THE CHALLENGE OF CRITICAL THEORY FOR THOSE IN

advertisement

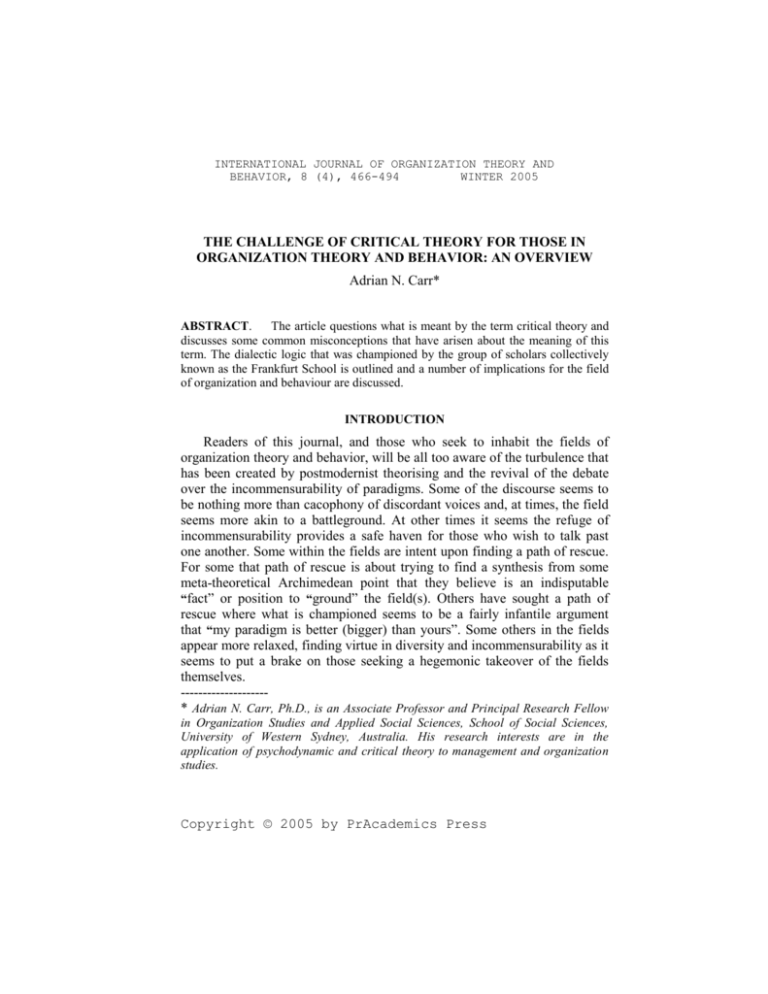

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ORGANIZATION THEORY AND BEHAVIOR, 8 (4), 466-494 WINTER 2005 THE CHALLENGE OF CRITICAL THEORY FOR THOSE IN ORGANIZATION THEORY AND BEHAVIOR: AN OVERVIEW Adrian N. Carr* ABSTRACT. The article questions what is meant by the term critical theory and discusses some common misconceptions that have arisen about the meaning of this term. The dialectic logic that was championed by the group of scholars collectively known as the Frankfurt School is outlined and a number of implications for the field of organization and behaviour are discussed. INTRODUCTION Readers of this journal, and those who seek to inhabit the fields of organization theory and behavior, will be all too aware of the turbulence that has been created by postmodernist theorising and the revival of the debate over the incommensurability of paradigms. Some of the discourse seems to be nothing more than cacophony of discordant voices and, at times, the field seems more akin to a battleground. At other times it seems the refuge of incommensurability provides a safe haven for those who wish to talk past one another. Some within the fields are intent upon finding a path of rescue. For some that path of rescue is about trying to find a synthesis from some meta-theoretical Archimedean point that they believe is an indisputable “fact” or position to “ground” the field(s). Others have sought a path of rescue where what is championed seems to be a fairly infantile argument that “my paradigm is better (bigger) than yours”. Some others in the fields appear more relaxed, finding virtue in diversity and incommensurability as it seems to put a brake on those seeking a hegemonic takeover of the fields themselves. -------------------* Adrian N. Carr, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor and Principal Research Fellow in Organization Studies and Applied Social Sciences, School of Social Sciences, University of Western Sydney, Australia. His research interests are in the application of psychodynamic and critical theory to management and organization studies. Copyright © 2005 by PrAcademics Press CHALLENGE OF CRITICAL THEORY FOR THOSE IN ORGANIZATION THEORY AND BEHAVIOR 467 This paper in no way seeks to rescue the fields with some new form of synthesis or new Archimedean point from which we can move on from these current debates. Instead, this paper seeks to address the growing trend of people in the field to revisit, re-engage, or re-discover critical theory. There has been a revival in interest in critical theory in both the fields of organization theory and organization behavior (see Carr, 2000). Critical theory was seen as quite radical when it first appeared. Indeed, I am sure my reader would be familiar with Burrell and Morgan’s 1979 tome entitled Sociological paradigms and organizational analysis. This work stimulated the start of a significant discourse in organization studies, about paradigms, and it might be recalled that in this work they put forward the four narratives that they deemed were mutually exclusive, or incommensurate, views of the social world, namely: radical humanist; radical structuralist; interpretive; and functionalist. Critical theory was viewed as being “radical humanist”. Interestingly, Burrell has subsequently become one of the pioneers of postmodernism, in the field of organization studies, and in his volume Pandemonium: Towards a retro-organization theory declares that he wishes to leave the aforementioned four “equally sized rooms he has been stalking" (Burrell, 1997; see also Carr, 1997). He has forsaken that venture for a new journey, that of postmodernism. The mantle of “radical” now appears to have been taken by postmodernist theorising despite the fact that this theorising leads to a very conservative political agenda (Carr, 1996; Zanetti & Carr, 1999). The revival in interest in critical theory is one that certainly has benefited from postmodernists raising some of the very same issues raised by critical theorists, but the “solutions” are generally quite different for the two groups of theorists. Indeed, the confluence is such, we can note instances where even those who are revered as postmodernists have discovered critical theory as holding some reflexive significance that they subsequently “discover”. In this context, it is worthy of note that, for example, Foucault cites the work of the critical theorist Adorno (1973; 1984), such that one social commentator observes that: A decade and a half after Adorno’s death, Michel Foucault … said: ‘If I had known about the Frankfurt School in time, I would CARR have been saved a great deal of work. I would not have said a certain amount of nonsense and would not have taken so many 468 CARR false trails trying not to get lost, when the Frankfurt School had already cleared the way’. Foucault described his programme as a ‘rational critique of rationality’. Adorno had used almost exactly the same words in 1962 in a lecture on philosophical terminology. Philosophy, Adorno had said, should conduct ‘a sort of rational appeal hearing against rationality’ (Wiggershaus, 1994, p. 4) The revival of interest in critical theory has been such that a number of publishers have commissioned, or otherwise committed to, a series of volumes that represent very recent translations of correspondence and unpublished papers of the founders of critical theory.(1) In some of the recent “euphoria” of writing in the genre of critical theory we have, unfortunately, witnessed some interpretations and views about critical theory that demand correction. This paper seeks to outline what critical theory is and what it is not. The paper also endeavours to illustrate the implications for organization theory and behavior if critical theory is to be embraced. Our first task is to gain an appreciation of the fundamental arguments that are championed by critical theory. CRITICAL THEORY: WHAT IS IT?2 The term “critical theory” has a two-fold meaning. It is used to refer to a “school of thought”. At the same time it refers to a self-conscious critique that is aimed at emancipation through enlightenment and it is a form of critique that does not cling dogmatically to its own doctrinal assumptions (Giroux, 1983). Critical Theory as a School of Thought In regard to critical theory being associated with a “school of thought”, the body of work being referred is that of a group of scholars collectively known as “the Frankfurt School”. The Frankfurt School is so called because of the association of a social research group with its location, Frankfurt in Germany. This group of scholars worked at the Institut für Sozialforschung — the Institute for Social Research. This Institute was established in, but financially independent of, Frankfurt University in February 1923. The key figures that were associated with the Institute were Theodor Adorno (1903-1969), Erich Fromm (19001980), Max Horkheimer (1895-1973), Otto Kirchheimer (1905-1965), Leo Lowenthal (1900-1993), Herbert Marcuse (1898-1979), Franz Neumann (1900-1954), Friedrich Pollock (1894-1970), and somewhat CHALLENGE OF CRITICAL THEORY FOR THOSE IN ORGANIZATION THEORY AND BEHAVIOR 469 outside of inner group, Walter Benjamin (1892-1940). Collectively this group is often referred to as the “first generation” of the Frankfurt School the time period and the major themes they had as the focus of their work, somewhat, separating them from those that were also to be associated with the Frankfurt School such as Klaus Elder, Jürgen Habermas, Oskar Negt, Claus Offe, Alfred Schmidt and Albert Wellmer. The latter group are sometimes referred to as the “second generation”. In 1933, under the Nazi regime, the Institute was closed for what was described as “tendencies hostile to the state” (Jay, 1973/1996). Many members of the Institute were Jewish. Following a short time of incorporation in Geneva, the Institute relocated to New York City in 1934 and became affiliated with Columbia University. Given the neoMarxist orientation of this group it might seem a little strange that their “protective” haven was in the heartland of capitalism. Following the war some of the members of the Institute (Horkheimer, 1976; Adorno, 1973; 1984) returned to Frankfurt and re-established the Institute in 1949, while others (notably Marcuse and Fromm) remained in the States. Jürgen Habermas became a professor of philosophy at the Frankfurt University, before establishing his own research centre at the Max Planck Institute in Starnbeg, West Germany, in 1971. It is interesting to note that some theorists, at one level, no longer regard Habermas as a critical theorist for, while much of his work was initially undertaken at the Institute, his work has drawn its inspiration from pragmatism and systems theory rather than the fundamental dialectical orientation that is the infusion of critical theory (Zanetti & Carr, 1997). Indeed, a recently translated series of letters between Horkheimer (1976) and Adorno (1973; 1984) reveals that Horkheimer was of the view that Habermas’ work in the area of philosophy was “betraying philosophy and critical theory” and he would “bring shame to the Institute” (Kellner, 2001, p. 23). Thus, Habermas is a good example of where, even at this basic level of coming to terms with what is critical theory, we have a small “exceptions” to the general summary that is being argued in this section of paper. It is also the case that while the work of the group of critical theorists identified in the previous paragraphs displayed a very large degree of convergence, there were, nonetheless, significant disagreements some of which were extremely public. 470 CARR Critical Theory as a Process of Critique The second meaning of the terminology “critical theory” — which also simultaneously includes, as perhaps the major instance, the work of those associated with the Frankfurt School — resonates with a particular process of critique, the origins of which owe multiple allegiances. Critical theory aims to produce a particular form of knowledge that seeks to realize an emancipatory interest, specifically through a critique of consciousness and ideology. It separates itself from both functionalist/objective and interpretive/practical sciences through a critical epistemology that rejects the self-evident nature of reality and acknowledges the various ways in which reality is socially constructed and distorted. Although the theoretical orientation owes much to the work of Kant, Hegel and Marx, it was Horkheimer who first applied the phrase “critical theory” in a manner that was to become a shared meaning amongst the Frankfurt School scholars. In 1937, in a paper entitled Traditional and Critical Theory, Horkheimer (1976) attempted to distinguish between traditional theory and that which he called critical theory. Horkheimer viewed traditional theory as focused upon deriving generalisations about aspects of the world. This he saw as true, whether they were derived deductively (as with Cartesian theory), inductively (as with John Stuart Mill), or phenomenologically (as with Husserlian philosophy). Horkheimer argued the social sciences were different to the natural sciences, in as much, as generalisations could not be easily made from so-called experiences, because the understanding of experience itself was being fashioned from ideas that were in the researcher themselves. The researcher is both part of what they are researching, and caught in a historical context in which ideologies shape the thinking. Thus, theory would be conforming to the ideas in the mind of the researcher rather than the experience itself. The facts which our senses present to us are socially performed in two ways: through the historical character of the object perceived and through the historical character of the perceiving organ. Both are not simply natural; they are shaped by human activity, and yet the individual perceives himself (sic) as receptive and passive in the act of perception (Horkheimer, 1976, p. 213). CHALLENGE OF CRITICAL THEORY FOR THOSE IN ORGANIZATION THEORY AND BEHAVIOR 471 In the course of making this point, Horkheimer injected the Marxist, and most specifically, the Lukács notion of reification into his argument — specifically arguing that the development of theory “was absolutized, as though it were grounded in the inner nature of knowledge as such or justified in some other ahistorical way, and thus it became a reified, ideological category” (Horkheimer, 1976, p. 212). This was later to become the basis for another charge that traditional theory maintained a strict separation between thought and action. In contrast, critical theory was about insight leading to praxis and emancipation. Horkheimer insisted that approaches to understanding in the social sciences cannot simply imitate those in the natural sciences. Rasmussen (1996, p.18) frames Horkheimer’s resolution to the dilemma well, when he says: Although various theoretical approaches would come close to breaking out of the ideological constraints which restricted them, such as positivism, pragmatism, neo-Kantianism and phenomenology, Horkheimer would argue that they failed. Hence, all would be subject to the logico-mathematical prejudice which separates theoretical activity from actual life. The appropriate response to this dilemma is the development of a critical theory. What is required, Horkheimer (1976, p. 221) argues, is “a radical reconsideration not of the scientist alone, but of the knowing individual as such”. This solution to the problem through epistemology, is an approach of such significance it can not be overestimated. It signified how critical theory was not simply reflective of orthodox Marxism nor purely Hegelian — notwithstanding the fact that the Horkheimer paper can be seen as deeply influenced by the Hegelian-Marxist idea of the individual alienated from society. Indeed, it was Marx’s Capital: Critique of Political Economy (1906) that largely served as the touchstone paradigm from which resonance and departures were made by the Frankfurt School. However, the epistemological turn gave critical theory a “critique” of a different kind. Contra Marxism that sought to apply a specific template or straight-jacket to both critique and action, which itself was historically contingent, and contra-Hegelian thought that privileges consciousness, critical theory was about being self-critical and rejects any pretensions to absolute truth. Critical theory defends the primacy of neither matter (materialism) nor consciousness (idealism), 472 CARR arguing that both epistemologies distort reality to the benefit, eventually, of some group. In this approach, what critical theory attempts to do is to place itself outside of philosophical strictures and the confines of existing structures. As a way of thinking and “recovering” humanity’s self knowledge, critical theory often looks to Marxism for its methods and tools. Whilst critical theory must at all times be self-critical, Horkheimer insists a theory is only critical if it is explanatory, practical and normative all at the same time — or, as Bohman, in summarising Horkheimer’s criteria, states: “it must explain what is wrong with current social reality, identify actors to change it, and provide clear norms for criticism and practical goals for the future” (Bohman, 1996, p. 190) The focus of critical theory is simply not to mirror “reality” as it is, which is what traditional theory seeks to do, but to change it — in Horkheimer’s (1976, p. 219) words, the goal of critical theory is “the emancipation of human beings from the circumstances that enslave them”. This, of course, required the Frankfurt School scholars to address their attention to issues that arise in a variety of domains, such as cultural, political, economic, intellectual (including epistemological) and psychological. Raymond Guess (1981, pp. 1-2), in his book The Idea of Critical Theory, suggests the following fundamental theses underpinned the Frankfurt School notion of critical theory: - Critical theories have special standing as guides for human action in that: (a) They are aimed at producing enlightenment in the agents who hold them, i.e. at enabling those agents to determine what their true interests are; (b) They are inherently emancipatory; i.e., they free agents from a kind of coercion which is at least partly self-imposed, from self-frustration of conscious human action. - Critical theories have cognitive content; i.e., they are forms of knowledge. - Critical theories differ epistemologically in essential ways from theories in the natural sciences. Theories in natural science are “objectifying”; critical theories are “reflective”. The above ingredients were not only seen by the Frankfurt School scholars as an epistemic structure characterising their own work, but also CHALLENGE OF CRITICAL THEORY FOR THOSE IN ORGANIZATION THEORY AND BEHAVIOR 473 the work of Freud.(3) The appreciation of this similarity was to become important for particularly one of their number, namely Herbert Marcuse. He was to explore the manner in which psychodynamic processes could be manipulated to facilitate forms of self-repression and consent to systems of collective representation that are not in the individuals’ own best interests, but instead served to legitimate the interests of others. We will note this matter in some greater detail presently, but while we are endeavouring to understand the Frankfurt School scholars’ notion of critical theory we need to round out such a discussion with an appreciation of dialectics. The critique and action of critical theory presupposed, and was infused with, a dialectic vision (see Carr, 1989). DIALECTICS: A KEY INGREDIENT One of the standard references to the history of the Frankfurt School is Martin Jay’s book The Dialectical Imagination (1973/1996). This title captures a crucial feature of the Frankfurt School vision. Critical theory was theory that presupposed and was imbued with dialectics for it was the form of connection that relates consciousness about “truth”, “falsity” and domination with the issues of history, origin and purpose in society. One could say that the Frankfurt School scholars firmly shared Marx’s view that: “Dialectic is unquestionably the last word in philosophy” (Kellner, 2001, p. 6). The dialectic “logic” used by members of the Frankfurt School is evident throughout their work, perhaps no more so than in their critique of positivism and pragmatism. One of the major assumptions of positivism that critical theory challenged was that Nature, or an external reality, is the author of truth or “fact”. The concept of valid knowledge being detached (and therefore neutral) from particular knowing subjects is rejected. Instead, the Frankfurt School championed a dialectical logic. Marcuse (1993, p. 445) expressed this view succinctly when he argued: Dialectical thought invalidates the a priori opposition of value and fact by understanding all facts as stages of a single process — a process in which subject and object are so joined that truth can be determined only within the subject-object totality. All facts embody the knower as well as the doer; they continuously translate the past into the present. The objects thus “contain” subjectivity in their very structure. 474 CARR Thought itself is a product of discourses and social experiences in which we are an agent. Interestingly, both critical theory and postmodernist theorising emphasize the manner in which object and subject, thought and being are mediated by each other and “thus reject the principle reductive idealist or materialist thought” (Best & Kellner, 1991, p. 224). Adorno, similarly, argued that “facts are not in society ... the resting point on which knowledge is founded because they themselves are mediated through society” (cited in Spinner, 1975, p. 78, italics is added emphasis). Adorno is denying the finality on which all knowledge is presumed to rest. Instead, like others in the Frankfurt School, Adorno put the view that there was a constant interplay of particular and universal, of moment and totality. Thus, for critical theory, the relationship between totality and its moments are to be seen as reciprocal. All cultural phenomena are to be viewed as mediated through the social totality. This form of argumentation by Adorno, Horkheimer and Marcuse is one that comprehends events and engages in a form of reflection that is dialectic logic. This dialectical thinking owes much to the work of Hegel and Marx. Hegel’s notion of dialectics fundamentally involved recognition that the particular and the universal were interdependent. It might be recalled that Hegel developed three fundamental “laws” of dialectical thought. These were: - The law of the transformation of quantity into quality, and viceversa; - The law of the unity (interpenetration, identity) of opposites; - The law of the negation of negation (Guest, 1939, p. 45). It was the second of these laws that was viewed as the crucial idea in dialectics as a method. Indeed, Lenin in his Notes on Hegel’s Logic, wrote: “Dialectics may be briefly defined as the theory of the unity of opposites” (cited in Guest, 1939, p. 51). “Opposites” are viewed not as existing as being in stark contrast to each other, but existing in unity. Hegel (cited in Wallace, 1975, p. 222, italics is original emphasis) expresses this relationship, arguing: Positive and negative are supposed to express an absolute difference. The two however are at bottom the same; the name of either might be transformed to the other. … The North Pole of the magnet cannot CHALLENGE OF CRITICAL THEORY FOR THOSE IN ORGANIZATION THEORY AND BEHAVIOR 475 be without the South Pole and vice versa. … In opposition the difference is not confronted by any other, but by its other. The co-existence of opposites was viewed as the essential contradictory character of reality. It was this contradictory character that provided the evidence of the manner in which things developed. Lenin was to describe contradiction as “the salt of dialectics” and argued that “the division of the one and the cognition of its contradictory parts is the essence of dialectics” (cited in Guest, 1939, p. 48, italics is original emphasis). Hegel viewed dialectical thought as akin to “dialogue” in which the conflict of opinion results in the emergence of a “new” viewpoint. The dialectic, as such, was conceived as a “motion” involving three “moments”: thesis, antithesis and synthesis. McTaggart (1896, pp. 9-10) captures this dynamic when he notes: The relation of the thesis and the antithesis derives its whole meaning from the synthesis, which follows them, and in which the contradiction ceases to exist as such ... An unreconciled predication of two contrary categories, for instance Being and not-Being, of the same thing, would lead in the dialectic ... to scepticism if it was not for the reconciliation in Becoming ... [Thus] the really fundamental aspect of the dialectic is not the tendency of the finite category to negate itself but to complete itself. While the Frankfurt School scholars did not accept the notion of “dialectical laws of nature”, their concept of dialectic owes much to this Hegelian formulation. Most philosophers have supposed that a philosophical system must have some foundation, some starting point upon which knowledge is built. Descartes, for example, supposed that if the point of departure can be shown to be true, and if the reasoning away from this point is absolutely rigorous, then the result must also be true. If truth is present at the departure point, it is preserved and reappears at the end of the process. Hegel, however, rejected the validity of such a Cartesian foundation with its linear logic. The danger of establishing a foundation is that knowledge is completely derailed when the foundation crumbles or must be abandoned. Wishing to develop a logic that would capture the ebb and flow of life itself, Hegel reached back to the Platonic dialogues for inspiration. The dialectical process begins with a “thesis”, any definable reality that is the starting point from which all further development proceeds. As is 476 CARR noted above, reflection progresses and this thesis is seen to encompass its opposite, or “antithesis”, as part of its very definition. One “moment” of the dialectic process gives rise to its own negation. The process is comparable to tragedy in which the protagonist is brought down as a result of the dynamics inherent in his/her own character. What emerges from the dialectic of affirmation and negation is a transcendent moment that at once negates, affirms, and incorporates all the previous moments. Thus, the thesis should be understood to have possessed the seeds of its antithesis all along. If thought focuses appropriately on the reciprocal relationship between the thesis and antithesis, a synthesis emerges. The synthesis is the understanding of the unity that holds between the two apparent opposites, and which permits their simultaneous existence. The familiar triadic structure of Hegelian thought is, thus, not simply a series of building blocks. Each triad represents a process wherein the synthesis absorbs and completes the two prior terms, following which the entire triad is absorbed into the next higher process. Hegel himself preferred to refer to the dialectic as a system of negations, rather than triads. His purpose was to overcome the static nature of traditional philosophy and capture the dynamics of reflective thought. The essence of the dialectic is this ability to see wholes and the conflict of parts simultaneously. As Adorno (1984, p. 38) expressed it, “Dialectics is the quest to see the new in the old instead of just the old in the new. As it mediates the new, so it also preserves the old as the mediated”. Rather than viewing matters in linear cause-and-effect terms dialectical thinking calls attention to the ongoing reciprocal effects of our social world. Marx viewed the Hegelian dialectic as somewhat idealist and reworked the notion by turning it on its head, arguing the theoretical abstractions are formed from the lived experience of historically-based and evolved social relations — not in the reverse pattern as envisaged by Hegel. Marx’s “historical materialism” was a dialectic of the “real world”, as Marx (1906, p. 25) himself argues: My dialectic method is not only different from the Hegelian, but is its direct opposite. To Hegel ... the process of thinking, which, under the name of ‘the Idea’, he transforms into an independent subject, is the demiurgos of the real world, and the real world is only the external phenomenal form of the ‘Idea’. With me, on the contrary, the idea is nothing else than the material world reflected by the human mind, and translated into forms of thought. CHALLENGE OF CRITICAL THEORY FOR THOSE IN ORGANIZATION THEORY AND BEHAVIOR 477 Marx retained the concept of contradiction being at the root of transformative processes and saw contradiction was an effect that is implicit in the social structure, or institutional form, itself — the opposition is inherent in the totality, in the same way death is implicit in birth. For Marx, structure did not arise from or act independently of the thoughts, desires and actions of human agents but from the critical and transformational aspects of dialectics. Watkins (1985, p. 7) notes that the implications of this when he says “it is from this view, with human agents as active and praxis-inclined, that the transformation of institutions through the transcendence of the existing contradictions occurs”. The Frankfurt School rejected the class interest analysis that came with a Marxist orientation and placed its emphasis in understanding cultural phenomenon as mediated through the social totality. Contra the orthodox Marxist view, the economic system could not be extracted and analysed other than in its broader context. While the founding members of the Frankfurt School embraced the Hegelian foundation of dialectics, they did, however, rejected his claims to absolute truth, preferring a historical contextual interpretation. For the Frankfurt School scholars, truth was a mediated truth, and part of that mediation was the historical period. Part of that “truth” also came from the ideologies that were distributed through a “culture industry” and yet another part was to be “found in the material reality of those needs, desires and wants that bear the inscription of history. That is, history is to be found as “second nature” in those concepts and views of the world that make the most dominating aspects of the social order appear to be immune from historical socio-political development” (Giroux, 1983, p. 32). This “second nature”, Jacoby (1975) was to remark, is history hardened into a form of “social amnesia”, that is a mode of consciousness that forgets its own ontology. This suppression of history “is not an academic but a political affair” (Marcuse, 1964, p. 97). This became a crucial issue for the Frankfurt School, particularly Marcuse in his critique of psychology as being too cognitive and ahistorical in its recognition of where needs, want and desires become fashioned. For the Frankfurt School, critical theory and a dialectic optic was needed to unmask these forms of psychological and social domination and simultaneously engender liberation. Thus, for the Frankfurt School, to embrace the critical theory’s attention to the issue of dialectics is to embrace a perspective that draws 478 CARR attention to the social totality and our mediated existence. No aspect of our life world can be understood in isolation. For the “philosophically supple” (Carr, 1997) this tenet for enquiry, as Bauman (1976) and Ritzer (1996) point out, has both a synchronic and diachronic aspect. The synchronic aspect is that we are drawn to consider the interrelationship of “components” of a society within a totality. The diachronic aspect is that we are drawn to consider a historical dimension of society. Geuss (1981, p. 22) in similar vein, notes that “one of the senses in which the Critical Theory is said by its proponents to be ‘dialectical’ (and hence superior to its rivals) is just in that it explicitly connects questions about the ‘inherent’ truth or falsity of a form of consciousness with questions about history, origin and function in society”. Detecting “truth” and “falsity”, the suppression of history and the issue of “social amnesia” were matters that led Adorno and Marcuse, in particular, to further refinements of “dialectics”. The awareness of the dynamics of the current social order, and the manner in which that social order institutionalised forms of social repression, was very dependent upon the extent to which the “negative” and contradictions could be brought to a conscious awareness. Our sobriety in this regard is not easily achieved, both in the sense of having the “tools” to assist awareness of contradiction and thus penetrate false images and “false consciousness;” as well as, dealing with the emotional turmoil and discomfort that such an awareness may bring. Marcuse, in a slightly different context (see Carr & Zanetti, 2000) referred to the estrangement-effect in relation to the clash of the conflicting “realities” and he likened it to the way in which the surrealists elicited such feelings and discomfort when they, for example, juxtaposed objects in unfamiliar association and elicited unforeseen affinities between objects and, perhaps, unexpected emotion and sensations in the observer. It was in this discomfort that the conditions for seeing the world anew arose. In the tradition of Hegel, Fredric Jameson (1971, p. 308, italics is added emphasis) points out, correctly in my view, that: But precisely because dialectical thinking depends so closely on the habitual everyday mode of thought which it is called on to transcend, it can take a number of different and apparently contradictory forms. So it is that when common sense predominates and characterizes our normal everyday mental atmosphere, dialectical thinking presents itself as the perversely hairsplitting, as the overelaborate and the oversubtle, reminding CHALLENGE OF CRITICAL THEORY FOR THOSE IN ORGANIZATION THEORY AND BEHAVIOR 479 us that the simple is in reality only a simplification, and that the self-evident draws its force from hosts of buried presuppositions. Marcuse was all to acutely aware that these moments of revelation were all too easily muted or disarmed by assimilating mechanisms of the prevailing order. The estrangement-effect can only be maintained to the extent that it continues to reveal the prevailing order in its opposition and (simultaneously) the opposition in the prevailing order — that is, to the extent that it maintains a dialectical tension. The opposition between antagonistic spheres is a dynamic conceived as the mediation of one through the other (see Marcuse, circa unknown/1993). This concern was also shared by Adorno who went in a different direction to posit a postHegelian dialectic approach that postponed indefinitely the “closure” represented in “synthesis” and also freed dialectics from the affirmative qualities in Hegel’s three laws of dialectic thought, particularly that related to negation of the negation. In his work Negative Dialectics (1966/1973), Adorno championed a modification of dialectical thinking in which, as its most basic example, he suggests that freedom can only be defined in negative terms for it corresponds only to specific forms of un-freedom — again, social and historical contexts were crucial in understanding. Adorno (1973, p. 299) expressed his formulation as follows: The subjects are free, after the Kantian model, in so far as they are aware of and identical with themselves; and then again, they are unfree in such identity in so far as they are subjected to, and will perpetuate, its compulsion. They are unfree as diffuse, nonidentical nature; and yet, as that nature they are free because their overpowering impulse — the subject’s non-identity with itself is nothing else — will also rid them of identity’s coercive character. The form of reflective openness, contained in Adorno’s Negative Dialectics, does not affirm any specific “synthesis” and acts against what he saw as the predilection of humans to seek closure as an act of mastery and control. We will gain a firmer understanding of this in the next section of this paper in which this author seeks to round out the discussion of critical theory and dialectics by identifying some common misconceptions carried in social science discourses. CRITICAL THEORY: WHAT IT IS NOT 480 CARR The revival in interest in critical theory has also been witness to a revival in a number of misconceptions that have appeared in numerous discourses, not least of which being organization theory discourse. The original understanding has, to some extent, been contaminated and these misconceptions need addressing not only to correct the “record” for those who wish to adopt critical theory in their own work, but also in the interests of further clarifying what critical theory is. The first, and perhaps most common, misconception is that every framework presenting two sides of a question or situation is dialectical. This is not the case. Adorno notes: “Dialectical thought is the attempt to break through the coercive character of logic with the means of logic itself” (Adorno, cited in Arato and Gebhardt, 1982/1993, p. 396). In other words, dialectical thought steps within the framework of an argument to offer its critique. Juxtaposition, static opposition, and simple divisions certainly exist, but these are, by definition, undialectical and simple dualisms, since dialectic thinking requires that the conditions and circumstances of the whole be taken into consideration as well. As we will elaborate presently, dialectic incorporates a "substantive" contradiction, rather than simply a formal-quantitative one. A second misconception relates to a simplistic reduction of the familiar thesis-antithesis-synthesis relationship. A perception seems to have arisen that the synthesis is analogous to compromise, a kind of middle ground halfway between the two original starting points. This misinterpretation quite possibly stems from the words Hegel used to describe this new thought process — Vermittlung (mediation) and Versöhnung (reconciliation) — as well as, one suspects, from the insistence of textbook editors on offering two-dimensional graphic representations of such a holistic process. Horkheimer speaks contemptuously of the tendency to represent dialectic as a "lifeless diagram” (1935/1993, p. 414). What is often overlooked in these simplistic formulations is that mediation takes place in and through the extremes (the thesis and antithesis); it is not a simple give-and-take along a continuum. Dialectic is a more supple form of thought than mathematical inference. It always makes higher-order comments on the relationship under scrutiny, stating connections that carry beyond the obvious content. The synthesis becomes a new “working reality”— a “new working constellation of the thesis and antithesis” (Arato & Gebhardt, 1982/1993, p. 398) — and may, in turn, become a thesis (which then engenders its own antithesis). The contradiction is not “resolved”, but instead absorbed: the frame of reference which made the CHALLENGE OF CRITICAL THEORY FOR THOSE IN ORGANIZATION THEORY AND BEHAVIOR 481 poles opposites in the first case is transcended. Thus, what might appear to be opposites in one context (force and consent, for example) might no longer be opposites in a different context. A third common misconception, very much intertwined with the misconception just outlined, refers to the nature of contradiction represented by the dialectic and the binary oppositional thinking that appears in much Western thought. We talk about right or wrong; rational or emotional; nature or nurture; public or private; heart or head; quality or quantity, etc. These are very familiar oppositions. Embedded in this fundamental style of traditional thinking (or formal logic), however, are not only oppositions but also hierarchy, in that the existence of such binaries suggests a struggle for predominance. If one position is right, then the other must be wrong. Hélène Cixous (1986, p. 2) observes that the oppositional terms are locked into a relationship of conflict and, moreover, this relationship is one in which one term must be repressed at the expense of the other. Nature without nurture seems meaningless, for example, but often nurture struggles to negate the influence of nature. Irigaray (see Whitford, 1991) has similarly observed that one of the principles of Western rationality is that of non-contradiction, where we strive to reduce ambivalence and ambiguity to an absolute minimum. In such a logical system, two propositions cannot be true simultaneously (Popper, 1963). This is so because traditional logic focuses on empirical (mostly quantitative) representations of reality, necessarily builds on arbitrarily constructed foundations. At some point, the logic is abstracted from reality (formalized). Thus, in this “system” of logic one proposition must prevail, and the other must accordingly be vanquished. In critical theory, however, form cannot be separated from content. It must continually reflect the whole of reality, not just a simplification of it. But because of the pervasiveness of binary oppositional thinking, the term dialectic sometimes gets mistakenly used to denote a simple binary of opposites where the dialectical contradiction (the thesis-antithesis) is in some fashion conceived as an absolute. Dialectical relationships do not express simply existence and nonexistence; they also recognize the other possibilities available in the whole. For example, “the dialectical contradiction of ‘a’ is not simply ‘non-a’ but ‘b’, ‘c’, ‘d’, and so on — which, in their attempt at selfassertion and self-realization, are all fighting for the same historical space” (Arato & Gebhardt, 1982/1993, p. 398). Horkheimer gives other examples of such dialectic logic and suggests we need to think in terms 482 CARR of substantive opposites rather than formal/logical positivist/logical empiricist ones to help in understanding our assumptions. He gives an example of the contradiction to “straight” which formal logic might seem to suggest is “non-straight”, but Horkheimer (1935/1993) offers other negations: “curved”, “interrupted”, and “zigzag”. Another example might be to recognize that there are multiple negations to power: resistance, powerlessness, and quiescence, all of which have different relationships to power and consequently different dialectical resolutions. Thus, “true logic, as well as true rationalism, must go beyond form to include substantive elements as well” (Jay, 1996, p. 55). A fourth misconception arises from a misunderstanding that critical theory is merely critique and therefore only capable of being a negative discourse. Marcuse (1993) succinctly puts the counter-argument when he says: The liberating function of negation in philosophical thought depends upon the recognition that the negation is a positive act; that-which-is repels that-which is-not and, in doing so, repels its own real possibilities. Consequently, to express and define thatwhich-is on its own terms is to distort and falsify reality. Reality is other and more than that codified in the logic and language of facts (p. 447). … Dialectical logic is critical logic: it reveals modes and contents of thought which transcend the codified pattern of use and validation. Dialectical thought does not invent these contents; they have accrued to the notions in the long tradition of thought and action. Dialectical analysis merely assembles and reactivates them; it recovers tabooed meaning and thus appears almost as a return, or rather a conscious liberation, of the repressed! Since the established universe of discourse is that of an unfree world, dialectical thought is necessarily destructive, and whatever liberation it may bring is s liberation in thought, in theory. However, the divorce of thought from action, of theory from practice, is itself part of the unfree world. No thought and no theory can undo it; but theory may help to prepare the ground for their possible reunion, and the ability of thought to develop a logic and language of contradiction is a prerequisite for this task (p. 449). Marcuse uses a different view of “negative” and negation to that used by Adorno in his negative dialectics. The life-world for Marcuse is CHALLENGE OF CRITICAL THEORY FOR THOSE IN ORGANIZATION THEORY AND BEHAVIOR 483 one grounded in social change. The “negativity” in dialectics is in its non-affirmation and in this critical trajectory the destruction of what passes as common sense is a disrobing act to reveal buried presuppositions. Thus, as Marcuse argues, negation provides an important reflective function through the modality of estrangement — it is destructive, but the destruction re-emerges in a positive act. CRITICAL THEORY: SOME IMPLICATIONS FOR ORGANIZATION THEORY AND BEHAVIOUR The embrace of critical theory with its dialectic optic of the world has a number of implications for those who toil in the field for organization theory and behaviour. Gathered under three minor headings, this author wishes to briefly highlight inter-related issues that demonstrate the contemporary relevance of critical theory. In Relation to Researcher-Subject Connection and Theory Development The Frankfurt School scholars were concerned with the fetish with facts and the belief in value neutrality. This, in their view, was more than an epistemological error: it was a form of ideological hegemony infused with positivism and political conservatism. Researchers in the field of organization theory and behaviour need to be reflective about the “tools” that they seek to use, as well as become more sceptical as to empiricist claims. Much of the field has embraced a natural science paradigm and, in large measure, held structural functionalist and behaviourist visions of the world (see Carr, 1989). Critical theory rejects such a paradigm and optic of the world and the absolutizing of facts. Our world is a mediated world and, as we noted earlier in a citation to Horkheimer’s work, the researcher is part of that mediated world. The researcher is both part of what he/she is researching and caught up in the pervading ideologies that shape our thinking. The logic of his argument is to view organisations (and organisation theory), as with all “social facts”, as taking their specific form from the interpretive framework of the viewer. In the social sciences, facts cannot be separated from values as the two are intertwined. As one critical theorist argues: "If our theories create the facts that are relevant to them, we can only explore truth within a framework that defines what it is” (Greenfield, 1993, p. 94). 484 CARR If knowledge is mediated by cultural, social and linguistic “structures” and practices, then, as such, its “truth” claims (facts) would seem to be inevitably relational — an orientation that postmodernists share with critical theorists. Thus it is worth reminding ourselves that, at best, the natural sciences can only ever observe and infer, yet the social sciences can actually ask its “subjects” and thus “discover” meaning and intentionality. As if to underline the point being made here, one writer recently in chastising the field of psychology for adopting a natural science paradigm, argues: But the adoption of a ‘paradigm’ that calls for pooled data and statistical manipulations more or less forecloses any realistic chance of explaining the understanding the individual case. Billy cuts a worm in half because Billy has a sadistic streak. Jimmy cuts a worm in half so that, with two, the worm will no longer be lonely. A ‘paradigm’ that features the outcome and ignores the rationale must miss everything that is of real importance, even as it painstakingly strives for accuracy in measurement and merely statistical significance (Robinson, 2000, p. 42). Knowledge would seem to be grounded in the subjective experiences of the individual. In this context, the issue for our organization theory discourse is not one of objective truth, but one of some transparency over how we come to hold the conclusions that we do. What logic, reason and other mediated pathways did we use (unconsciously guided), in coming to “believe” this was the truth. The challenge for the field is to make transparent such logic. In an effort to try to distance ourselves as researchers and theorists, from the mediated situation in which we find ourselves, critical theory would suggest we need to be aware of the dialectic tension in our theorising and be sensitive to the contradictions in our “texts”. Critical theorists would insist upon acknowledging that the field in which we toil, organizations are full of paradox, contradictions and irony. Detecting contradictions, and other such ruptures, is not an easy task when we ourselves are part of what we are researching. In short we need to be able to see ourselves in spite of ourselves. To do this requires we develop “tools” that help to create the estrangement that we discussed earlier. Certainly, critical theorists have a processual perspective that recognises the on-going dialectic tension of various theories, which in itself affords an opportunity to see afresh aspects of the lifeworld in organisations. Unlike those who view facts and treat them in their CHALLENGE OF CRITICAL THEORY FOR THOSE IN ORGANIZATION THEORY AND BEHAVIOR 485 immediate form as truth (and exclude knowledge of everything that is not yet fact), these theorists take the view that the form in which something immediate appears is not yet its true form. Dialectics requires that we take a given term, situation, etc and examine its negation. In analysing both the original term and its negation, we may become aware of new possibilities. Postmodernism with its “techniques” of deconstruction, playfulness, the clash-of-opposites, intertwining of form and content, metaphoricality and the like, unsettle us from our “conventional wisdom” and afford us an opportunity to penetrate and reflect, perhaps anew, on what we have taken for granted. Some in critical theory, while rejecting the so called “truth claims” made by postmodernists, have employed such techniques,(4) but always with a mind-set of gaining a clearer picture of the value-laden interests and the dialectic tensions at play. The optic of critical theory has led some to formulate research questions in a quite different manner to those of non-critically orientated approaches. For example, Colleen Capper (1998, p. 356) in her examination of administrative leadership in organizations suggests the following research questions are pertinent to a critical perspective: - Are the experiences, attitudes, values, and behaviours of persons from different social groups considered? How is what is happening in the situation perpetuating unequal relations among people? - How is the situation encouraging conformity and the abandonment of critical consciousness? - Who is benefiting from the situation? Whose interests are (and are not) being served by the situation? Whose knowledge/point of view is privileged? - To what extent is the situation a dodge or crisis point that serves to distract the people in the setting from working on issues of equity and justice? - How would people with social perspectives different from your own view the situation (in terms of gender/race, etc.)? Clearly the optics of critical theory put the research and the researcher in a very different place to that traditionally evident in mainstream discourse of organization theory and behaviour.(5) In Relation to Public Interest and the Body Politic 486 CARR It was noted earlier in this paper that critical theory must at all times be self-critical. Horkheimer also, however in the tradition of critical theory, insists a theory is only critical if it is explanatory, practical and normative all at the same time — or, as Bohman (1996) states in summarizing Horkheimer’s criteria: “it must explain what is wrong with current social reality, identify actors to change it, and provide clear norms for criticism and practical goals for the future” (p. 190, italics is added emphasis). The focus of critical theory is not to describe “reality”, but to change it. In Horkheimer’s (1976, p. 219) words, cited earlier in this paper, the goal of critical theory is “the emancipation of human beings from the circumstances that enslave them”. Clearly the embrace of a critical theory optic will require us to reflect upon the social totality and our mediated existence. No aspect of our lifeworld can be understood in isolation. Thus our theorising must recognise its own political import as well as be self-conscious as to the political context in which it relates to practice. As Ben Agger (1991) suggests: “There is something profoundly unreflexive about a theory that forgets its own connection to the body politic” (p. 187). It is the connection of theory to the “body politic” where critical theory poses a challenge to that of the field of organization theory and behaviour. Academics and other social researchers cannot embrace critical theory and at the same time act as though they do their work from a disinterested position. Such work is itself a political action. The positivist pretensions that facts and values can be kept separate, in research and analysis, is firmly rejected by critical theorists. To reflexively consider values and the context of the body politic, is part of analysis; it is not, in itself, to be confused with advocacy — an intellectual glide so often employed as a form of defence where any discussion of values is seen as undermining the “science” in research. To reflexively consider values is not to abandon “objectivity” or to compromise “distance”. Critical theory is all about making the distinction between subjectivity and objectivity, and what is and what should be. In its broader context that Agger (1998, p. 179) rightfully notes: Critical social theorists understand that objectivity in the social sciences is molten, not frozen, thus precluding lawful representations of society. They further see that objective analysis of society’s crises and contradictions is a form of political action designed to raise consciousness and produce radical change. As a narrative representing change or stasis, CHALLENGE OF CRITICAL THEORY FOR THOSE IN ORGANIZATION THEORY AND BEHAVIOR 487 social science either contributes to the change or stasis that it discloses. For example, when positivists suggest there are certain ‘laws’ governing gender relations, they contribute to that representation of gender by depressing people’s attempts to do gender differently. The manner in which we develop a critical distance from what we study and analyse and at the same time reflexively make the connections to values and a body politic, represents a challenge for the field. In Relation to the Notion of Administration/Management and Assumptions about Employment Relations The assumptions that we make about the relationship of structures, organization processes and the “nature” of actors in organizations can frame the way in which we not only conceive what are appropriate research questions for the field, but also cumulatively help frame what we are to regard as the proper tasks of administrators and managers in organizations. Much of our discourse carries a positivism that embraces behavourist assumptions about human beings and structural-functionalist assumptions about agency. Critical theory with its dialectic optic on the world has a very different view — a view well captured some years ago by Kenneth Benson (1977) in the journal Administrative Science Quarterly. Benson’s work was an early call to view organizations through an optic of dialectics. For Benson (1997, p. 3), dialectics “because it is essentially a processual perspective, focuses on the dimension currently missing in much organizational thought”. It was seen as a way to open up analysis to the processes through which people in organizations “carve out and stabilize a sphere of rationality and those through which such rationalized spheres dissolve” (p. 3). Benson suggested that such dialectical analysis proceeds on the basis of four fundamental premises, or principles. These are that: (1) people are continually in a process of constructing and reconstructing the social context; (2) social phenomenon need to be studied rationally as part of a totality or larger whole that has multiple connections; (3) social arrangements are exactly that, social constructions with latent possibilities of transformation that become conscious through inherent contradictions in those social orders; and, (4) there is a commitment to praxis, while recognizing the limits and potentials of present social arrangements (see Benson, 1977). 488 CARR This call to view organizations through the optic of dialectics requires managers and administrators to adopt a different orientation to their work. No longer focussed upon control, and rejecting the idea of the organization as a “thing”, managers/administrators needed to perceive their role (as with others in the organisation) as being an active one in a broader process of transformation in which they act and are acted upon. This transformation is such, that the manager/administrator should not simply become aware of dialectical relationships between structures and actors, but become more critical in the appraisal of the options in carrying through their tasks. Part of the role is to de-reify established social patterns and to expect contradiction to arise that will require a working through of the strains and tensions that arise. Wilson (1985, p. 139) argues: “Management … is a dialectical interplay of persons whose roles change from one part of the system to another, and who remain open to dialogue and discussion in their continuing concern for the care of public things”. The dimensions of how this dialectic optic effects the orientation of a manager and administrator, this author has detailed elsewhere (see Carr, 1989) but also in an Appendix to this paper he summarises and contrasts this dialectic orientation to that of what might be termed a technical orientation or notion of administration and management. The author makes the contrast, again, to highlight the connection of theory with practice. In the growing cult of MBAism that views management and administration as simply series of technical problems that have straightforward technical answers that can be summarised in handbooks and decision trees, dialectic approaches to our field have a very different set of implications and challenges. NOTES 1. See, for example, the Routledge series on the Collected papers of Herbert Marcuse a six volume publication edited by Douglas Kellner of which only three have, thus far, been published. See also the series published by Belknap of Harvard University Press of the Selected writings of Walter Benjamin edited by Marcus Bullock and Michael Jennings, a series that commenced in 1997 and Lonitz, H. Theodor W. Adorno and Walter Benjamin: The complete correspondence 1928-1940 (N. Walker, Trans). Cambridge, MA: Polity. CHALLENGE OF CRITICAL THEORY FOR THOSE IN ORGANIZATION THEORY AND BEHAVIOR 489 2. Some material contained in this and the following section of the paper represents an elaboration and refinement from some earlier work that the reader may also wish to consult (see Carr, 1989, Carr, 2000; Zanetti & Carr, 1997) 3. Interestingly in this context, the Frankfurt Psychoanalytic Institute was originally established in 1929 as a “guest Institute” within the Institute for Social Research and housed in the same building. This occurred at a time when psychoanalysis was not well regarded. The Frankfurt Psychoanalytic Institute was headed by Karl Landauer and Heinrich Meng until closed by the Nazis in 1933. 4. The issue of using postmodern techniques as tools within a critical theory framework has led to the founding of new journal in 2001 that is entitled: TAMARA: Journal of Critical Postmodern Organization Science. David Boje is the founding editor. 5. In what some might see as an extreme view, there are those within critical theory, who are organization theorists, who have wondered aloud that the field is not simply about researching and assembling “facts”, but more appropriately should be considered from the perspective of presenting a “moral vision of the world”. This view stems from the argument that as conventional epistemology cannot be appealed to as an adequate source of judgement for managers and administrators, we need a discourse not anchored in rationality, as it has been in the past, but anchored in values and a morally concerned scepticism. This would take the field and the focus of research in a different direction. Those wishing to know more about such a viewpoint, should read Greenfield & Ribbins (1993) and Carr (1997). REFERENCES Adorno, T. (1973). Negative Dialectics. New York: Seabury. (Original work published 1966) Adorno, T. (1984). Against Epistemology: A Metacritique (W. Domingo Trans.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. (Original work published 1956) Agger, B. (1991). A Critical Theory of Public Life: Knowledge, Discourse, and Politics in an Age of Decline. London, England: The Falmer Press. 490 CARR Agger, B. (1998). Critical Social Theories. Boulder, CO: Westview. Arato, A., & Gebhardt, E. (1993). “A Critique of Methodology: Introduction”. In A. Arato & E. Gebhardt (Eds.), The Essential Frankfurt School Reader (pp. 371-406). New York: Continuum. (Original work published 1982) Bauman, Z. (1976). Towards a Critical Sociology: An Essay on Commonsense and Emancipation. London, England: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Benson, J. (1977). “Organizations: A Dialectic View”. Administrative Science Quarterly, 22 (1): 3-21. Best, S., & Kellner, D. (1991). Postmodern Theory: Critical Interrogations. London, England: Macmillan. Bohman, J. (1996). “Critical Theory and Democracy”. In D. Rasmussen (Ed.), The Handbook of Critical Theory (pp. 190-215). Oxford, England: Blackwell. Burrell, G. (1997). Pandemonium: Towards a Retro-Organization Theory. London, England: Sage. Burrell, G., & Morgan, G. (1979). Sociological Paradigms and Organizational Analysis. London: Heinemann. Capper, C. (1998). “Critically Oriented and Postmodern Perspectives: Sorting out the Differences and Applications for Practice.” Educational Administration Quarterly, 34 (3): 354-379. Carr, A. (1989). Organisational Psychology: Its Origins, Assumptions and Implications for Educational Administration. Geelong, Victoria, Australia: Deakin University. Carr, A. (1996). “Putative Problematic Agency in a Postmodern World: Is It Implicit in the Text - Can It Be Explicit in Organisation Analysis?” Administrative Theory & Praxis, 18 (1): 79-86. Carr, A. (1997). “Responding to Paradigm Proliferation: Public Administration as a Moral Art?” Leading & Managing, 3 (1): 9-25. Carr, A. (2000). “Critical Theory and the Management of Change in Organizations.” Journal of Organizational Change Management , 13 (3): 208-220. CHALLENGE OF CRITICAL THEORY FOR THOSE IN ORGANIZATION THEORY AND BEHAVIOR 491 Carr, A., & Zanetti, L. (2000). “The Emergence of a Surrealist Movement and Its Vital ‘Estrangement-Effect’ in Organisation Studies”. Human Relations, 53 (7): 891-921. Cixous, H. (1986). “Sorties”. In H. Cixous & C. Clément (Eds.), The Newly Born Woman. Manchester, England: Manchester University. Geuss, R. (1981). The Idea of Critical Theory: Habermas and the Frankfurt School. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cambridge University. Giroux, H. (1983). Critical Theory and Educational Practice. Geelong, Australia: Deakin University. Greenfield, T., & Ribbins, P. (Eds.) (1993). Greenfield on Educational Administration. London, England: Routledge. Greenfield, T. (1993). “The Man Who Comes Back Through the Door in The Wall: Discovering Truth, Discovering Self, Discovering Organizations”. In T. Greenfield & P. Ribbins (Eds.), Greenfield on educational administration (pp. 92-121). London, England: Routledge. (Original work published 1980) Guest, D. (1939). Dialectical Materialism. New York: International Publishers. Horkheimer, M. (1976). “Traditional and Critical Theory”. In P. Connerton (Ed.), Critical sociology: Selected readings (pp. 206224). Harmondsworth, England: Penguin. (Original work published in German 1937) Horkheimer, M. (1993). “On the Problem of Truth”. In A. Arato & E. Gebhardt (Eds.), The Essential Frankfurt School Reader (pp. 407443). New York: Continuum (Original work published in 1935). Jacoby, R. (1975). Social Amnesia: A Critique of Conformist Psychology from Adler to Laing. Boston, MA: Beacon. Jameson, F. (1971). Marxism and Form. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University. Jay, M. (1996). The Dialectical Imagination: A History of the Frankfurt School and the Institute of Social Research 1923-1950. Berkeley, CA: University of California. (Original work published in 1973) 492 CARR Kellner, D. (2001). “Introduction”. In D. Kellner (Ed.), Towards a Critical Theory of Society: Collected Papers of Herbert Marcuse (pp. 1-33). London, England: Routledge. McTaggart, J. (1896). Studies in the Hegelian Dialectic. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University. Marcuse, H. (1964). One Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society. London, England: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Marcuse, H. (1993). “A Note on Dialectic”. In A. Arato & E. Gebhardt (Eds.), The Essential Frankfurt School Reader (pp. 444-451). New York: Continuum. (Original work published 1960) Marcuse, H. (1993). “Some Remarks on Aragon: Art and Politics in the Totalitarian Era”. Theory, Culture & Society, 10 (2): 181-195 (Circa of original work is unknown). Marx, K. (1906). Capital: Critique of Political Economy. Chicago, IL: Kerr and Co. Popper, K. (1963). Conjectures and Refutations. New York: Harper Torchbooks. Rasmussen, D. (1996). “Critical Theory and Philosophy”. In D. Rasmussen (Ed.), The Handbook of Critical Theory (pp. 11-38). Oxford, England: Blackwell. Ritzer, G. (1996). Sociological Theory (4th ed.). New York: McGrawHill. Robinson, D. (2000). “Paradigms and ‘The Myth of Framework’: How Science Progresses”. Theory & Psychology, 10 (1): 39-47. Spinner, J. (1975). “The Development of West German Sociology since 1945”. In R. Mohan & D. Martindale (Eds.), Handbook of Contemporary Developments in World Sociology (pp. 71-97). London, England: Greenwood. Wallace, W. (1975). The Logic of Hegel. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press. Watkins, P. (1985). Agency and structure: Dialectics in the administration of education. Geelong, Australia: Deakin University. CHALLENGE OF CRITICAL THEORY FOR THOSE IN ORGANIZATION THEORY AND BEHAVIOR 493 Whitford, M. (1991). Luce Irigaray: Philosophy in the Feminine. London, England: Routledge. Wiggershaus, R. (1994). The Frankfurt School (M. Robertson, Trans.), Cambridge, Massachusetts: Polity. Wilson, H. (1985). Political Management: Redefining the Public Sphere. New York: Walter de Gruyter. Zanetti, L., & Carr, A. (1997). “Putting Critical Theory to Work: Giving the Public Administrator the Critical Edge”. Administrative Theory and Praxis, 19 (2): 208-224. Zanetti, L., & Carr, A. (1999). “Exaggerating the Dialectic: Postmodernism's ‘New individualism’ and the Detrimental Effects on Citizenship.” Administrative Theory & Praxis, 21 (2): 205-217. APPENDIX 1 494 CARR A Technical and Dialectic Notion of Administration and Management Technical notion Dialectic notion 1. People are passive, optimistic 1. People are active and social, and can have and cipher-like, with little autonomy in determining their actions. The autonomy. The organisation degree of autonomy is inversely structure is a predetermined proportional to the extent of surplus “thing”, acting independently repression. The organisational structure is of the thoughts, desires and conceived as being in a process of actions of human agents. transformation - a process involving a dialectical relationship with human agency. 2. Organisations are abstractions 2. Organisations are not abstractions but are from their general environment representations of rationality (they may with the administrator contain the specific reality principle) and primarily responsible for the results of previous dialectic processes. control, fine tuning and acting The generative force of change is on personnel to achieve contradictions - contradictions that emerge equilibrium. Changes that take from the totality of the social world. place occur as a result of the Stability is not the norm but transient and demands placed on the represents a state of obstructed change. organisation by factors external Administrators should not be preoccupied to it. with control but with working out tensions and strains arising from contradictions. 3. Social relations are conceived 3. Social relations have a time and place of in a positivistic manner as dimension which recognises that human being “technical problems”, agents shape organisational structures while thus removing areas of social being themselves subject to their own relations from political debate. historical chain of experiences. Part of the tool kit for “fixing” Administrators should therefore not only be the technical problems is aware of the dialectic between structure and conventional organisational human agency but, as part of working out theory which itself is the tensions and strains arising from embedded in a structural- contradictions, should open up analysis of functionalist perspective of the the processes through which the current social world. structures, powers, etc. came into being and how they might transform existing negations. APPENDIX 1 (Continued) 4. The end results of adminis- 4. Administrative action is part of an trative action are assessed in ongoing process to detect contradictions terms of technical efficiency. and work through existing and/or potential The tenets of scientific mana- tensions and strains without a fundamental gement provide an appropriate desire to preserve a status quo. CHALLENGE OF CRITICAL THEORY FOR THOSE IN ORGANIZATION THEORY AND BEHAVIOR 495 context in which to conceive administrative action. 5. Facts are treated in their 5. The form in which something immeimmediate form as truth and diately appears is not yet its true form and exclude knowledge of every- what one sees is a negative condition and thing that is not yet fact. not the real potential. 6. The technical notion draws 6. The conflict perspective of society is from the structural functionalist drawn upon as the conceptual prism. perspective of society as its conceptual prism, embracing positivism, scientific management, classical organisation theory and behaviourism.