PART 1 – PROJECT CONCEPT - Global Environment Facility

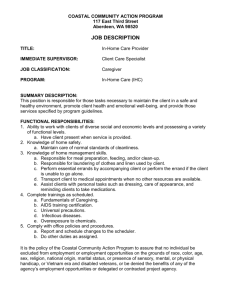

advertisement