact that the putative specifier

and complement cannot be substituted for each other (i.e. cannot have their

relative ordering changed), as we see from the ungrammaticality of examples

such as the following:

(25)(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

(e)

(f)

(g)

(h)

*income tax government reforms

*heavy artillery enemy losses

*corruption opposition allegations

*sheep meat European Community subsidies

*satellite intelligence Ministry of Defence procurement

*lecture student assessment

*censorship press claims

*reporting Buckingham Palace restrictions

This suggests that the two occupy different structural positions (precisely as

is claimed in (23) above).

If the analysis outlined here is along the right lines, then it follows

that (contrary to the claim made by Fukui 1986) there are no projectional

asymmetries between lexical and functional categories: both can project from a

single-bar into a double-bar constituent by the addition of a preceding

specifier phrase. The specifier of an NP is a 'subject' NP which is thetamarked by its sister N-bar, and which can serve as the controller for a PRO

subject in a complement clause. This analysis ties up in interesting ways with

the recent suggestion in a number of works that clausal subjects originate

within VP as the specifier of the V-bar which assigns a theta role to them

(cf. e.g. Hoekstra 1984, Sportiche 1988, Kuroda 1987, Fassi Fehri 1988 and

many others). We can then arrive at a unitary analysis by positing that just

as the 'subject' of a clause originates as the specifier of VP, so too the

'subject' of a nominal originates as the specifier of NP (For some thoughts on

the conditions under which an NP is licensed to occur as the specifier of

another NP, see Radford 1991).

Our earlier observation (made in relation to examples such as (8) above)

that Determiners license specifiers of their own suggests an interesting

analysis of structures involving so-called 'genitive 's'. Consider, for

example, how we might deal with a possessive 's structure such as that in (26)

below:

(26)

the government's tax reforms

Following a suggestion attributed by Abney (1987, p. 79) to Richard Larson, we

might suggest that possessive 's (in this kind of use) be analysed as a head

Determiner which licenses an NP complement and a DP specifier. Given these

(and earlier) assumptions, (26) would have the skeletal structure indicated in

(27) below:

(27)

[DP [DP the government] [D' [D 's] [NP tax reforms]]]

There are a number of empirical arguments in support of analysing possessive

's as a head Determiner in English. For example, like demonstrative

Determiners in English, possessive 's can be used both prenominally and

pronominally: cf.

(28)(a)

(b)

These houses are bigger that those

Mary's house is bigger than John's

Moreover, there are strong distributional parallels between 's and the

definite determiner the: they are the only two Determiner constituents which

can precede the postdeterminer Quantifier every: cf.

(29)(a)

(b)

Congressmen pander to the every whim of the president

Congressmen pander to the president's every whim

In addition, both the and possessive nominals can be preceded by the same

range of predeterminer Quantifiers, as we can illustrate in terms of (30)

below:

(30)(a)

(b)

all/both the problems

all/both John's problems

And significantly, possessive 's and other Determiners are mutually

exclusive, as we see from examples such as the following:

(31)

*the president's this/that/a/the friend

(Nominals like (31) do not seem to be semantically ill-formed in any way,

since they have coherent paraphrases - cf. 'a/the friend of the president',

'this/that friend of the president's'.) Given that Determiners do not license

DP complements, what this suggests is that possessive 's belongs to the same

category as items like this/that/a/the - i.e. to the category of third

person Determiners. Thus, it seems reasonable to posit that possessive 's is

a Determiner which carries much the same morphosyntactic and semantic

properties as the, but differs from the in that it licenses (indeed,

requires) a possessor DP as its specifier (perhaps because 's is a suffix, or

perhaps because it must obligatorily discharge case onto an overt specifier,

in much the same way as a finite INFL constituent like will in English

obligatorily requires an overt specifier to discharge nominative case onto),

and in that it can be used pronominally as well as prenominally.

Interestingly, 's generally requires a nominal rather than pronominal

specifier (so we have 'what party's policy?', but not *'what's policy?').

English possessive 's structures find an interesting counterpart in

structures such as the following in Dutch (from Stuurman 1991):

(32)

Jan z'n vrienden

Jan his friends (= 'Jan's friends')

It seems reasonable to suppose that the possessive pronoun z'n here is the

head of the overall DP, and that Jan is its specifier (though this is not the

analysis adopted by Stuurman) , so that a string like (32) has the structure

(33) below (where SPEC = specifier)

(33)

[DP [SPEC Jan] [D' [D z'n] [NP vrienden]]]

We might then see the structural relationship between the head and specifier

of a possessive DP in (33) as very much akin to the relationship between INFL

and its specifier: thus, the head agrees with the specifier (Jan is third

person singular, so the head pronoun z'n is also third person singular), while

the specifier is case-marked by the head: similarly, INFL agrees with (and

assigns case to) its specifier.

Of course, a possessive pronoun such as z'n does not require an overt

specifier, and hence can occur in nominals such as z'n vrienden 'his friends'.

One way of analysing such nominals would be to suppose that the specifier

(i.e. the possessor phrase) is null in such cases, and that the null specifier

is licensed by the rich system of specifier-agreement properties carried by

possessive pronouns in Dutch (in much the same way as null subjects are

licensed by the rich system of specifier-agreement inflections carried by

finite Verbs in many languages). We might then extend this analysis to

possessive pronouns in English, so that in an expression such as her car, her

is a head Determiner which licenses a null specifier: this specifier (viz. the

possessor) is unamiguously identifiable as a third person feminine singular

expression by virtue of the rich specifier-agreement properties carried by

possessive pronouns like her in English.

The parallel drawn here between the D system and the I system raises an

interesting question, in the light of the observation made in Chomsky's (1989)

Economy of Derivation paper that INFL in languages with rich inflection

systems carries both subject-agreement (= AGR-S) and object agreement (= AGRO) properties. If we reinterpret AGR-S to mean 'specifier-agreement' (i.e.

agreement between a head and its specifier), then we might say that pronouns

such as her in English and z'n in Dutch agree with their specifiers (whether

overt or covert), and so carry AGR-S properties. But this would lead us to

expect to find languages in which possessive Determiners exhibit AGR-O

properties as well as AGR-S properties - i.e. languages in which possessive

pronouns agree with their complements as well as their specifiers.

It seems reasonable to suppose that French is such a language, as we can

see by considering the morphosyntax of the italicised possessive pronouns in

(34) below:

(34)(a)

(c)

sa copine

his/her (girl-) friend

ses copines

his/her (girl-) friends

(b)

(d)

son copain

his/her (boy-) friend

ses copains

his/her (boy-) friends

We might argue that possessive pronouns in French inflect for agreement both

with their 'understood' specifier (more specifically, with the person/number

properties of the specifier), and with their complement (more specifically,

with the number/gender properties of their complement). The initial consonant

of the pronoun (m+/t+/s+/n+/v+/l+) generally seems to carry the AGR-S features

(identifying the person and number of the possessor), while the remainder of

the pronoun carries AGR-O features (identifying the number and gender of the

complement). Thus, in a form such as sa, s+ carries the AGR-S properties and

identifies the possessor as third person singular (his/her/its), whereas +a

carries the AGR-O properties and identifies the possessee as feminine

singular. In contrast to French, possessive pronouns in English mark only AGRS properties, and hence do not carry complement agreement properties: this may

well be related to the fact that English is a language in which Verbs agree

with their subjects, but not with their complements.

Given the assumptions we are making here, the range of possessive

structures found in Dutch, English and French would be as indicated in

schematic form in (35) below (where e denotes an empty/null specifier, and

dotted lines represent a morphophonologically realised agreement relation):

(35)

DP

SPECIFIER

D'

D

Jan/e .......

John

e ..........

e ..........

z'n

's

his

sa ........

COMPLEMENT

vrienden

friends

friends

copine

We might suppose that there are three main parameters along which possessive

heads differ in the three languages. One is in respect of whether they agree

with their specifier and/or complement - these agreement relations being

marked by dotted lines in (35). A second is in respect of whether or not

possessive heads license an overt and/or covert (possessor) specifier. A third

is whether or not a given possessive head licenses an overt and/or null

complement (e.g. my in English licenses an overt NP complement such as picture

of you, but mine does not - cf. *mine picture of you). We might pursue a

variety of explanations for these properties: e.g. the fact that 's does not

license a null specifier might be because of its lack of any overtly marked

AGR properties, and/or because it is a suffix which needs to be attached to

an appropriate host, and/or because it must obligatorily discharge case

features onto an overt nominal specifier. Equally, alternative analyses might

be envisaged (e.g. we might argue that possessive heads with no overt

specifier absorb the case they assign to their specifier and so have an

incorporated specifier which is not projected into the syntax; we might follow

Abney 1987 in taking possessive 's to be a head case assigner, or Lyons 1991

in taking it to be a genitive case ending).

Our brief discussion of possessive pronouns raises the more general

question of how we deal with the morphosyntax of pronouns (and especially

personal pronouns) within the DP framework. Since pronouns are words, the most

principled account which we can offer of the syntax of such items is that

(like all other words) they must therefore belong to word-level categories:

this excludes in principle any analysis of pronouns as phrasal proforms (e.g.

it excludes the traditional analysis outlined in Radford 1981 under which one

is analysed as an N-bar proform, and he as an NP proform), if

principles of

Universal Grammar forbid the insertion of a word under a phrasal node (viz.

under X-bar or XP). Given these assumptions, then it follows that each

different type of nominal head might be expected to have a pronominal

counterpart. Thus, in an analysis which posits that determinate nominals are

double-headed constituents (in the sense that they comprise an N which

projects into an NP which serves as the complement of a D which projects into

a DP), we might expect to find two rather different types of pronominal

constituent - viz. pronominal N and pronominal D constituents respectively.

For reasons outlined in detail in Radford 1990, we might argue that the

pronoun one (in expressions like 'a blue one') is an N proform, since it has

all the characteristics of a singular count Noun: for example, it can take the

Noun plural +s inflection, it can be premodified by both an Adjective and a

Determiner, and it can take an of complement, as we see from examples such as

the following:

(36)

Which photos? Those awful ones of you in a bikini?

By contrast, pronouns such as this/that/these/those/mine (in the use

illustrated in (28) above) would seem to be more plausibly analyseable as

pronominal Determiners: this would then account for the fact that (unlike the

pronominal N one) they do not take the Noun plural +s inflection and cannot

normally be premodified by Adjectives or other Determiners: cf.

(37)

Which photos? *The awful those of you in a bikini

Thus, it seems plausible to conclude that one (in the relevant use) is a

pronominal N, whereas this is a pronominal D.

An obvious question raised by the assumption that there are two different

types of pronoun (pronominal N and pronominal D constituents) is which

category so-called 'personal pronouns' (like I/you/he etc.) belong to. Such

pronouns seem to have none of the characteristics of typical N constituents:

for example, they never take the N plural +s suffix, and are not normally

premodified by Adjectives or Determiners, and do not take an of complement:

cf.

(38)

Which pictures? *Those awful thems of you in a bikini?

In these respects, they seems to behave more like pronominal Determiners: and

indeed, just such an analysis of personal pronouns as pronominal Determiners

was proposed (within the earlier NP framework) by Postal 1966, and taken up

(within the more recent DP framework) by Abney 1987.

One type of argument in support of analysing personal pronouns as

Determiners can be formulated in relation to paradigms such as the following:

(39)

[The/We/You opponents of the poll tax]

government down

are trying to bring the

In a structure such as (39), the would seem to have the status of a prenominal

Determiner, taking as its complement the NP opponents of the poll tax. The

fact that the can be substituted here by we or you would suggest that we/you

likewise function as prenominal Determiners in structures such as (39). More

precisely, we might suggest that we in (39) functions as a first person

Determiner, you as a second person Determiner, and the as a third person

Determiner. If this is so, then the bracketed nominal in (39) above will have

the skeletal structure indicated in (40) below (simplified by omission of Dbar and the constituents of NP):

(40)

DP

D

we/you/the

NP

opponents of the poll tax

Interestingly, in some varieties of English we/you can serve as Determiners

for the pronominal N ones (hence we find the compound pronouns we'uns and

you'uns in Ozark English, as noted in Jacobs and Rosenbaum 1968, p. 98).

One of the predictions made by an analysis such as (40) is that because the

overall structure has the status of DP, its grammatical properties will be

determined not just by properties of the head N of NP (which may percolate up

to the containing DP) but also by the head D of DP. In this connection, it is

interesting to note the following paradigm:

(41)(a)

(b)

(c)

[We opponents of the poll tax]

have committed ourselves/

*yourselves/*themselves to non-payment, haven't we/*you/*they?

[You opponents of the poll tax]

have committed yourselves/

*ourselves/*themselves to non-payment, haven't you/*we/*they?

[The opponents of the poll tax] have committed themselves/

*ourselves/*yourselves to non-payment, haven't they/*we/*you?

Data such as (41)(a) tell us that a (bracketed) DP headed by we functions as a

first person plural expression and hence can only serve as the antecedent of

the first person plural anaphor and can only be tagged by a first person

pronoun; (41)(b) similarly tells us that a DP headed by you is a second person

expression (and so can only serve as the antecedent of a second person anaphor

and be tagged by a second person pronoun); (41)(c) tells us that a DP headed

by the is a third person expression, and so can only serve as the antecedent

of a third person anaphor like themselves and be tagged by a third person

pronoun like they. What all of this suggests is that the person properties of

the overall structure are dictated by properties of the Determiners

we/you/the, and not by properties of the nominal opponents. Thus,

reflexivisation and tag facts like those in (41) provide us with clear

evidence that pronouns are Determiners, and function as the heads of their

containing nominals (so that the overall nominal structure has the status of a

DP constituent).

We might argue that it is not just the person properties of nominals which

are determined by their D-system, but also their case properties, as we see

from examples such as the following (in Standard English):

(42)(a)

(b)

[We/*Us Americans] envy the British

The British envy [us/*we Americans]

From examples such as (42), it is clear that a nominal like we Americans is a

nominative expression which can only occur within the domain of a nominative

case-assigner (i.e. as the subject of a finite clause), whereas an expression

such as us Americans is an objective expression which can only occur within

the domain of an objective case assigner (e.g. where governed by an

immediately preceding transitive Verb like envy). The case of the overall

nominal structure would seem to be determined not by any property of the Noun

Americans (indeed, we might even suggest that Nouns do not carry case in

Modern English), but rather by the prenominal Determiner we/us. Since it is

the case properties of the Determiner which control the case properties of the

containing nominal, it therefore seems natural to take the Determiner to be

the head of the overall nominal expression we/us Americans.

Although it seems plausible to analyse pronouns like we and you as

Determiners, such an analysis might seem far less plausible for (e.g.) a third

person pronoun such as they. In Standard English, they cannot be used as a

prenominal Determiner, as we see from the ungrammaticality of structures such

as *they students. Doesn't this vitiate the D analysis of pronouns like they?

The answer is 'No'. After all, all items have idiosyncratic complementselection properties: just as some Verbs select an overt complement and others

do not, so too we might posit that some Determiners (e.g. we/you/these) select

an overt NP complement, whereas others (e.g. he/she/they) do not. If whether a

given D does or does not select an overt NP complement is a lexical property

of the item concerned, then since much variation between one variety of

English and another is lexical in nature, we might expect to find varieties of

English in which pronouns like they do indeed select an overt NP complement.

It is therefore significant that person pronouns such as they and them can be

used as prenominal Determiners in some varieties of English, as we see from

examples such as the following:

(43)(a)

Tell Cooper to shift they stones there (Devonshire, from Harris

1991, p. 23)

(b)

It was like this in them days, years ago, you see (Somerset, from

Ihalainen 1991, p. 156)

Hence, it is far from implausible to say that items like they/them are

Determiner constituents. What lends cross-linguistic support to the analysis

of personal pronouns as Determiners is the fact that many such pronouns in

other languages can also function as prenominal Determiners (so that e.g.

French les corresponds both to the English Determiner the and to the English

pronoun them, and likewise le corresponds to both 'the' and 'he', and la to

both 'it' and 'she').

The assumption that Nouns and Determiners head separate phrasal projections

provides us with an interesting way of handling the syntax of quantification.

Quantifiers seem to fall into two different distributional classes, as we can

illustrate by contrasting the plural Quantifiers tous 'all' and plusieurs

'several' in French. The (masculine plural) Quantifier tous 'all' in French

can generally premodify only a determinate (masculine plural) nominal (i.e. a

masculine plural nominal premodified by a Determiner), so that we can have

'tous les garc,ons' ('all the boys'), 'tous ces beaux arbres' ('all these

beautiful trees') and 'tous nos ance^tres' ('all our ancestors'), but not

*'tous (beaux) arbres' ('all (beautiful) trees'). By contrast, the

(masculine/feminine plural) Quantifier plusieurs 'several' can modify only an

indeterminate plural nominal (i.e. a plural nominal not premodified by a

Determiner), so that we can have 'plusieurs questions' ('several questions')

and 'plusieurs faux pas' ('several false steps'), but not *'plusieurs ces

arbres' ('several these trees'). How can we account for the fact that tous

quantifies a determinate nominal, whereas plusieurs quantifies an

indeterminate nominal? Within the framework adopted here, it seems natural to

suppose that quantification of a determinate nominal involves quantification

of a DP, whereas quantification of an indeterminate nominal involves

quantification of an NP. But what is the structural relation between the

Quantifier and the quantified expression?

One suggestion (adapted from the traditional NP analysis) might be to treat

Quantifiers as the specifiers of the (DP or NP) nominals they quantify.

However, this assumption would prove problematic in relation to examples such

as:

(44)(a)

(b)

few oppositions attempts to discredit the government

all the president's decisions

Given our earlier arguments that opposition is the specifier of the NP

opposition attempts to discredit the government in (44)(a), and that the

president is the specifier of the DP the president's decisions, it is apparent

that we cannot analyse few as the specifier of NP nor all as the specifier of

DP in the relevant examples, since the nominals concerned already have a

specifier of their own. However, we might alternatively suggest treating

Quantfiers as adjuncts to the nominals they quantify, so that few would be an

NP adjunct, and all a DP adjunct - as in (45) below:

(45)(a) [NP [QP [Q few]] [NP opposition attempts to discredit the government]]

(b) [DP [QP [Q all]] [DP the president's decisions]]

However, the adjunct analysis of Quantifiers poses a number of problems. For

one thing, it wrongly predicts that (since adjunction is a recursive

operation) Quantifiers can be recursively stacked. Moreover, under the adjunct

analysis, Quantifiers are anomalous in respect of not being able to take

complements of any kind (cf. the ungrammaticality of *'few of them the

president's decisions'). But if Quantifiers are neither specifiers of no

adjuncts to the nominals they modify, what is their structural relation to

those nominals?

Given our general assumption that Determiners are the heads of their

containing nominals, a natural answer would be to suppose that Quantifiers too

are the heads of their containing expressions, so that quantified nominals

have the status of Quantifier Phrases headed by their Quantifiers. On this

assumption, nominals such as tous ces arbres 'all these trees' and plusieurs

arbres 'several trees' would have the respective structures (46)(a) and (b)

below:

(46)(a)

(b)

[QP [Q tous] [DP [D ces] [NP [N arbres]]]]

[QP [Q plusieurs] [NP [N arbres]]]

Quantifiers would no longer be anomalous categories which never select

complements, since the complement of a prenominal Quantifier would be the

nominal which it quantifies. We could then say that both quantified NPs and

quantified DPs would be Quantifier Phrases, and would differ only in that the

complement of a Quantifier like tous 'all' is a DP, whereas the complement of

a Quantifier like plusieurs 'several' is an NP. Predeterminer Quantifiers

would then differ from prenominal Quantifiers in respect of their complementselection (i.e. subcategorisation) properties, viz. in respect of whether they

select an NP or DP complement.

Moreover, analysing Quantifiers as the heads of their containing phrases

would also provide us with a natural account of the fact that most Quantifiers

can be used not only prenominally, but also pronominally - as examples such as

the following illustrate:

(47)(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

Many (miners) died in the accident

Few (politicians) tell the truth

Both (students) failed their exams

Neither (one) is perfect

Given our assumption that each separate head within a nominal structure has a

pronominal counterpart, it follows that we should expect to find not only

pronominal N heads like one, and pronominal D heads like these/they, but also

pronominal Q heads like many/few/both/all etc. The difference between a

prenominal Quantifier like no and a pronominal Quantifier like none would then

be one of complement-selection, in that no requires an overt NP complement

(cf. 'no student of Linguistics') whereas none does not select an overt NP

complement (cf. *'none student of Linguistics').

An interesting issue which arises in relation to the twin assumptions that

determinate nominals are projections of a head D constituent and quantified

nominals are projections of a head Q constituent is whether or not nominals

which are indeterminate and unquantified should be analysed as headed by a

null Determiner or null Quantifier. Chomsky (1965, p. 107-8) explicitly

assumes that indeterminate nominals are premodified by a null Determiner: some

empirical evidence in support of this assumption might seem to come from

examples such as the following:

(48)

Linguists take themselves/*ourselves/*yourselves too seriously,

don't they/*we/*you, the/*we/*you poor fools?

In the context of our earlier discussion of examples such as (41) above, it is

interesting to note that the indeterminate nominal linguists is intrinsically

third person in nature, since it can serve as the antecedent of a third (but

not second or first) person anaphor like themselves, and can be tagged by a

third (but not second or first) person pronoun like they or by a nominal

headed by a third (but not second or first) person Determiner like the. Given

our earlier arguments that the person properties of nominals are carried in

their Determiner system, a natural way of accounting for the fact that

indeterminate nominals are intrinsically third person is to suppose that they

are headed by a null third person Determiner, so that a seemingly

indeterminate nominal such as linguists is in fact a determinate nominal of

the simplified form (49) below (where e represents a null head):

(49)

[DP [D e] [NP [N linguists]]]

Of course, there are also other ways of handling the relevant data - e.g. to

suppose that third person is a default value, so that any nominal which is not

headed by a first or second person Determiner is (by default) analysed as a

third person expression.

In much the same way, we might suppose that nominals such as those

italicised in (50) below:

(50)

I'd like salad/potatoes with the main course

is a QP headed by a null (partitive) Quantifier which takes the NP

salad/potatoes as its complement. If we posit such a null partitive

Quantifier, then in order to account for the ungrammaticality of sentences

such as:

(51)

*I'd like sweet after the main course

we shall have to suppose that this null partitive Quantifier may select an NP

complement headed by a mass Noun like salad or a plural Noun like potatoes,

but not an NP complement headed by a singular count Noun like sweet. In this

respect, the null Quantifier would resemble the overt Quantifier enough in its

complement-selection properties: cf.

(52)

Have you had enough salad/potatoes/*sweet?

The fact that our putative null partitive Quantifier has the same complementselection properties as a 'real' Quantifier such as enough increases the

plausibility of positing its existence.

One type of nominal constituent whose syntax we have not so far considered

are adnominal Adjectives. Under the classic NP analysis (cf. e.g. Radford

1981/1988), both prenominal attributive Adjectives and postnominal Adjectives

were analysed as adjuncts to the sister nominals which they are immediately

adjacent to, and thus occupy the same hierarchical position (differing only in

their linear position). A natural extension of this analysis within the DP

framework would be to posit that such Adjectives head APs which function as

adjuncts to the NPs they modify. In more concrete terms, what this would mean

would be that the bracketed nominals in sentences such as (53) below:

(53)(a)

(b)

[Available funds] are limited

[Funds available] are limited

would have the simplified adjunction structures indicated in (54) below:

(54)(a)

[NP [AP available] [NP [N funds]]]

(b)

[NP [NP [N funds]] [AP available]]

Treating adnominal adjectival expressions as APs which serve as adjuncts to

NPs in this way offers the obvious advantage of providing a unitary account of

the syntax of prenominal and postnominal Adjectives. Moreover, the adjunct

analysis correctly predicts that postnominal APs (being adjuncts external to

NP) will follow postnominal arguments (which are internal to NP), as we can

illustrate in terms of examples such as the following:

(55)(a)

(b)

[students of Linguistics] good at Phonetics

*[students good at Phonetics of Linguistics]

If (as we are suggesting here) of Linguistics is a complement of students, and

good at phonetics is an adjunct to the NP students of Linguistics, then the

word order facts in (55) fall out in precisely the way we should expect them

to.

However, a closer look at examples like (54) should alert us to a potential

problem - namely that available licenses a PP complement to us when used

postnominally, but not when used prenominally. Moreover, this is not in any

sense a lexical idiosyncrasy of the Adjective available, since the same is

true of other Adjectives (e.g. suitable and proud) as we see from paradigms

such as:

(56)(a)

(b)

(c)

resources available to us/*available to us resources

people suitable for the job/*suitable for the job people

mothers proud of their children/*proud of their children mothers

Abney (1987 p. 326) argues that it is a systematic fact about English that

'prenominal Adjectives may not have complements'. The obvious question to ask

is how we are to account for this under the adjunct analysis.

Abney (1987) suggests that the reason why prenominal Adjectives do not

permit complements is that the Noun Phrase premodified by the Adjective is

itself the complement of the Adjective. What this means is that prenominal

Adjectives are the heads of their containing phrases, and that the Noun

Phrases which they modify are the complements of the head Adjectives. If we

continue to suppose that postnominal adjectivals are adjuncts, then this would

mean that nominal pairs such as available resources and resources available to

us would have the respective simplified structures indicated in (57) below:

(57)(a)

(b)

[AP [A available] [NP [N resources]]]

[NP [NP [N resources]] [AP [A available] [PP to us]]]

Prenominal Adjectives would thus be the heads of their containing phrases,

whereas postnominal Adjectives would be adjuncts to the nominals they follow.

A structure such as (57)(a) would involve complementation (since a modified

nominal is analysed as the complement of the Adjective which modifies it),

whereas a structure such as (57)(b) would involve adjunction (with the

adjoined AP having an essentially predicative interpretation, and thus being

interpreted in much the same way as a restrictive relative clause like that

are available to us).

There are a number of interesting phenomena which lead us to the conclusion

that attributive (premodifying) Adjectives exhibit different syntactic

behaviour from predicative Adjectives, and that postmodifying Adjectives are

used in an essentially predicative way. For example (as noted in Jackendoff

1972), Adjectives like mere and utter can be used prenominally, but not

postnominally or predicatively: cf. e.g.

(58)(a)

(b)

(c)

mere excuses/utter chaos

*excuses so mere/*chaos so utter

*His excuses were mere/*The chaos was utter

Conversely, there are Adjectives which can be used postnominally or

predicatively, but not prenominally: cf.

(59)(a)

(c)

people afraid of the dark

*afraid people

(b)

They were afraid

Some Adjectives carry one meaning when used prenominally, but another when

used postnominally or predicatively: cf.

(60)(a)

(b)

(c)

present students (antonym = past)

students present (antonym = absent)

Most of them are present (antonym = absent)

What is particularly interesting about such data is that they suggest that

postnominal Adjectives are essentially predicative in nature, and distinct in

a number of ways from prenominal Adjectives. Clearly it would be difficult to

provide any systematic description of the semantic differences between

prenominal and postnominal Adjectives if we were to posit that the two have

the same function of adnominal adjuncts.

Further support for the claim that prenominal Adjectives are the heads of

their containing nominals comes from the fact prenominal Adjectives often

combine with following NP complements to form an unit with an idiosyncratic

(metaphorical) meaning which is not present when the Adjective is used

postnominally or predicatively. It is a feature of head+complement structures

that they often have a metaphorical interpretation, as we see from expressions

such as 'break the ice', 'blow the whistle', 'smell a rat', 'kick the bucket',

'spill the beans', 'toe the line', 'bite the bullet', 'bite the dust', 'hit

the roof', etc. Significantly, many Adjective+Noun collocations also have an

idiosyncratic metaphorical meaning - e.g. 'white elephant', 'red herring',

'blue stocking', 'grey matter', 'black sheep', 'cold turkey', 'hot rod',

'humble pie', 'blank cheque', 'sacred cow', 'damp squib', 'flying saucer',

'wet blanket', etc. However, the idiomatic interpretation is lost if the

Adjective is used postnominally or predicatively, so that a sentence such as

'It was a red herring' can have the idiomatic interpretation 'It was

irrelevant', but not a sentence such as 'It was a herring red as any I had

ever come across', nor a sentence such as 'The herring was red'. Given that

many head+complement structures are idiomatic collocations, treating

prenominal Adjectives as the head of their containing nominals would provide

us with a straightforward account of the fact that such prenominal Adjective

collocations have an idiosyncratic metaphorical interpretation. Much the same

point can also be made in relation to the fact that many prenominal Adjectives

take on an idiosyncratic metaphorical meaning when combined with a specific

(non-metaphorical) nominal complement - cf. expressions such as 'white lie',

'black market', 'purple prose', 'spitting image', etc.

A further way in which prenominal and postnominal Adjectives may differ is

in respect of their morphosyntactic properties. For example, in French (where

Adjectives carry overt AGR properties), we find that prenominal Adjectives may

exhibit different agreement patterns from postnominal or predicative

Adjectives. In this respect, consider the following contrast:

(61)(a)

de vieilles gens 'some old [FPL] people'

(b)

des gens qui sont plus vieux que moi 'some people who are#more

old [MPL] than me'

(c)

des gens plus vieux que moi 'some people more old [MPL] than me'

The Noun gens 'people' is feminine in French, but has the semantic property of

denoting mixed sex groups. Since masculine is the unmarked gender in French,

expressions predicated of such nominals generally take masculine plural

agreement - hence the use of the masculine form vieux in (61)(b) and (c): this

pattern of agreement is loosely termed semantic in traditional grammar.

However, prenominal Adjectives require strict syntactic agreement (i.e.

agreement with the number/gender properties of the head Noun of their NP

complement), so that the feminine form vieilles is required in (61)(a). It

would seem that it is not unusual to find that modification requires strict

syntactic agreement between a modifying and a modified head; by contrast,

predication often seems to require a relation of 'semantic compatibility'. The

two different agreement patterns can be illustrated in terms of an English

sentence such as 'This parliament have decided to reject the proposed bill'.

Here, we have strict syntactic agreement between the modifier this and the

Noun parliament which it modifies, but a relation of 'semantic compatibility'

between the singular subject this parliament and the plural head Auxiliary

have of the predicate phrase.

Under Abney's analysis, Adjectives can be used either as modifiers which

select an NP complement (as in proud woman), or as predicates which select a

PP or CP complement (as in proud of her son or proud that he won). The

ungrammaticality of strings such as:

(62)

*a proud of her son woman

is then attributable to the fact that no Adjective can function simultaneously

as both a predicate (taking an PP complement like of her son) and a modifier

(taking an NP complement like woman). Word order facts (e.g. the fact that

prenominal Determiners precede prenominal Adjectives) are determined by the

complement-selection properties of specific categories. For example, in order

to handle the word-order facts in a structure such as:

(63)

[DP [D a] [AP [A big] [NP [N dog]]]]

Abney posits that D selects either an AP complement like big dog or an NP

complement such as dog, and that A (when used attributively) selects an NP

complement.

However, Abney's core assumption that both predicative Adjectives and

(prenominal) attributive Adjectives are the heads of containing Adjectival

Phrases poses the problem that it predicts that the two behave in the same way

in every respect. And yet, this is not the case at all. For example, although

an attributive AP can be used as the complement of a Determiner, a predicative

AP cannot - as we see from examples such as the following:

(64)(a)

(b)

Mary is a proud woman

*Mary is a proud

Similarly, attributive Adjectives can be recursively stacked but predicative

Adjectives cannot be: cf.

(65)(a)

(b)

Mary is a proud young woman

*Mary is proud young

Conversely, a predicative AP can be used as the complement of be but not an

attributive AP: cf.

(66)(a)

(b)

She is proud of her son

*She is proud woman

The contrasts between the (a) and (b) sentences in (64-66) cannot be handled

in any straightforward fashion given the assumptions we have made thus far.

Analysing both predicative and attributive adjectival expressions as APs

wrongly predicts that the two exhibit the same syntactic behaviour - and yet

this is clearly not the case. What we need is some way of capturing the fact

that when used as prenominal modifiers, Adjectives behave rather differently

than when used as predicates. But how can we do this?

Abney (1987) suggests an interesting answer to this question in terms of

the notion of inheritance. His proposal amounts to positing that prenominal

Adjectives are modifiers, and that it is a general property of phrases headed

by modifiers that they inherit the categorial status of their complements.

Implicit in this analysis is the postulation of a principle such as the

following (The suggested characterisation here is my own: Abney offers no

specific formulation):

(67)

INHERITANCE PRINCIPLE

A modifier phrase (i.e. a phrase headed by a modifier) inherits the

categorial properties of its complement

What such a principle in effect says is that the properties of a modified

expression percolate up to projections of the modifier. Given this principle,

a string such as big dog will have the intrinsic categorial status of an

Adjectival Phrase, but (being a modifier phrase headed by the modifying

Adjective big) will inherit the NP-hood of its complement dog, and so acquire

the inherited categorial status of a Noun Phrase.

Consider how we might use the INHERITANCE PRINCIPLE (allied to Abney's

assumptions) to handle the data in (64-66) above. Let us assume that both

Determiners and attributive Adjectives select an NP complement, and that

selection is sensitive to the inherited categorial properties of items. It

then follows that the string a proud woman in (64)(a) is grammatical because

the Determiner a selects as its complement a string (proud woman) which

becomes an NP by inheritance (although intrinsically an AP): by contrast, the

string *a proud in (64)(b) is ungrammatical precisely because proud is an AP

(It has no NP complement, and so cannot become an NP by inheritance), and D

selects an NP complement, not an AP complement. The possibility of recursively

stacking attributive Adjectives in a string like a proud young woman in

(65)(a) is predicted under the inheritance analysis, if we assume that

attributive Adjectives select an NP complement: the string young woman is

intrinsically an AP but becomes an NP by inheritance, and so can serve as the

complement of another attributive Adjective like proud so resulting in the

string proud young woman which is intrinsically an AP, but which inherits the

inherited NP-hood of young woman, so that the whole string proud young woman

itself becomes an NP by inheritance (and so is able to serve as the complement

of another attributive Adjective, or of a Determiner like a). By contrast,

since predicative Adjectives select only a PP or CP complement (never an AP

complement), the ungrammaticality of (65)(b) *Mary is proud young can be

accounted for in terms of a violation of complement-selection requirements.

The data in (66) can be handled straightforwardly if we assume that be selects

an AP complement but not an NP complement, since proud of her son will be an

AP (predicative Adjectives do not fall within the scope of the INHERITANCE

PRINCIPLE, since they are not modifiers), but proud woman will become an NP by

inheritance.

Interesting though the inheritance analysis is, it is potentially

problematic in a number of respects. For example, Abney implicity treats

prenominal Determiners as modifiers (which means that a DP such as a theory

inherits the NP-hood of its complement theory and so becomes an NP by

inheritance): but given that (as we have already seen) the inheritance

analysis predicts that modifiers can be recursively stacked, this predicts

that not just prenominal Adjectives but also prenominal Determiners can be

recursively stacked: however, this prediction is false - as we see from the

ungrammaticality of *a my idea, *that the house etc. in English.

Moreover, the key assumption that complement-selection is sensitive to

inherited categorial properties proves problematic in relation to data such as

the following (from French):

(68)(a)

(b)

On a choisi des vins (excellents)

We have chosen some wines (excellent)

'We chose some (excellent) wines'

On a choisi d'excellents vins

We have chosen some excellent wines

'We chose some excellent wines'

As these examples illustrate, in non-negative sentenes in French, the

partitive Quantifier des 'some' is used to quantify both an unmodified plural

NP, and a plural NP modified by a postnominal Adjective; by contrast, the

different partitive Quantifier d(e) 'some' is used to quantify a plural

nominal modified by a prenominal Adjective. However, the problem posed for the

inheritance analysis by such data is that the strings vins and vins excellents

will be NPs intrinsically, while the string excellents vins will be

intrinsically an AP but will become an NP by inheritance. Given Abney's

assumption that the inherited categorial properties of a constituent override

its intrinsic properties with respect to complement-selection, it follows that

all three strings vins, vins excellents and excellents vins will be treated

as NPs for complement-selection purposes. But this leaves us with no

straightforward way of accounting for the fact that des is required in

structures like (68)(a) but de in structures like (68)(b), since in both cases

the Quantifier will select a constituent which is an NP (intrinsically in the

(a) structure, by inheritance in the (b) structure). A number of other

problems posed by the inheritance analysis are discussed in Radford 1989.

Given the problems associated with the inheritance analysis, we might

explore an alternative approach to the problem. The intuition which is being

captured by saying that a complex constituent such as big dog is an AP

intrinsically but becomes an NP by inheritance is that big dog is an

adjectival expression, but one in which the nominal features of dog percolate

up to overall phrasal constituent, which therefore has the status of an

Adjective-modified Noun Phrase. The implicit assumption behind this analysis

is that modified expressions are co-headed: one way of capturing this

intuition would be to say that the head of the modifying Phrase is the

immediate head of the overall constituent, and the head of the modified Phrase

is its ultimate head. In these terms, the immediate head of a string such as

big dog would be the Adjective big, but its ultimate head would be the Noun

dog. One way of formalising this (suggested in Radford 1991) would be to

suggest that big dog is an ANP constituent, i.e. a double-bar constituent

whose immediate head is A, but whose ultimate head is N. In contrast, an

unmodified nominal such as students (of Linguistics) would be an NP, i.e. a

constituent whose immediate and ultimate head is the same Noun, students.

Given these assumptions, it would be a simple enough matter to handle the

contrast between des and de in (68), by saying that des quantifies (i.e.

selects as its complement) an NP constituent, whereas de selects an ANP

constituent.

An obvious question to ask is whether we could extend the coheadedness

account to deal with multiply modified phrases such as all the brown dogs. One

possibility would be as follows. We might suppose that dogs is an NP, i.e. a

constituent whose immediate and ultimate head is the same Noun dogs. We might

also suppose that brown dogs is an ANP (an Adjective-modified Noun Phrase), in

that its immediate head is the Adjective brown, and its ultimate head is the

Noun dogs. We might further suppose that the brown dogs is a DNP (Determinate

Noun Phrase), i.e. a Phrase whose immediate head is the Determiner these and

whose ultimate head is the Noun cars. Finally, we might suppose that the

overall expression all the brown dogs is a QNP (Quantified Noun Phrase), i.e.

a Phrase whose immediate head is the Quantifier all and whose ultimate head is

the Noun cars. Given these assumptions, the string all the brown dogs would

have the simplified structure (69) below:

(69)

[QNP [Q all] [DNP [D the] [ANP [A brown] [NP [N dogs]]]]]

We could then attain a unitary characterisation of the notion of a nominal

constituent as a 'constituent whose ultimate head is a Noun'. Thus, the NP

dogs, the ANP brown dogs, the DNP the brown dogs and the QNP all the brown

dogs would all be 'nominal constituents' in (69). For some thoughts on how

this analysis might be extended, see Radford 1991.

REFERENCES

Abney, S.P. 1987. The English Noun Phrase in Its Sentential Aspect. PhD diss:

MIT

Chomsky, N. 1965. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press

Chomsky, N. 1986. Barriers. Cambridge: MIT Press

Chomsky, N. 1989. Some Notes on Economy of Derivation and Representation. In

I. Laka and A. Mahajan (eds) Functional Heads and Clause Structure. MIT

Working Papers in Linguistics 10: 43-74

Fassi Fehri, A. 1988.

Generalised IP structure, Case, and VS word order.

In Fassi Fehri, A., Hajji, A., Elmoujahid, H. and Jamari, A. (eds)

Proceedings of the First International Conference of the Linguistic Society

of Morocco. Editions OKAD: Rabat, pp. 189-221

Fukui, N. 1986. A Theory of Category Projection and its Applications. PhD

diss: MIT

Harris, M (1991) 'Demonstrative Adjectives and Pronouns in a Devonshire

dialect', in Trudgill and Chambers, pp. 20-28

Hoekstra, T. 1984. Transitivity: Grammatical Relations in Government-Binding