Safety through Physical Enhancements and Neighborhood

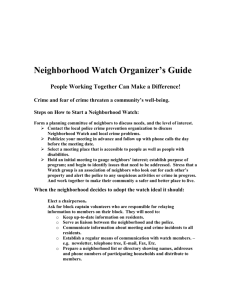

advertisement