5 - Teaching Heritage

environmental scientist’s perspective on Mutawintji National Park

NSW Department of Education and Training Sites and Scenes 1999

Mutawintji National Park, located in the Bynguano Ranges north-west of Broken Hill, is recognised internationally as an exceptionally preserved arid zone environment.

This area is significant because it contains unique geological features including rockholes and stratified rock surfaces. In addition, Mutawintji National Park supports numerous examples of rare and endangered flora and fauna, which are distinctive because they have evolved in isolation.

Flora and fauna

Mutawintji National Park, classified as an arid zone, is typical of the range and basin topography of western New South Wales. Mutawintji supports a wide variety of vegetation, including thirty endangered species. All native flora in Australian National

Parks are protected; however native flora in Mutawintji National Park are under threat, particularly from visitors and from introduced animals, such as livestock and feral goats. Thirty endangered plant species recently discovered by botanists were located in the rocky outcrops that are inaccessible to livestock and people.

Mutawintji National Park is home to a diverse array of animals that have adapted to the climate and landscape of the desert. Mammals, marsupials, birds and reptiles have adapted to Mutawintji’s hot climate and hilly landscape with special diets, and with heat-resistant coverings of skin or fur. Animals including emus, geckos, the euros and yellow-footed rock wallabies tend to concentrate around the rockholes, which provide them with shelter and water. After the rain season, the rockholes hold a regular water supply that lasts for many months. Without this supply, the nearest fresh water is at the Darling River, over 70 km away.

Geology

Mutawintji National Park has been identified as having strong geological and palaeontologic importance. However; the increasing numbers of animals and people in the area are degrading rock-formations and fossil deposits.

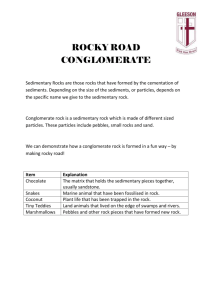

Millions of years ago, the red desert plains and hills of Mutawintji National Park were part of a seabed that covered most of inland Australia. Over time, sand and particles at the bottom of this inland sea compacted to become rock known as sediment rock or sandstone. Evidence of this watery past is found in the Bynguano Ranges, which are composed of sedimentary rock, interspersed with conglomerate rock, quartz and shale.

The Bynguano Ranges contain one of the few deposits of Cambrian fossils deposits in

Australia, which are estimated to be 300 to 500 million years old. As sediment and particles from the bottom of the sea compacted and became sedimentary rock, fish, shells and animals were trapped inside the rocks and became fossilised.

The unusual tiled landscape of the Bynguano Ranges with its fissures, cracks and rock overhangs, has been formed over millions of years owing to the natural process of erosion. Extreme weather conditions, including heat, frost and flash flooding, have worn down sedimentary and conglomerate rocks over the millenniums to create

bizarre rock formations. Rock overhangs and caves, which often house rockart, developed through the wearing away of soft sandstone overlaying conglomerate.

Rock-holes, another unusual feature of the Bynguano Ranges, were created by swirling torrents of water gouging out circular holes like wells into the rock surfaces.

Conclusion and recommendations

The NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service gazetted Mutawintji historic site as a nature reserve in 1967. Legislation passed by the NPWS seven years later, in 1974, meant that the natural environment and Aboriginal sites were protected. Since this time, however, Mutawintji National Park, which includes the historic site, has been under threat from degradation caused by a combination of natural processes and expanding visitor pressures.

Despite efforts taken to minimise rock erosion and to protect native animals and plants, visitor numbers to the area are climbing and introduced animals are not being controlled properly. We recommend that the NPWS prepare a more detailed environmental conservation plan for Mutawintji National Park, which would see tourist numbers limited and more effective control of introduced species enforced.