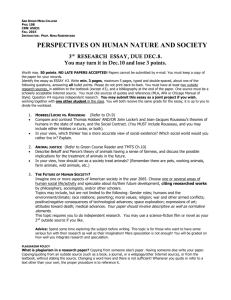

ATan Reading Response to Chapter 1 of War Before Civilization

advertisement

Amy Tan Reading Response February 13, 2009 Response to War Before Civilization In the first chapter of War Before Civilization, Lawrence Keeley lays out the discursive framework in which war in “primitive” societies was waged. Keeley describes the Hobbesian idea of the short and brutish life and Rousseau’s Noble Savage in the state of nature, and how both of these myths were rearticulated in explanations for the causes of warfare in recent discourse. Keeley also describes how in anthropology, the trend has been to increasingly pacify the human past, and that even archaeologists have come to “ignore the bellicosely obvious for the peaceably arcane.” Although Keeley gives a good sense of what discourse about “primitive” warfare has been he is vulnerable to a few criticisms. The first of those is that it is unclear how he defines civilization and the second is about the assumptions he makes about Hobbes and Rousseau, meaning that it is unclear how he’s going to regard the Hobbes and Rousseau’s interpretation of history. Will they be treated as myths by which to measure anthropological facts against or as markers of their times or both? The strengths in Keeley’s argument are his treatment of Hobbes and Rousseau’s ideas about pre-civilized warfare and how these ideas were re-articulated and strengthened depending on the state of “civilized” warfare. Keeley explains that Hobbes came to the conclusion that man lived in a state of war because of constant competition, and that war could not be avoided between men until certain covenants were made. When governments or monarchy was established, man’s humanity came to the fore. Keely comments that this idea became popular during colonialism, and often served as justification for brutish acts against native populations. Keeley describes Rousseau’s argument as almost the opposite of Hobbes, since it regards the “civilizing process” as a detriment since it corrupts the peaceful nature of the Noble Savage. Rousseau argues that when left in a state of nature, mankind would live in peace with itself and nature, except in the case of hunger. Rousseau’s idea of a pacified past gained resurgence, according to Keeley, at the end of the 21st century in light of the horrors of the two world wars when studying “primitive” cultures. (Note: I did have one question, however, about the people applying these ideas of primitive existence – did they believe that they were studying others or people similar to their own ancestors?) Keeley, therefore, effectively establishes the two trends that have persisted when analyzing and explaining early warfare. Nevertheless, addressing certain key points would strengthen Keeley’s argument. The first of these is the question of defining civilized and primitive. From the text it appears as if Keeley means pre-civilized peoples were preliterate and tribal. He writes, for instance that at “the dawn of the European expansion (AD 1500) only a third of the inhabited world was civilized; all of Australasia and Oceania, most of the Americas, and much of Africa and north Asia remained preliterate and tribal” (Keeley 4). Furthermore, from the first chapter, I found Keeley’s assumptions about how to analyze (neo-) Hobbesian and (neo-) Rousseau-ian perspectives on early warfare unclear. Keeley does make the point that depending on the period (colonial or postwar), certain readings of history became more popular. At the same time, however, he seems as if he might just go onward with the two perspectives in his own analysis of pre-civilized warfare, without offering an alternative. Since I haven’t read the whole book, this criticism could be totally of the mark. While thorough in some ways, the text left me with a lot of questions about early warfare and the two myths: Why and how have these simplistic explanations endured – is it a case of Occam’s razor in which the simplest solutions suffice? What are the other frameworks when analyzing early warfare and early societies? Is it useful to talk about violence in “pre-civilized” society in the same ways we talk about it now? Is it fair to make the comparisons? Can we use the same vocabulary we use to describe the present as that we use to (re)imagine the past?