SOUND BITES HAPPY HOLIDAYS 2009 THE TRUE STORY OF

advertisement

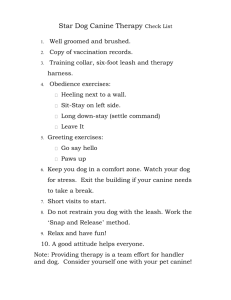

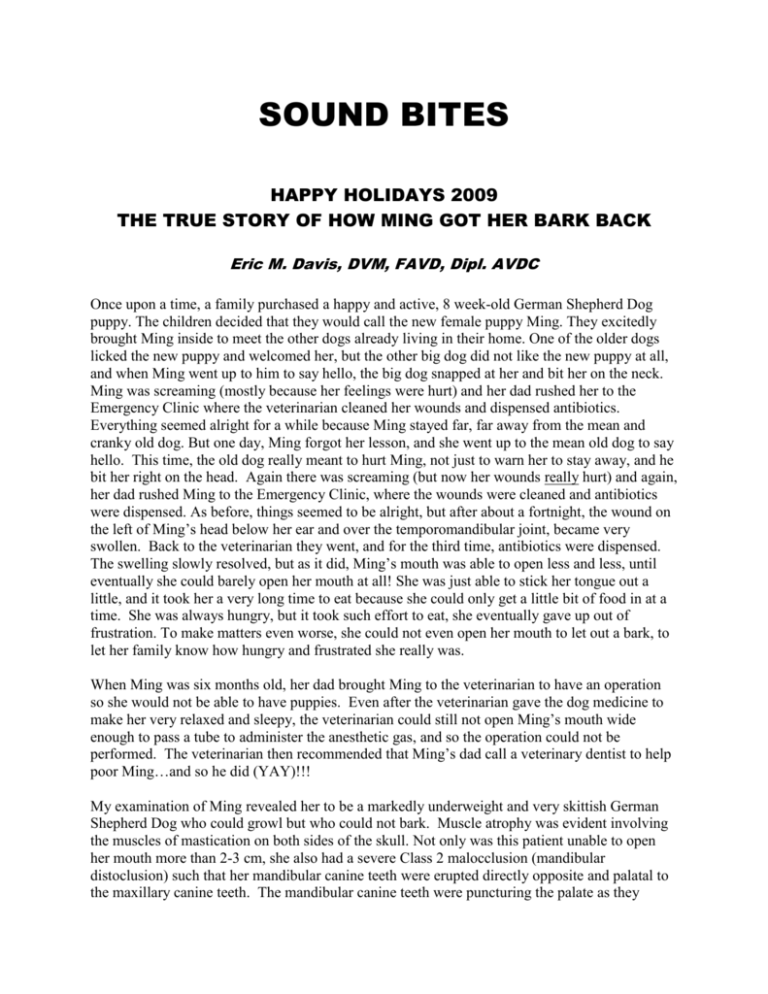

SOUND BITES HAPPY HOLIDAYS 2009 THE TRUE STORY OF HOW MING GOT HER BARK BACK Eric M. Davis, DVM, FAVD, Dipl. AVDC Once upon a time, a family purchased a happy and active, 8 week-old German Shepherd Dog puppy. The children decided that they would call the new female puppy Ming. They excitedly brought Ming inside to meet the other dogs already living in their home. One of the older dogs licked the new puppy and welcomed her, but the other big dog did not like the new puppy at all, and when Ming went up to him to say hello, the big dog snapped at her and bit her on the neck. Ming was screaming (mostly because her feelings were hurt) and her dad rushed her to the Emergency Clinic where the veterinarian cleaned her wounds and dispensed antibiotics. Everything seemed alright for a while because Ming stayed far, far away from the mean and cranky old dog. But one day, Ming forgot her lesson, and she went up to the mean old dog to say hello. This time, the old dog really meant to hurt Ming, not just to warn her to stay away, and he bit her right on the head. Again there was screaming (but now her wounds really hurt) and again, her dad rushed Ming to the Emergency Clinic, where the wounds were cleaned and antibiotics were dispensed. As before, things seemed to be alright, but after about a fortnight, the wound on the left of Ming’s head below her ear and over the temporomandibular joint, became very swollen. Back to the veterinarian they went, and for the third time, antibiotics were dispensed. The swelling slowly resolved, but as it did, Ming’s mouth was able to open less and less, until eventually she could barely open her mouth at all! She was just able to stick her tongue out a little, and it took her a very long time to eat because she could only get a little bit of food in at a time. She was always hungry, but it took such effort to eat, she eventually gave up out of frustration. To make matters even worse, she could not even open her mouth to let out a bark, to let her family know how hungry and frustrated she really was. When Ming was six months old, her dad brought Ming to the veterinarian to have an operation so she would not be able to have puppies. Even after the veterinarian gave the dog medicine to make her very relaxed and sleepy, the veterinarian could still not open Ming’s mouth wide enough to pass a tube to administer the anesthetic gas, and so the operation could not be performed. The veterinarian then recommended that Ming’s dad call a veterinary dentist to help poor Ming…and so he did (YAY)!!! My examination of Ming revealed her to be a markedly underweight and very skittish German Shepherd Dog who could growl but who could not bark. Muscle atrophy was evident involving the muscles of mastication on both sides of the skull. Not only was this patient unable to open her mouth more than 2-3 cm, she also had a severe Class 2 malocclusion (mandibular distoclusion) such that her mandibular canine teeth were erupted directly opposite and palatal to the maxillary canine teeth. The mandibular canine teeth were puncturing the palate as they erupted, a situation magnified because of the inability to open the mouth. Somehow, I would have to get the dog’s mouth to open. Once the mouth was opened wide enough for me to work, I anticipated that I would perform crown reductions on the mandibular canine teeth, followed by vital pulp therapy to permit the root ends of those teeth to complete their development (apexogenesis). The deep wounds in the palate would also need to be explored and closed surgically if oronasal communication were discovered. I can hear some of you asking “why not just ‘pull’ the lower canines”? My answer is that once the mandibular canine teeth have been removed, the bone of the rostral mandibles will atrophy because the bone no longer has a job to do if there are no teeth to support (Wolff’s Law). Therefore, the result of mandibular canine tooth extraction would be to further shorten the already shorter lower jaw, and would undoubtedly lead to persistent exposure of the tongue and drooling. Now, back to my story… why was the mouth unable to be opened and how would I solve that problem? The differential diagnoses for inability to open the mouth include masticatory myositis, temporomandibular joint ankylosis, craniomandibular osteopathy, tetanus, retrobulbar cyst or abscess, caudal zygomatic arch fractures, and neoplasia1 Radiographs of the skull provided by the referring veterinarian revealed altered bone architecture involving the left TMJ, and I was suspicious that either intra-articular or extra-articular joint ankylosis was present on the left side as a result of being bitten by the larger dog when Ming was a puppy. However, masticatory myositis, an immune-mediated disease directed against the unique muscle protein found only in muscles of mastication was also considered possible, as that disease has a high incidence in German Shepherd Dogs2. Although I recommended it, the owner declined serological testing to determine if antibodies against type 2M muscle protein were present in Ming’s serum. However the owner did authorize surgery to open the mouth, shorten the canine teeth and repair the deep holes in the dog’s palate. My plan called for initially using a stack of tongue depressors to gradually open the dog’s mouth wide enough to pass an endotracheal tube after intravenous induction of anesthesia. Alternatively, I was prepared to perform a tracheotomy if a tube of sufficient diameter could not be passed through the mouth. If the series of stacked tongue depressors did not sufficiently stretch what I hoped to be extra-articular scar tissue surrounding the left TMJ, I anticipated that I would approach the area surgically, and break down extra-articular connective tissue. If that maneuver were ineffective, unilateral condylectomy would be performed, and if that maneuver were ineffective, bilateral condylectomy would be my “fall back” position to open the mouth wide enough to treat the malocclusion. If TMJ surgery were necessary, I would harvest muscle tissue for biopsy to determine if masticatory muscle myositis was partially to blame for the patient’s inability to open her mouth. Following induction of general anesthesia, a series of tongue depressors were used to open the mouth wide enough to blindly pass a small diameter endotracheal tube from the mouth into the trachea. Even under a surgical plane of anesthesia, I could not force Ming’s mouth to open any more than 3-4 cm. Consequently, the left side of the face was prepared for surgery, and a curvilinear incision was made along the ventral border of the zygomatic arch over the left temporomandibular joint. Even after sharp and blunt dissection to expose the lateral aspect of the joint capsule, assessment of the range of motion revealed that the mouth could still not be opened more than 3-4 cm. Surgical exposure was then continued rostrally, a surgical length dental bur was used to initially score the bone, and an osteotome was used to subsequently resect the condyloid process from the vertical ramus of the left mandible. Immediately following unilateral condylectomy, the range of motion increased dramatically and the mouth was able to be opened 6-8 cm. Prior to closure, a portion of the masseter muscle was harvested and preserved for submission to the Comparative Neuromuscular Laboratory at the University of California, San Diego. Once I could open Ming’s mouth, I was able to obtain intraoral radiographs which confirmed that the root ends of the mandibular canine teeth had not yet completed their development, consistent with the dog’s chronological age. Crown reduction followed by partial vital pulpectomy, direct pulp capping, and composite restoration was performed on both mandibular canine teeth. The palatal wounds were then explored. The mandibular canine teeth had penetrated the soft tissue and the palatal shelf of the maxilla to a depth of 15 mm, such that the nasal cavity was separated from the oral cavity by just a scant layer of fibrous connective tissue on each side. After debridement and irrigation, a synthetic bone graft material (Consil®) was placed into the bony defects. Pedicle flaps were created, mobilized, and rotated to cover the bone grafts and were sutured into place. Only periosteum was left to cover the donor sites of the grafts which were left open to fill in by granulation tissue. At the ten day recheck exam, the owner reported that Ming “was a different dog”. Her tail was up, she exhibited more confidence, she was eating very well, and she was able to play with a ball and hold it in her mouth. Other than a small seroma over the condylectomy site, the surgery sites had healed very well, and the donor sites of the palatal flaps were already filling in with granulation tissue. Continued physical therapy of the jaw, including use of varying sizes of chew toys and multiple feedings of large-particle, dry dog food, was recommended to prevent fibrous ankylosis from occurring following condylectomy.3 Inflammation and fibrosis were identified in the biopsy of masticatory muscle tissue, consistent with the diagnosis of masticatory myositis. Despite the extent of fibrosis, corticosteroids were prescribed at an immunosuppressive dose, to limit additional damage by autoantibodies directed against remaining type 2M muscle fibers. Ming has a lot to be thankful for this holiday season…her teeth no longer puncture the roof of her mouth and her jaw is no longer frozen shut. But best of all, Ming has gotten her bark back! THE END 1 Rawlinson J. Tackling the canine and feline temporomandibular joint. Proc. 18th Ann Vet Dent Forum 2004:7-11. Marretta SM. Maxillofacial surgery. Vet Clin North Am Sm Anim Prac1998; 28: 1285-1296. 3 Anderson MA,Orsini PG, Harvey CE. Temporomandibular ankylosis: Treatment by unilateral condylectomy in two dogs and two cats. J Vet Dent 1996; 13 (1): 23-25. 2