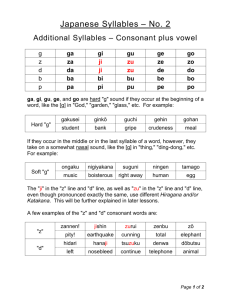

latin consonants

advertisement

Dragana RADOJEVIĆ (Università di Belgrado) RADDOPPIAMENTO FONOSINTATTICO IN ITALIAN: AN ASSIMILATORY PROCESS OR A RULE OF COMPENSATORY LENGTHENING? KEY WORDS: Raddoppiamento Fonosintattico, assimilatory process, compensatory lengthening. 1. INTRODUCTION There are different theories which try to explain Raddoppiamento Fonosintattico (RF), its origin, the reasons for which it occurs and the contexts in which it occurs. In this essay, I will firstly explain what RF is and where it usually occurs in Standard Italian. Secondly, I will mention when and by whom RF was discussed for the first time, and when and where it was attested for the first time. I will also discuss the question whether it existed in Latin and in Proto-Romance or not. Thirdly, I will explain the relationship between RF and gemination in relation to the parts of Italy in which it exists and those parts in which it does not exist. Then, I will provide a brief review of two hypotheses concerning RF. This review will be extended in the two following sections of the essay, where I will give a critical account of these hypotheses and assess their merits and deficiencies. The following section will deal with the occurrence of RF in central and southern varieties of Standard Italian. My conclusion will be that, although all the mentioned theories have contributed, to some extent, to the explanation of RF, only Loporcaro’s theory provides a thorough analysis of the origin of RF, its diachronic and synchronic aspects and the relationship between them. I will argue that most theories failed to explain RF because they tried to establish a general rule which would be valid for all the cases of RF in all the varieties. My suggestion will be that, since RF is not a general Italian phenomenon, but rather a phenomenon with different characteristics in different Italian varieties, we should not be looking for a general rule for RF, but for separate rules for each variety or group of similar varieties of Standard Italian, in which it occurs. 2. WHAT IS RF AND WHERE DOES IT OCCUR? Raddoppiamento Fonosintattico (RF) is an Italian phonological phenomenon, which consists in the lengthening of a word-initial consonant when preceded by a wordfinal stressed (or, more precisely, ‘not unstressed’) vowel. RF occurs after: (a) polysyllables stressed on the final vowel: i) città vecchia [tʃit'ta v'vɛkkja] ‘old city’; ii) cantò bene [kan'tɔ b'be:ne] ‘he sang well’; This essay was written during an MPhil course in Linguistics at the University of Cambridge in 1998-99. (b) stress-bearing (‘strong’) monosyllables: i) sta bene ['sta b'be:ne] ‘he is well’; ii) tè caldo ['te k'kaldo] ‘hot tea’; (c) some unstressable (‘weak’) monosyllables: i) a casa [a k'ka:sa] ‘to the house’; ii) e tu [e t'tu] ‘and you’; (d) some penultimate stressed polysyllables: i) come te ['ko:me t'te] ‘like you’; ii) qualche cosa ['kwalke k'ko:sa] ‘something’. 3. RF IN LATIN AND IN PROTO-ROMANCE RF was discussed for the first time in the XVI century by Claudio Tolomei, who wrote: S'io non m'inganno, questo raddoppiamento fu da noi prima scoperto e posto in luce (Fiorelli 1958: 122). This, of course, does not mean that RF had not existed before Tolomei, but judging by the documents found by now, no one before him had discussed it. RF is attested in one of the earliest documents of Italian, beginning with sao cco kelle terre…, in the “Formula testimoniale di Sessa” of March 963. This is a proof that RF is not a recent phenomenon, but still it is not attested in documents written in Latin. However, according to Hall (1964: 553), there was extensive assimilation, with resultant doubling of consonants, at morpheme boundaries in derivatives, especially those formed with prefixes that ended in consonants (e.g., ad + ferre > afferre ‘to bring to’, sub + pōnere > suppōnere ‘to place under’). He argues that it is reasonable to suppose that the same kind of assimilation took place in everyday speech, after ad, sub, etc., when used as prepositions, or after et, aut, sed, and similar conjunctions: e.g., et ‘and’ + dīxit ‘he said’ > *eddīxit, or ad ‘to’ + matrem ‘the mother’ > *ammatrem. He then concludes that, on the basis of these considerations, it is justified to argue that RF existed in Proto-Romance, both in derivation and between words in sentence. 4. RF IN ITALIAN 4.1 RF vs. gemination Nowadays, RF occurs in Standard Italian and in its varieties spoken south of La Spezia – Rimini line, whereas it does not occur in varieties spoken north of La Spezia – Rimini line. In fact, RF occurs in those varieties in which long consonants exist, and it does not occur in those varieties in which long consonants do not exist. Additionally, consonants which can undergo RF are the same consonants which can be reduplicated within a word, apart from /ʎ, ɲ, ts, dz, ʃ/, which are always long in intervocalic position. Therefore, gemination and RF are correlated phenomena and gemination should be taken into account when we investigate RF. However, their relationship can be interpreted in different ways, as well as the origin of RF and of geminates. We will see that almost all the authors who investigate RF take into account its relationship with gemination, but their explanations for their origin are different. 2 4.2 The origin of RF There are two hypotheses concerning the origin of RF: (1) RF originates exclusively as consonantal assimilation. Latin final consonants became assimilated to any following initial consonant, and then disappeared leaving a trace in the redoubling of this consonant. Any case of RF today determined by words whose historical antecedent did not end in a consonant, must be explained as analogical extension. (Loporcaro 1988: 374) (2) RF triggered by oxytones occurs as a consequence of the principle that all stressed syllables that occur within a phrase must be heavy (i.e., must contain either a long vowel, or a short vowel + consonant). RF is therefore viewed as a phonological ‘makeweight’ strategy, producing a heavy word-final stressed syllable, by projecting or extending into it the initial consonant of a following word. (Maiden 1995: 74) In the following sections I will firstly discuss the most important authors who opt for the second hypothesis and secondly those who opt for the first hypothesis. 5. RF - A RULE OF COMPENSATORY LENGTHENING? 5.1 Saltarelli Saltarelli (1970: 28-9) tries to explain the relationship between vocalic and consonant length by the notion of ‘duration rhythm’, which he expresses in the following way: (1) a long vowel is twice as long as a following consonant, and (2) double consonants are about twice as long as single consonants. He then extends this rule to RF, arguing that, in the continuous physical stream of speech, a word-final short vowel requires that the following non-vocalic segment(s) be twice its duration, in accordance with the ‘duration rhythm’. He also claims that, according to the ‘duration rhythm’, if vowel length is known, it is possible to predict consonant length, which is a radical change in relation to the Italian phonological tradition, which considers vowel length predictable on the basis of consonant length. He goes on to claim that, if vowel length is known, it is possible to predict not only consonant length, but also stress, by applying two rules: (1) if the penult is ‘light’ (which means: short vowel in open syllable), stress antepenult; otherwise stress penult; (2) single consonantal segments are long if the preceding vowel is short and stressed, and if they are also followed by a vocalic segment. According to Saltarelli, these rules are supposed to explain and predict RF, but we will see that they neither explain it nor predict it. Since the rule (1) does not assign stress to monosyllabic words, it cannot create an appropriate context for RF. For example, the rules would not predict the lengthening of the /k/ in a casa, because the preceding /a/ is not stressed. However, opinions differ on whether prepositions are stressed or not. Lepschy (1973: 110-1) criticises Saltarelli’s theory built on the contrast ['a k'kasa] vs. [la 'kasa] (it is very interesting that in Saltarelli’s example the preposition a in a casa is stressed although he does not even mention monosyllabic words 3 in his rules concerning stress), by insisting on the fact that, although Saltarelli rightly notices that a causes RF, whereas la does not, they are both unstressed, whereas in Saltarelli’s example a is stressed. On the other hand, Vogel (1982: 42) is not so rigorous in her criticism. She leaves the question whether prepositions should be stressed or not open, saying that, according to The Sound Pattern of English (Chomsky and Halle, 1968), they would not be considered as stressed, but according to Jackendoff’s X-bar Syntax (1977), stress should be assigned to prepositions as well. Di Pietro (1971: 726) suggests that Saltarelli’s example a casa should be contrasted not with la casa, but with di casa [di 'ka:sa] ‘of the house’, because it does not seem likely that di and a, since they are both prepositions, would have different levels of stress. The historical explanation is that the preposition a was once ad (and still is before vowels, as in ad esempio ‘for example’) and the result is an assimilation to a following consonant, while di never ended in a consonant (the forms dello, della, etc., in which the preposition occurs with the definite article, derive their consonant length from the Latin demonstratives and not from the preposition, e.g. DE + ILLUM > dello, etc.). Loporcaro (1997: 42) places monosyllabic prepositions among unstressable, so-called ‘weak’ monosyllables. In addition, if we look at the opposition e vs. è, we can see that both of them trigger RF, but only è is stressed (or more precisely, it is a stress-bearing ‘strong’ monosyllable), whereas e is unstressed. We can conclude that prepositions are not stressed. Therefore, Saltarelli’s theory, based on the false assumption that consonant length and stress are predictable only on the basis of vowel length, fails to predict consonant length and stress within a word and across word boundaries, i.e. it fails to predict and explain RF. Vogel (1982: 48) tries to save Saltarelli’s rule (1) by adding the third possibility, which is that stress is assigned to the last vowel if neither the first part nor the second part of the rule (1) can apply. In that case the derivation of a casa is correct, but then the rule predicts RF in la casa as well, because a in la is also the last vowel like the preposition a in a casa. There is another aspect in which Saltarelli’s theory is radical in relation to the Italian phonological tradition. He applies his rules to detto, by deriving it from /dek+t+o/ not through assimilation, but through the fall of the /k/ (/dek+t+o/ > /de+t+o/), and the lengthening of the /t/ after a short stressed vowel (/de+t+o/ > /de+tt+o/) (Saltarelli 1970: 86). Since the same rules are supposed to apply to RF, the question is would the explanation for [a k'kasa] be that it derived from [ad 'kasam] through the fall of the /d/, and the lengthening of the /k/ after a short stressed vowel? Perhaps this theory seems to be very problematic because it is based on another problematic theory. Namely, Saltarelli bases his theory on Porena’s explanation for double consonants and their origin. Porena (1942: 93) argues that double consonants are lengthening of simple consonants, and that the origin of lengthening in Latin and in Italian is the compensation for the loss of a consonant by strengthening the remaining one in the group. The following changes: FACTUS > fatto, RAPTUS > ratto, IPSUM > esso, AD ROMAM > a Rroma, are explained as the loss of C, P, D, and the lengthening of the remaining consonant to preserve the length of the syllable. Thus, we can conclude that this theory of Saltarelli’s, based on Porena’s problematic explanation, seems to be very superficial and poorly argued, and therefore it fails to explain the origin of geminates and of RF in Italian. 4 5.2 Vogel Vogel (1978: 20-4) suggests that RF may be explained by constraints on the phonological structure of Italian words, specifically the constraints on the distribution of vowel length and syllable structure. She claims that, if we know whether the vowel in question is stressed or unstressed and whether it is in an open or closed syllable, it is possible to predict the length of the vowel, because vowels in non-final, stressed, open syllables are long, and all other vowels are short. On the basis of this claim she argues that a well-formed word in Italian must conform to her Well-Formedness Condition: Vowels in non-final stressed open syllables are [+long]; all other vowels are [-long]. Since, according to Pulgram (1970), in connected speech the boundaries between words are often erased, resulting in larger phonological units, Vogel concludes that these large units are then subject to the same criteria of well-formedness as individual words. In isolation, the –o of parlo ‘I speak’ and the –ò of parlò ‘he spoke’ are both short since they are in final position. In connected speech, however, they are no longer final vowels, but medial in the phrases, such as: parlo bene and parlò bene. While ['parlo 'be:ne] (parlo bene) is well-formed, *[par'lɔ 'be:ne] (parlò bene) is not, because the short -ò- is in a stressed, internal, open syllable, which is the environment for long vowels. Therefore, something must change in order to make the second form conform to WFC. She suggests that we should analyse parlò bene as in (1). (1) parl o + stress – long S1 bene S2 The form in (1) conforms to the WFC since the short, stressed, non-final vowel is no longer in an open syllable, but in a closed syllable ending with b, which is now simultaneously a member of two adjacent syllables. The ambisyllabic b in parlò bene is therefore produced as a long consonant. Thus, she concludes that RF operates in Italian to join the initial consonant of word2 to the end of word1, in order to make sequences of words in connected speech conform to the well-formedness conditions on words of the language. Vogel’s theory cannot account for the cases in (d). According to WFC, the phrases come te and qualche cosa should be well-formed because e in isolated words come and qualche is a short final unstressed vowel, and in the phrases in question it is a short vowel in an unstressed, internal, open syllable. Thus, it should not trigger RF, but it does. The same objection can apply to the cases in (c) if we agree with the claim that prepositions are unstressed. We have demonstrated that, although Vogel’s theory accounts for the cases in (a) and (b), it does not account for the cases in (c) and (d). Therefore, we can conclude that it fails to explain and predict RF. 5 5.3 Vincent Vincent (1988: 421-31) tries to answer the question: “Why does the initial consonant of a following word become lengthened when a lengthening of the final vowel would have done just as well to eliminate the structural anomaly of short vowel in a stressed open syllable?” (ibid.: 430) He argues that a short vowel is always lengthened if it occurs in an open syllable which bears penultimate stress, and if a short vowel occurs in an open syllable bearing final stress, the initial consonant of the following word is always lengthened. Consonant lengthening also applies in proparoxytones. His diachronic answer to the above question is that “vowel lengthening was not an option that was available for anything but penultimate syllables, where it represents a residue of a Latin prosodic effect assigning prominence to that syllable. In other contexts the default development was consonant lengthening, as witnessed in both antepenultimate and final positions” (ibid.). However, he cites a number of proparoxytones in which the vowel has not been lengthened, which is attested by the absence of the diphthongs /jɛ, wɔ/ which are the usual reflexes of Latin /ĕ, ŏ/: pecora ['pe:kora] ‘sheep’, medico ['me:diko] ‘doctor’ (on the other hand, in many Italian dialects we find ['pjɛkora] and ['mjɛdiku]). It should also be noticed that these words have a long stressed vowel in antepenultimate syllable, and not a long consonant preceded by a short stressed vowel, as in macchina ['makkina] ‘car’, femmina ['femmina] ‘woman’. Long consonants in these words were originally short. An additional objection to Vincent’s theory could be the cases of consonant lengthening in paroxytones: tutto ‘all’ < TOTU(M), succo ‘juice’ < SUCU(M). Vincent’s theory tries to explain RF by correlating it with the process of internal gemination, but it does not seem to be very convincing because it has many exceptions. Since we have seen that it fails to account for many cases of internal gemination, we can conclude that it also fails to account for the cases of RF, especially those in (c) and (d). 6. RF – AN ASSIMILATORY PROCESS? 6.1 Fiorelli and Camilli Fiorelli (1958: 122) and Camilli (1971: 133-4) adopt the explanation given in Dizionario enciclopedico italiano, vol. X, p. 71 (from Camilli ibid.: 134), which says that there are three historical reasons for RF: (1) Latin word-final occlusives are lost, but in the cases in which they were final in proclitics, within the same syntactic phrase, they left the same trace as within a word, for example: a me [a m'me] < AD ME; ammettere [am'mettere] < ADMITTERE. (2) The assimilation of a lost word-final consonant to a following word-initial consonant extended, by analogy, to other cases in which a different result would be expected, for example: tre cani ['tre k'ka:ni] < TRES CANES, compared with nasco < NASCOR (Tekavčić (1980: 235) provides similar examples: TRES CAPRAE > tre ccapre compared with nasco, and JAM PASSATUS > già ppassato compared with campo). 6 (3) The doubling of a word-initial consonant extended to all the cases in which a preceding word-final vowel was stressed, whatever its origin. The example tre cani in (2) does not seem to be very likely because the comparison with nasco is not adequate. Loporcaro (1988: 346) claims that, although it is true that s-first clusters never assimilate internally, a greater incidence of assimilation at word boundary is not at all unprecedented (he proves this claim with several examples from central and southern Italian dialects). Therefore, it seems more likely to argue that RF occurs in tre cani not because of an unexpected assimilation from TRES CANES, but rather because tre, after the loss of the final –S, triggers RF like any other stress-bearing ‘strong’ monosyllable. This claim needs further explanation. In my opinion, Fiorelli and Camilli are in the right when they argue that the original assimilation of a lost word-final consonant extended, by analogy, to other cases. However, it would be more adequate to claim that there were two types of analogy: (i) RF caused by the assimilation as in STAT BENE > sta bene ['sta b'bene] extended, by analogy, to cases such as sto bene ['sto b'bene] < STŌ BENE (there was no word-final consonant which could have been assimilated); (ii) RF extended, by analogy again, to all the cases in which a preceding word-final vowel was stressed, whatever its origin, e.g. tre cani ['tre k'ka:ni], té caldo ['te k'kaldo]. Therefore, tre cani should be given as example in (3) and not in (2) as in Fiorelli’s and Camilli’s explanation, and sto bene could be an example for (2). In conclusion, we can say that Fiorelli’s and Camilli’s thorough analysis of all the cases in which RF occurs and all the cases in which it does not occur gives us a very good explanation of RF. However, it fails to provide a complete explanation of the two types of analogy, through which the assimilation of a lost word-final consonant extended to all the cases in which a preceding word-final vowel was stressed. 6.2 Lepschy and Lepschy Lepschy and Lepschy (1977: 66) argue that there are two reasons for RF: 1. synchronic: final stressed vowels are short, but syllabic structure does not admit stressed short vowels followed by single consonants (V̆Č); of the two possible structures, V̆C̄ and V̄Č, the former is selected in the case of RF. This reason applies to all the cases of RF. 2. diachronic: RF represents the assimilation of a word-final Latin consonant (e < ĔT, a < ĂD, o < AUT, etc.) to the following word-initial consonant. This reason applies only to the cases in (c) and (d). This explanation seems to be rather simple and superficial. It accounts for all the cases of RF, but it does not explain the relationship between the diachronic and synchronic reasons, so that it seems that there are two types of RF which have nothing in common. That, of course, is not correct. Thus, this analysis fails to give us a thorough explanation of the origin of RF because it does not even mention the analogy, which could be represented as a connection between the diachronic and synchronic reasons. 7 6.3 Canepari Canepari (1986: 27) argues that the same principles which applied to ADMĬTTO > ammetto, LACTE(M) > latte, CAPSA(M) > cassa, applied also to AD MĒ > a mme, TRĒS CAPRAE > tre ccapre, IAM PASSATU(S) > già ppassato, and subsequently to CIUITATE(M) > *cittade > città. This principle, then, extended, by analogy, to all oxytones, whatever their origin, and to ‘strong’ monosyllables. This explanation of RF, apart from the problematic interpretation of RF in tre capre already mentioned in section 6.1, accounts for all the cases of RF, but it fails to take into account the analogy by which RF in sta bene < STAT BENE extended to sto bene < STŌ BENE. Therefore, although it accounts for all the cases of RF, it does not provide a satisfactory and complete explanation for the origin of RF. 6.4 Loporcaro Loporcaro (1997: 42) claims that RF in (a) and (b) is phonologically regular, because it is determined by a lexical (primary) stress on the final vowel of w1. He then argues that any word that meets this condition triggers RF, whatever the syntactic context: tè [nn]ero ‘black tea’, ho preso il tè [nn]el soggiorno ‘I had tea in the lounge’. He admits that one can argue that strong monosyllables, such as imperatives sta’, fa’, da’ va’ (e.g., sta’ [f]ermo ‘stand still’, va’ [v]ia ‘go away’), are exceptions to this generalisation, but he says that they are only seeming exceptions, because they derive from stai, fai, dai, vai. However, it is not clear if he allows the interpretation va’ [vv]ia or not. On the other hand, Camilli (1971: 136-40) and Lepschy and Lepschy (1977: 67) claim that da’, di’, fa’, sta’, va’ do not cause RF because they are weak monosyllables derived from dai, dii (dici), fai, stai, vai, but dà, dì, fa, sta, va cause it because they are strong monosyllables. Therefore, they interpret [va v'via] as ‘he goes away’ or ‘go away!’, and [va 'via] only as ‘go away!’. As far as RF in (c) and (d) is concerned, Loporcaro (1997: 42) argues that it does not reflect any synchronic phonological regularity, because no synchronic phonological feature captures all and only the words in (c) and (d), or group them with (a) and (b). Therefore, he suggests that each of the words in (c) and (d) should be lexically specified as triggering RF. He also suggests that RF in these words should be analysed diachronically because they all derive from Latin words ending in a consonant, which assimilated in external sandhi: e.g., ET DICIS > e [dd]ici ‘and you say’, *QUOMODO+ET ME > come [mm]e ‘like me’. Loporcaro (1988: 346-7; 1997: 42) explains the origin of RF as follows: RF began as a sandhi consonantal assimilation (SCA), and only subsequently extended to all stressbearing ‘strong’ monosyllables, even if they did not derive from the loss of the word-final consonant, e.g., me, te, sé, tu, se, dò, sto, so, ho, etc. He gives the example of ho fatto ['ɔ f'fatto] ‘I have done’, which derives from HA(BE)O FACTU(M), where no etymological consonant was present. RF in this case is explained by the example of RF from pre-literary Italian, where it occurred only in ha fatto ['a f'fatto] ‘he has done’, which derived from HA(BE)T FACTU(M) (in this case an etymological consonant was present). The same goes for polysyllabic oxytones like cantò, finì, correrà, città, etc., after which today’s Standard Italian has a productive rule of RF, which applies to loanwords or neologisms with the 8 same phonological structure. He says that in this case, as Rohlfs (1966: 235-6) points out, we are dealing with a secondary analogical extension of an originally consonantal assimilation, concerning the final consonant of polysyllables: CANTAUT MALE > *[kan'tau̯ m'male] > [kan'tɔ m'male], *CITTAT(E) BELLA > [tʃit'ta b'bɛlla]. Loporcaro’s conclusion is that “due to frequent co-occurrence of final stress with final (assimilated) consonants and to the disappearance of final consonants in other phonosyntactic contexts, final stress was ascribed strengthening effect through abduction”. The reason of such an extension is that at a certain point a reinterpretation of the rule occurred, after which RF was perceived as dependent on the stress pattern of the triggering word. He then extends his argument by saying that a close relationship between SCA and RF occurs synchronically as well. Namely, any SCA may turn into RF once the final consonant is deleted underlyingly via restructuring. Loporcaro’s theory takes into account both diachronic and synchronic aspects of RF, and it correlates them in the most appropriate way. In addition, it accounts successfully for all the cases of RF. In my opinion, this is the only theory which provides the most thorough and the most plausible explanation of the origin of RF. 7. RF IN CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN VARIETIES OF STANDARD ITALIAN RF occurs in varieties of Standard Italian spoken South of La Spezia – Rimini line, i.e. it occurs in central and southern varieties, whereas it does not occur in varieties spoken North of La Spezia – Rimini line, which are called northern varieties. On the basis of this fact, one could assume that the same words trigger it in all central and southern varieties, and that it always occurs in the same contexts in all these varieties. However, this is not the case. Different words trigger or do not trigger RF in different central and southern varieties. For example, varieties spoken in Rome and in Florence differ in several cases: a) da, dove, and interrogative come do not usually cause RF in Rome, whereas in Florence they do; b) ah, deh, eh, oh, o, trigger RF in Rome, but not in Florence; c) the articles lo, la, li, le, are usually subject to RF in Florence, but not in Rome (while l’ tends to be lengthened when followed by a stressed vowel); d) ne and non are usually subject to RF in Florence, but not in Rome; e) the initial consonants of là, lì, così, più, qua, qui, chiesa, sedia, merda, tend to be lengthened in Rome, but not in Florence (De Mauro 1984: 391). The situation in some parts of Umbria and the Marche is very similar. Generally speaking, in the south, RF is not triggered by a preceding word-final stressed vowel (whereas in Tuscan varieties it is), and by: ha, chi, da, o, sta, tra, va (ibid.: 397). In Abruzzo, RF often fails to occur after polysyllables ending in a stressed vowel, and after some monosyllables such as dà ‘he gives’ (and some other third person singular verb forms), da, già, giù, dove, come, qua, chi, while it is triggered by mentre, sempre, ogni. The situation is similar in most parts of southern Italy and in Sicily. In some parts of Basilicata, Sardinia, and Calabria, traces of the Latin third person singular inflection -T are preserved, and the result is that, in these varieties, third person singular verb may trigger RF, e.g., bisogna partire [bi'soɲɲa ppar'ti:re] ‘it is necessary to leave’. (Maiden 1995: 256) Telmon (1993: 108-16) provides several interesting examples of RF triggered by the article la: a) in Sardinia: la barca [la b'barka], la roccia [la r'rottʃa]; b) in Sicily: la gola 9 [la g'gɔ:la]; c) in the south-east Umbria, in the Marche, in Lazio, Campania, Puglia, Abruzzo, Molise, Sardinia: la fame [la f'fa:me]. 8. CONCLUSION All the theories discussed in sections 5 and 6 have contributed to some extent, to the explanation of RF. We have proved that the theories which interpret RF as a rule of compensatory lengthening have many deficiencies, and that they fail to explain its origin and to predict its occurrence. On the other hand, the theories which interpret RF as an assimilatory process have many merits. They account for all the cases of RF and explain both diachronic and synchronic reasons for RF. However, most of them fail to provide an explanation for the relationship between the diachronic and synchronic aspects of the problem, and the two types of analogy which intervened. The only exception is Loporcaro’s theory, which seems to be the most thorough and plausible one, because it explains the origin of RF, the diachronic and synchronic aspects of it and the relationship between them. It provides an appropriate analysis of the two types of analogy which correlate the diachronic and synchronic aspects of the problem, and it accounts successfully for all the cases of RF. However, none of these theories allows us to predict for sure where RF will and where it will not occur, nor does any of them explain why RF exists in certain cases in some varieties of Italian, and in other cases in other varieties. In section 7 we have seen that the cases in which RF occurs and in which it does not occur differ in relation to which central or southern Italian variety we are dealing with. On the basis of evidence from section 7, we can conclude that RF is not a general Italian phenomenon, but rather a phenomenon with different characteristics in different Italian varieties. Regional pronunciations are influenced by the phonological systems of the dialects spoken in these regions. Since we would not expect to propose one general rule which would account for all the cases of any other phonological phenomenon in all the dialects, why should we expect to find a general rule which would account for all the cases of RF in all the varieties? Similarly, if we know that we cannot formulate, for example, one general syntactic rule for subordination or mood choice in different dialects, why should we expect RF to be so uniform? Most theories tried to establish a general rule which would be valid for all the cases of RF in all the varieties. Maybe the reason why they failed to explain RF was that they all started from the wrong premise that RF was a uniform phenomenon and that, therefore, it needed a uniform treatment. We have proved that, since RF is not a uniform phenomenon, it is impossible to establish a general rule without a number of exceptions. We can conclude that a practice of many authors, who try to find a general rule for RF, is mistaken, because RF is a complex phenomenon, differently expressed in different Italian varieties, and, therefore, it must be treated differently. In conclusion, I suggest that we should not be looking for a general rule for RF, but rather for separate rules for every variety, or better, for every group of similar varieties of Standard Italian. Of course, some of these rules will apply to all the cases of RF in all the varieties, but the other rules will be specific for every variety or group of similar varieties. Maybe then, RF will not seem so unresolvable as it seems today. 10 References Camilli, Amerindo (1971) Pronuncia e grafia dell’italiano. Firenze: Sansoni. Canepari, Luciano (1986) Italiano standard e pronunce regionali. Padova: CLEUP. De Mauro, Tullio (1984) Storia linguistica dell’Italia unita. Bari: Laterza. Di Pietro, Robert J. (1971) Review of Saltarelli, M. (1970), A Phonology of Italian in a Generative Grammar. The Hague: Mouton. Language 47: 718-30. Fiorelli, Piero (1958) Del raddoppiamento da parola a parola. Lingua nostra 19: 122-127. Hall, Robert A. (1964) Initial Consonants and Syntactic Doubling in West Romance. Language 40: 551-556. Lepschy, Giulio (1973) Review of Saltarelli, M. (1970), A Phonology of Italian in a Generative Grammar. The Hague: Mouton. Linguistics 109: 109-13. Lepschy, Anna Laura and Lepschy, Giulio (1977) The Italian Language Today. London: Hutchinson. Loporcaro, Michele (1988) History and geography of raddoppiamento fonosintattico: remarks on the evolution of a phonological rule. In P. Bertinetto (ed.), Certamen Phonologicum, pp. 341-87. Loporcaro, Michele (1997) Lengthening and raddoppiamento fonosintattico. In M. Maiden and M. Parry (eds), The Dialects of Italy. London and New York: Routledge. Maiden, Martin (1995) A Linguistic History of Italian. London and New York: Longman. Napoli, Donna Jo and Nespor Marina (1979) The Syntax of Word-initial Consonant Gemination in Italian. Journal of the Linguistic Society of America 55: 812-841. Porena, Manfredi (1942) Per una piu’ esatta descrizione dei suoni consonantici italiani. Lingua nostra 4: 91-94. Rohlfs, Gerhard (1966) Grammatica storica della lingua italiana e dei suoi dialetti. I Fonetica. Torino: Einaudi. Saltarelli, Mario (1970) A Phonology of Italian in a Generative Grammar. The Hague, Paris: Mouton. Tekavčić, Pavao (1980) Grammatica storica dell’italiano. I Fonematica. Bologna: Mulino. Telmon, Tullio (1993) Varietà regionali. In A. Sobrero (ed.) Introduzione all’italiano contemporaneo. La variazione e gli usi. Bari: Laterza. Vincent, Nigel (1988) Non-linear Phonology in Diachronic Perspective: Stress and Wordstructure in Latin and Italian. In P. Bertinetto (ed.), Certamen Phonologicum, pp. 421-32. Vogel, Irene (1978) Raddoppiamento as a Resyllabification Rule. Journal of Italian Linguistics 3: 15-28. Vogel, Irene (1982) La sillaba come unità fonologica. Bologna: Zanichelli. 11 Dragana Radojević FONOSINTAKSIČKA REDUPLIKACIJA U ITALIJANSKOM: ASIMILATORNI PROCES ILI PRAVILO O KOMPENZACIONOM PRODUŽAVANJU? (Rezime) Ovaj rad predstavlja kritički osvrt na najvažnije teorije o fonosintaksičkoj reduplikaciji u italijanskom jeziku zasnovane na dvema najzastupljenijim hipotezama o ovom fenomenu. Teorije koje polaze od hipoteze da je reč o kompenzacionom produžavanju početnog konsonanta reči kojoj prethodi reč s naglašenim finalnim vokalom, koji je uvek kratak, radi zadovoljavanja principa da svi naglašeni slogovi unutar rečenice moraju imati ili dug vokal ili kratak vokal i konsonant, ne uspevaju da na zadovoljavajući način objasne ovaj fenomen. S druge strane, teorije zasnovane na hipotezi da je fonosintaksička reduplikacija rezultat procesa asimilacije izgubljenih latinskih finalnih konsonanata s početnim konsonantom sledeće reči, a da se po analogiji s njima javlja i kod reči koje su se u latinskom završavale vokalom, vrlo uspešno objašnjavaju ovaj fenomen. Međutim, nijedna od navedenih teorija ne može sa sigurnošću da predvidi u kojim će slučajevima doći do fonosintaksičke reduplikacije, a u kojim neće, niti uspeva da objasni zašto se ona javlja u određenim slučajevima u nekim italijanskim varijetetima, a u drugačijim slučajevima u drugim varijetetima. Budući da ima različite karakteristike u različitim italijanskim varijetetima, nastale pod uticajem dijalekata određenih regija, fonosintaksička reduplikacija, dakle, nije opšti italijanski fenomen. Upravo zbog toga što polaze od pogrešne pretpostavke da za fonosintaksičku reduplikaciju važe ista pravila u svim italijanskim varijetetima, navedene teorije ne nude sveobuhvatno objašnjenje ovog fenomena. Buduća istraživanja ovog fenomena, stoga, treba da uzmu u obzir njegove različite karakteristike u regionalnim varijetetima i utvrde posebna pravila za njegovo javljanje u svakom pojedinačnom varijetetu ili bar u grupama srodnih varijeteta. 12