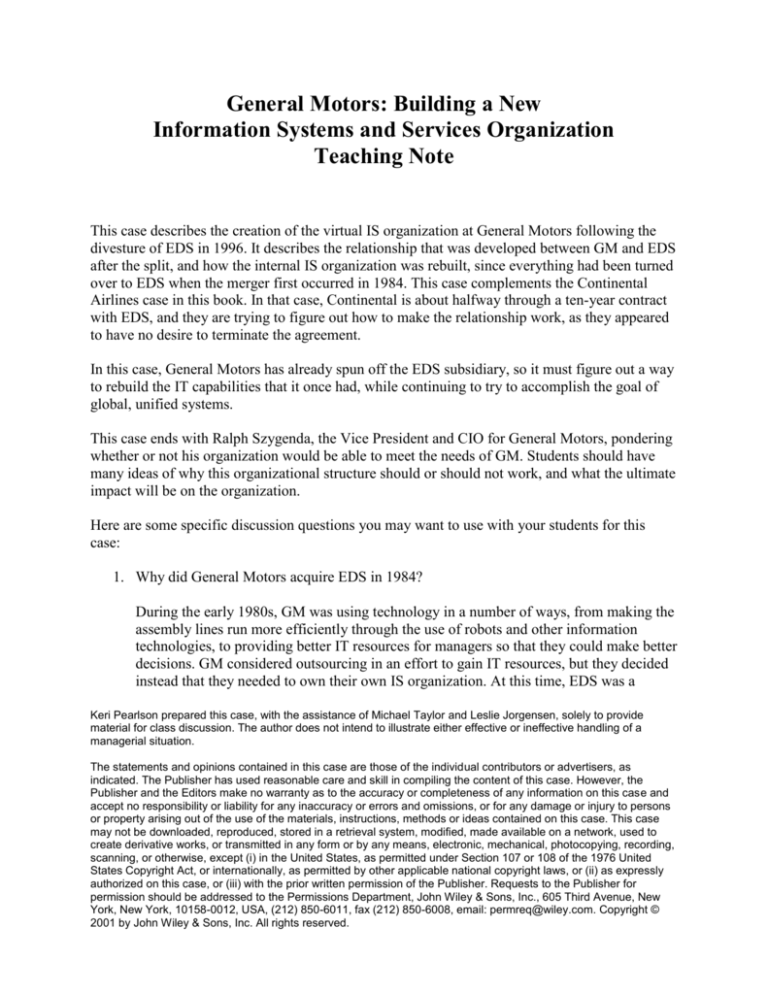

General Motors: Building a New

Information Systems and Services Organization

Teaching Note

This case describes the creation of the virtual IS organization at General Motors following the

divesture of EDS in 1996. It describes the relationship that was developed between GM and EDS

after the split, and how the internal IS organization was rebuilt, since everything had been turned

over to EDS when the merger first occurred in 1984. This case complements the Continental

Airlines case in this book. In that case, Continental is about halfway through a ten-year contract

with EDS, and they are trying to figure out how to make the relationship work, as they appeared

to have no desire to terminate the agreement.

In this case, General Motors has already spun off the EDS subsidiary, so it must figure out a way

to rebuild the IT capabilities that it once had, while continuing to try to accomplish the goal of

global, unified systems.

This case ends with Ralph Szygenda, the Vice President and CIO for General Motors, pondering

whether or not his organization would be able to meet the needs of GM. Students should have

many ideas of why this organizational structure should or should not work, and what the ultimate

impact will be on the organization.

Here are some specific discussion questions you may want to use with your students for this

case:

1. Why did General Motors acquire EDS in 1984?

During the early 1980s, GM was using technology in a number of ways, from making the

assembly lines run more efficiently through the use of robots and other information

technologies, to providing better IT resources for managers so that they could make better

decisions. GM considered outsourcing in an effort to gain IT resources, but they decided

instead that they needed to own their own IS organization. At this time, EDS was a

Keri Pearlson prepared this case, with the assistance of Michael Taylor and Leslie Jorgensen, solely to provide

material for class discussion. The author does not intend to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a

managerial situation.

The statements and opinions contained in this case are those of the individual contributors or advertisers, as

indicated. The Publisher has used reasonable care and skill in compiling the content of this case. However, the

Publisher and the Editors make no warranty as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this case and

accept no responsibility or liability for any inaccuracy or errors and omissions, or for any damage or injury to persons

or property arising out of the use of the materials, instructions, methods or ideas contained on this case. This case

may not be downloaded, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, modified, made available on a network, used to

create derivative works, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording,

scanning, or otherwise, except (i) in the United States, as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United

States Copyright Act, or internationally, as permitted by other applicable national copyright laws, or (ii) as expressly

authorized on this case, or (iii) with the prior written permission of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher for

permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 605 Third Avenue, New

York, New York, 10158-0012, USA, (212) 850-6011, fax (212) 850-6008, email: permreq@wiley.com. Copyright ©

2001 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

leading outsourcing provider of IT services – with expertise in state-of-the-art IT

resources.

2. Why did General Motors spin off EDS as a separate company in 1995?

There were many factors in the spin off of EDS in 1995. EDS had continued to operate as

a separate business, providing IT outsourcing for a number of firms. However, EDS

found it difficult to compete for contracts with firms that competed with one or more of

the business lines of GM. The case specifically noted the fact that EDS lost out on

bidding for two contracts – British Aerospace and Lucas Industries – because they

competed with GM and its Hughes Aircraft subsidiary.

Another factor was the fact that while EDS did do much good for GM, they were not

successful in all areas. The case pointed out that one of the primary goals of the

acquisition was for EDS to help with the integration of disparate computer systems across

GM’s units. This did not happen, nor could it under EDS’s direction. This required

consensus and direction from within GM.

Finally, IT had become so important to GM that the leadership felt that they needed the

IT expertise to be in-house in order to be as responsive as possible to the needs of GM

and its various business units.

3. Are there types of organizational problems that an outsource provider cannot address in a

firm?

EDS had problems addressing fragmentation of systems across divisions. As outsiders,

they did not have the power to bring the various internal groups together to reach the

consensus necessary to solve the problems that GM was facing. Thus, EDS or other

outsourcing providers would face significant problems with the internal political

struggles in a firm, as there is nothing that they can do to directly address those problems.

Of course, many outsourcing firms provide consulting services that are designed to help

address these types of political struggles in firms. However, this is not the strongest

capability of EDS.

4. Why was it so difficult for GM to accomplish its goal of common integrated worldwide

systems with EDS? Will they continue to face those same obstacles now that they are

running their own IT department again?

General Motors is a very large, complex world-wide organization, with each business

unit having its own goals and facing its own problems. As noted above, EDS faced

problems when trying to address the fragmentation of systems across divisions because of

the political realities in the firm. Once EDS was spun off, Szygenda had an information

officer in each sector and major business unit. Each of these information officers had dual

reporting relationships – to Szygenda and to the head of the business unit or sector. Thus,

it was somewhat in the best interest of each of the information officers to try to maximize

General Motors IS&S Teaching Note

Page 2

the benefits of IT for their particular business unit or sector, rather than for the firm as a

whole.

5. How effective is a matrix organization like the one that Szygenda is building at GM? Are

there any particular advantages or disadvantages of the matrix organization?

Szygenda needed 300 CIOs, information executives, and technologists to make his matrix

organization work. Each of these individuals would report to Szygenda as well as to

someone in their business unit (e.g., the head of the business unit or sector). This has the

advantage that there are key IT decision makers in each of the business areas that can

provide input to Szygenda, and who should be champions for IT changes and innovations

in their particular areas. Furthermore, the IT employees in each of these business units be

catalysts for change within their business unit, and yet be able to help with the crossorganizational problems that EDS faced during their time as a GM subsidiary.

There are also disadvantages, however. Each of the 300 IT employees would have

conflicting allegiances – to the central IT function and to their particular business unit or

sector. What was good for one was not necessarily good for the other. By being located in

the business unit, they were removed from the central IT function, and thus required

frequent meetings to help assure that they were up-to-date on company-wide plans and

goals.

General Motors IS&S Teaching Note

Page 3