Scottish Needs Assessment Programme

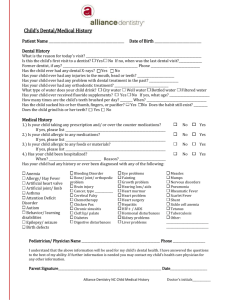

advertisement