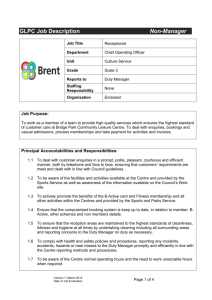

Authority and Reason

advertisement