Tutorial Module 4: Planning Learning Experiences

Note: This faculty development tutorial was created for the Educational Guidelines by Constance

Baldwin and the Guidelines team (Diane Kittredge, Miriam Bar-on, Patricia Beach, and Franklin

Trimm), with help from consultants, Carol Carraccio and Rebecca Henry. To access the original

files with active links, go to www.ambpeds.org/egweb; on the Menu of Options page, click on

Tutorials. PowerPoint versions of the tutorials are also available on the Guidelines website.

4a. Creating Educational Change in a Residency Program

Instructional planning for a residency program must be conducted with reference to the program

as a whole. Educational changes should take into account the program’s unique combination of

leaders, instructors, learners, patients, and institutional environment. This module on

instructional planning begins with a discussion of some of the systemic challenges and

opportunities that face an educational innovator.

The challenges. The educator who aims to plan new learning experiences for residents faces

some imposing challenges. First, although optimizing education may be your primary goal,

resident educators are always working within a system in which educational needs and

service demands must be balanced. Although residents may be avid to learn and grow, and

their faculty determined to help them become the best possible physicians, the health care

system nearly always places highest priority on service demands, sometimes at the expense of

education. At virtually all institutions, clinical services provide a critical funding stream that makes

educational programs possible.

In the ideal health care setting, optimal medical care provides the context for optimal health

professional training—after all, how could one expect good education to take place in a system

that isn’t working well for patients? In the real world of the hospital and clinic, however,

balancing between service and education is difficult for many reasons: resident and faculty time

is limited, patient flow fluctuates, scheduling is complex. On financial balance sheets, teaching

and learning are time consuming and insufficiently compensated. Given the constant juggling act

required to make a health care organization function, goals for resident education are most likely

to be met when they are aligned as much as possible with patient care goals.

Another challenge to the educator who aspires to improve resident education is that tradition is

a very powerful force in medical education—one that is often reinforced by the systems of

hierarchical power that commonly govern academic units. Whatever your educational expertise,

it takes considerable political skill to win a time and a place for new learning experiences within

an overloaded residency program and to persuade the faculty to take a risk with new teaching or

evaluation methods.

The opportunities. Despite these potential barriers, curricular change can be successfully

implemented. So how can an educational innovator work within the system?

1. For starters, you will need protected time to develop new programs and support and help

from your colleagues. A community of educators can often be won over to a plan for change

if it offers enough benefits to enough people. Times of change often create a friendly

environment for innovation, because people recognize the need for new ways to accomplish

old tasks. Educational change is much more palatable if it is seen to solve a recognized

problem (e.g., new accreditation requirements or governmental mandates), or meet a new

need (e.g., an emerging patient care problem), or offer fresh opportunities for intellectual

challenge or advancement to the faculty.

1

2. One seldom begins from the beginning—there is usually a program in place, and within it,

you can strategically identify areas of particular need or opportunity to help target

your initial efforts. Because program time is so tight, it is often easier to modify what exists

than create something de novo. With patience and careful planning, you can engineer

incremental changes that gradually build a significant innovation into an educational

program.

3. It is smart to identify resources to support an educational innovation. A grant-funded

project is nearly always easier to market to an institution than one that costs money. In the

absence of a grant, a marketing plan that details cost savings to offset new expenses can be

persuasive to program leaders.

4. In addition to these practical factors, the success of an educational innovation often depends

most on persistence and planning. A champion for the change who is supported by early

adopters is most likely to achieve success. Innovators who are very clear on their goals,

create a systematic implementation plan, deal creatively with obstacles, and stay focused on

their plan of action in spite of barriers are most likely to bring their project to fruition.

4b. Qualities of Sound Learning Experiences

Learning experiences come alive in the hands of a good teacher. This module deals with the

planning, rather than the delivery, of educational experiences, so it does not discuss teaching per

se. In all that follows, however, imagine your planned learning experiences as they will come to

life in a real teaching and learning environment. Educational quality can only be judged at the

interface between the mind of the teacher and the mind of the learner.

Authenticity. Physician education is built on the apprenticeship model, because expert

caregivers (and their patients) can offer an education that is unmatched in authenticity.

Therefore, learning experiences are typically organized around key aspects of the patient care

process, including the information seeking, evaluation, and application upon which good

evidence-based practice is built.

As adult learners, residents crave authentic, real world learning that meets their immediate need

to know. Realistic learning experiences also give them excellent opportunities to apply theory to

practice, observe realistic interactions between different types of caregivers, and practice lifelong learning skills.

In the past, the cornerstone of medical education was didactic teaching of factual knowledge by

faculty, often delivered in a physical setting apart from the busy clinical service, while upper level

residents taught less experienced residents “on the front lines” on wards and clinics. In the

current world of compliance-directed care, the focus is on faculty-guided, experiential learning in

the patient care arena, where one can address a full range behaviors and attitudes that are

linked to factual knowledge. Fortunately, compliance and accreditation requirements are in

concert here: the demand for more clinical involvement by faculty also makes it easier for them

to judge the competence of their learners. Residents must now apply their knowledge and prove

their competence by performance in an authentic patient care environment, under closer scrutiny

by their attending physicians.

Educational variety. Individual residents and students have different learning styles, just as

different educators have their own teaching styles. Although advanced learners are usually

flexible in how they learn, most have preferred styles that are optimal for their acquisition of new

knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Therefore, residency programs usually seek a balance between

different educational methods. Most include a combination of didactic instruction (lectures and

readings), interactive learning (role plays, team projects), and experiential learning (clinical

rotations, community experiences), and include both supervised with self-directed activities.

2

When choosing new experiences to develop for a program, you might review the balance of

learning activities currently in the program, and consider using teaching methods that are

underrepresented. Of course it is also important to match the teaching method to the educational

goal of the planned activity:

Didactic activities remain the most efficient way to teach complex sets of facts and

concepts (e.g., fluid dynamics, immunization schedules)

Interactive activities are well suited to teaching topics where multiple perspectives

deepen a learner’s understanding (e.g., barriers to access, multi-cultural care, end-of-life

care)

Experiential activities are ideal for teaching skills that need to be practiced in authentic

patient care settings (e.g., conducting an ear exam, interviewing an adolescent patient,

analyzing a dataset)

Ideally, a learning experience is planned to include choices among a variety of activities, so the

learner can self-select learning vehicles that match his/her preferences.

Richness and depth. Because educational programs for residents are intense and highly

concentrated, each individual learning experience needs to teach as efficiently and effectively as

possible. Residents are particularly demanding adult learners, because they are all veterans of

the educational game, yet bring quite varied skills and sophistication to their learning

experiences. Moreover, they are pressed for time, often impaired by lack of sleep, and typically

(when awake) have an urgent desire to learn what they need to know fast and without

flourishes. These learners call upon the best in us!

The following characteristics help to make educational activities more acceptable to the pressured

(and sometimes jaded) resident:

Activities for residents should promote self-directed learning that offers choices, so

they can make the experience fit their learning needs and interests. Their backgrounds

are variable even when they begin their training, and they take rotations at different

times of the year, when they are at different stages of maturation. Moreover, selfdirected learning during residency prepares physicians for a lifetime of continuing selfeducation. Residents need to develop independence in formulating questions and finding

and applying relevant information.

Active learning experiences provide more immediate and authentic learning for these

adult learners. Alternatives to passive learning are also more likely to keep them awake!

Interactive learning encourages residents to teach each other and build skills in

teamwork. Many residents are energized by interactive activities, either as competitors or

as collaborators. Active and interactive learning also facilitate longer retention of learned

material.

An ideal clinical experience is rich in teachable moments, so the instructor can take

the individual learner in several possible directions, depending on what the patient care

environment has to offer and what that resident needs to learn. Activities that are

flexible and multi-layered fare best in the unpredictable world of apprenticeship

education, where patients may not keep appointments, the attending may be too busy to

teach, or the computer may be down. Give residents options for self-directed enrichment

(e.g., readings, photo sets, cases, websites) to expand their learning and fill unexpected

down time.

Creative and innovative education helps to stimulate the weary veteran of many

years of training. Look for new combinations of old techniques (e.g., learning

competitions instead of paper tests), new approaches to exploring authentic learning

environments (e.g., visits to political venues where health policy is made, visits to

community resource sites), or novel ways to stimulate learner interest (e.g., online

treasure hunts, or drive-by community assessments). Getting residents involved in

3

designing their own educational experiences is a good way to create innovative

approaches—you may be the master of the content, but they know best what will

interest their peers and themselves.

Good planning. Careful planning gives a learning experience rigor and vigor, and makes it a

functional part of a pre-designed curriculum. This feature of sound learning experiences is so

important that we discuss it separately in the final segment of this tutorial.

4c. How to Plan a Competency-based Learning Experience (New or

Revised)

Key Steps to Planning a Learning Experience:

1. Find protected time to think and plan. Curriculum development is time consuming.

Before starting a planning project, large or small, carefully review the elements of the

program that are already in place. A strategic assessment of needs and opportunities helps

you to select where changes will be most likely to receive approval and support. Seek allies

among leaders and players, develop supportive resources as needed, and then follow a stepby-step plan to revise the program, as outlined below.

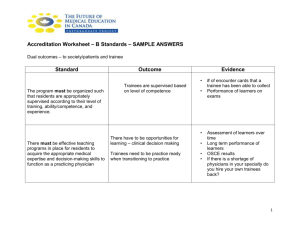

2. Determine the outcomes that you want to achieve, and then select your goals and

objectives. In the world of competency-based education, the first step is deciding exactly

what you want your learners to be able to do at the end of the educational program. In the

educational planning process, these selected outcomes drive the goals and objectives which

provide scaffolding for the curriculum. When you build a new learning experience around

goals and objectives, it is easier to keep it focused on a clear set of learner outcomes.

Teachers know what they should be teaching, residents understand what is expected of

them, and the evaluation process is fair and open.

Although you can download predesigned goals lists from the Educational Guidelines, you will

need to tailor these lists to your own educational setting. Since the lists were planned to be

fairly comprehensive, they nearly always need substantial shortening. The more focused you

can make the list, the more useful it will be for educational and evaluation planning.

3. Coordinate your work with the Program Director. Before, during and after you plan a

new educational experience, be sure to consult with your program director. Your teaching

and especially your evaluation activities need to be coordinated with the rest of the program.

4. Select learning activities. When choosing activities to help learners meet your goals for

them, consider activities that:

Avoid redundancy with existing experiences in the program.

Are rich in learning value for different kinds and levels of learners. (See 4b. Qualities of

Sound Learning Experiences.)

Efficiently use time and resources.

Address not only first-time learning, but also skill maintenance and reinforcement.

Combine education with evaluation opportunities.

As you make your selections, be sure to involve stakeholders in the educational process, such

as your colleagues, staff, ideally some patient advocate and, of course, the residents. This

provides buy-in and offers practical real-world suggestions.

5. Plan faculty roles. You are likely to need faculty cooperation in teaching, supervision,

coordination, and evaluation. Getting collaborators involved early will enhance your chances

4

of getting needed help later on, and input from others will probably improve your product.

When your new rotation or experience is ready to start, be sure to orient the faculty to their

responsibilities as teachers and evaluators.

6. Develop instructional materials. Although clinical activities always need supervision,

supplementary learning experiences (e.g., readings, case studies, demonstrations,

experiential activities in the community) can often be set up to run relatively independently,

if they have good instructions and documentation. To enhance efficiency, consider using

web-based methods that learners can access anytime and anywhere.

7. Develop a time plan. Think realistically about how much time your planned learning

activities will require—from residents, staff, and faculty. At this point, many educators realize

that they have planned too much to teach in the time available. One way to condense the

plan is to teach principles in 1-2 settings, and ask the residents to apply them to other

settings. Also consider that residents may have opportunities later in their training to add to

the skills you plan to teach. Think about how you might work with your colleagues to guide

continuing learning on this topic throughout the residency (e.g., via noon conferences, ward

and continuity experiences, journal clubs). Also, giving residents some independence in

choosing and managing their learning will reduce teaching time and help them develop skills

for life-long learning.

8. Develop evaluation tools and processes. To plan for evaluation, return to your list of

goals and objectives. (This may be a good time to abbreviate your list further.) Select those

objectives that are most important for evaluation. A targeted evaluation that focuses on a

few key learning tasks will be more efficient to administer and more effective in guiding

residents towards success in meeting performance requirements. You can also make

evaluation more efficient by finding ways to combine teaching with evaluation around

your key objectives. For example:

Create a checklist for conducting a focused patient history or exam that can provide

guidelines for residents and a structured feedback form for faculty.

Have residents conduct a chart review of a group of their recent clinical encounters

to assess a specific aspect of their patient care activities (e.g., timely communication

with families about lab results, patterns of antibiotic prescription), and discuss the

results with them.

9. Conduct faculty development. This is the critical last step before implementing a new

learning experience. Be sure that faculty understand their individual roles, and grasp the

larger picture: the purpose of the curriculum as a whole, its goals and objectives, the

outcomes expected of residents, and the evaluation methods which have been developed.

Orienting faculty to a new curriculum provides a good opportunity to broaden their thinking

about educational principles and processes.

10. Conduct periodic evaluation of the new educational activity. It is important to

evaluate the curricular change after a period of implementation, so that problems and

opportunities for further refinement can be identified, thus initiating a process for continuous

program improvement.

Source: Kittredge, D., Baldwin, C. D., Bar-on, M. E., Beach, P. S., Trimm, R. F. (Eds.). (2004). APA Educational

Guidelines for Pediatric Residency. Ambulatory Pediatric Association Website. Available online: www.ambpeds.org/egweb.

Project to develop this website was funded by the Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation 2002-2005. ©2004 Ambulatory Pediatrics

Association. All Rights Reserved.

5