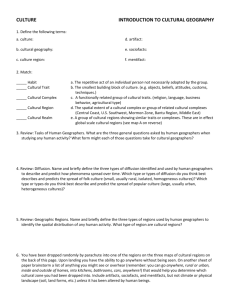

THE CULTURAL APPROACH IN GEOGRAPHY

advertisement