Steve Killen

advertisement

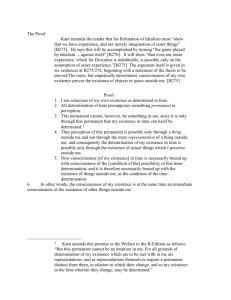

Steve Killen 11 Oct 05 Phil 373 “Idealism despite myself” The three basic positions that encompass the views that we are able to have concerning the nature of our ideas about the world are realism, anti-realism, and idealism. The spectrum that they represent is the degree of certainty to which we may claim the existence of an actual world beyond our perceptions. Materialist realism is on one end, asserting both the existence of a world that our senses perceive and our ability to learn about this world. Moving along the spectrum, anti-realism is in agreement with the existence of a world corresponding to our sense data, but asserts that our ability to know what the objects of our senses are in and of themselves is plainly lacking. And over there, on the far end of the room, away from everyone else in the room, sitting on the group W bench, is idealism. The general form of idealism rejects the assertion of the world's existence separate from mind(s), mental activity, or perception: everything that can be said to exist is an idea. To the ordinary person, who may be described as a realist, this means that nothing really exists in and of itself. Now, a peanut-butter and jelly sandwich may sound like a good idea, but any normal individual would prefer to have an actual PB & J to satisfy his actual peckishness at 2am. Fortunately, it turns out that the idealist conception of reality is perfectly compatible with enjoying a late night snack. First, why is realism the general trend of thought? It does answer a great number of questions that would otherwise pester us endlessly, such as why we can't breathe underwater. At first blush, it causes us the least amount of mental strain to consider the data that we receive through our senses as being genuine, true, and giving us useful information. But when one stops to consider the matter in the manner of John Locke, one may realize that this conception of the world is merely taking the senses for granted. He analyzed the objects of perception, and came up with categories by which we can classify them. Secondary qualities are the ones that are dependent on our perception of them (e.g., color, smell, texture), and primary qualities are intrinsic to the objects (e.g., shape, duration). However, this is where he could go no further, and by stopping laid out the basic problem of realism: how do we know that what we call primary qualities are actually intrinsic to the objects themselves? His answer was that we don't; we just call it Substance and move on to tea and scones. Anti-realism takes the ball and runs with it, though. From an anti-realist perspective, not only are we more or less unable to know what things are at their fundamental level, but in addition, all of our knowledge is strictly limited to the manner in which we perceive the world. To the antirealist, we can build scanning electron microscopes and neutrino detectors to our hearts' content, but all we can say about the data we receive is that we interpret it a certain way. This is more in line with Charles Peirce's pragmatism: we interpret our sense data as the world around us because it continues to be consistent with our experience of it through the senses, but there is no guarantee that our senses are representing the world exactly as it is. This doesn't engender any problems with PB & Js, as long as you're comfortable in the knowledge that you don't know what a PB & J sandwich really is. The difficulty that anti-realism is susceptible to, which it shares with realism, is that of the existence of the world in any case, no matter what we may perceive it to be. George Berkeley first illustrated this in his response to Locke's distinction between primary and secondary qualities, and showed that in the end, both are in fact reliant on our perception of them. If there is no difference between them, then no claim whatsoever may be made about their existence as anything other than ideas of shape, color, or any other perceived characteristic. So, all of the things that we perceive must be a product of mental activity, or dependent on a mind. It is a firm denial of realism and anti-realism's shared assumption, on the grounds that we have no means by which to test it. On its face, idealism is susceptible to solipsism, as the thinker who thinks that all sense data is a product of his mind has no ability to account for any other entity than himself. But I think this puts the situation into a false dichotomy, begging the question of whether a world exists beyond the mind to answer why we act as if a world existed beyond the mind. The only thing that idealism claims is that our notion of existence is dependent on mental structure--we simply have no grounds to talk about existence of anything beyond that framework. The real problem that this line of thinking uncovers is the one that the other models don't have an opportunity to address—given our interaction with other minds, how is our collective perception so incredibly consistent if not for an objective, external world? Resorting to objective reality lacks any substantiation other than the circular logic of our perception. Without this tool, though, idealists have a hard road ahead of them. Most address it by asserting a universal Mind of one stripe or another, through or within which all ideas are formed and shaped. (It is, I think, at this point that most realists on the rollercoaster clamor to be let off.) Berkeley chose God, Spinoza and Hegel chose the Absolute Mind. These are two different approaches, and I think each concept has some merit. However, these seem to be equally without foundation for precisely the same reason as the realist’s position: each is still another claim of substance, without any means to justify its assertion other than it fits the data. The pragmatic approach of an anti-realist’s position on our knowledge of the world is adoptable by an idealist: we have no way to know, so it’s better that we simply make no claims. Considering the existence of the universe has always made my head hurt. When I think about the idea of “universe”, generated by a logical step from living in my own sphere of influence, I am immediately forced to think about beginning, end, inside, outside, and a whole host of things not suitable for print. This is a direct result of our use of language, and points to the emptiness of its referent. One may talk about infinity, but language is based on the concrete exigency of the here and now. Although realists can claim to be able to talk about objects independent of minds, it is none other than minds that are doing the talking. Any attempt to break out of this is futile—the notion of existence and non-existence is restricted to the domain of thought. Our investigations in the scientific realm are bearing out the evidence of this. Einstein put it very simply: energy equals matter. While physicists claim to have observable data indicating that the universe is infinite (in fact, a potato-chip-shaped infinity), they have yet to explain a coherent theory of what it means for the universe to be infinite. Religions, too, have attacked the foundations of the universe, and are similarly left wanting. Theistic or entity-based conceptions are best categorized as realist or anti-realist*, despite Berkeley and Spinoza's efforts to the contrary--these, too fall into the trap of supposing a plane of some unknowable substance despite a total lack of demonstration. An idealist’s view (that the universe is a construct of our mind) is able to leap beyond the constraints of language by recognizing that language, and therefore ideas, are the only means by which we can communicate. It hearkens back to Socrates' earnest and profound maxim: to not suppose one knows something that one does not, in truth, know. All we can correctly say about the world is that we can refer to things as existing. That the referrer be human is not required; anything that forms a conception of discrete things is using language to do so. Any further claim, i.e., that things exist outside of a conception of their existence, is to take a long walk off the short pier of the unsupportable. * “Before I had studied Zen for thirty years, I saw mountains as mountains and waters as waters. When I arrived at a more intimate knowledge, I came to the point where I saw that mountains are not mountains, and waters are not waters. But now that I have got its very substance I am at rest. For it’s just that I see mountains once again as mountains and waters once again as waters.” (Ch'ing Yuan, 8 th century Ch'an Buddhist teacher) It is also unnecessary to reject idealism on the supposition that one must behave differently in the world. It is a simple fact that we exist and interact, and each of the three domains of metaphysics is compatible with this. Precisely how it is the case that we accomplish the feat of self-aware existence is not sufficiently answerable, though, despite Sprigge's claim to the contrary. It seems as if one of two things is true: either we exist in a wholly real and pluralistic universe, in which case there can be no such thing as mind, or we exist in a wholly mental and monistic universe, in which to talk about an objective reality is just to talk about another relation of ideas. To answer the problem by way of a dualistic mind-body construction is to beg the question from one side of the fence or the other, but to answer it at all is also reaching too far. In the end, no matter whether you are a realist, anti-realist, or idealist, sun is warm and grass is green. Thus it is perfectly natural to enjoy the taste of fresh raspberry jam and Skippy super-crunch on cracked whole wheat bread even if one can't claim to say that the sandwich and the person eating it are anything other than ideas. Once you have dropped the effort to explain reality outside of language, which in itself is a contradiction in terms, you have gained a freedom from worry that realists and anti-realists may not have.