Toxic Environment Paper - University of British Columbia

advertisement

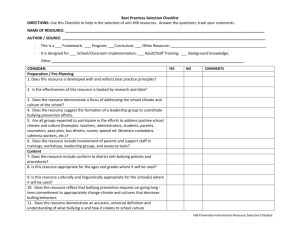

1 Escaping Bullying: The Simultaneous Impact of Individual and Unit-Level Bullying on Turnover Intentions Sandra L. Robinson Marjan Housmand Jane O’Reilly Angela Wolff Sauder School of Business University of British Columbia Under Review, Human Relations Journal 2 Escaping Bullying: The Simultaneous Impact of Individual and Unit-Level Bullying on Turnover Intentions In this study, we investigate the simultaneous impact of, and interaction between, being the direct target of bullying and working in an environment characterized by bullying upon employees’ turnover intentions. Hierarchical linear modeling analysis of a sample of 41 hospital units and 357 nurses demonstrates that working in an environment characterized by bullying increases individual employees’ turnover intentions. Importantly, employees report similarly high turnover intentions when they are either the direct target of bullying or when they work in work units characterized by high bullying. Results also suggest that the impact of unit-level bullying is stronger on those who are not often directly bullied themselves. 3 Organizational members can, and often do, interact with one another in harmful ways. Indeed, a primary source of adversity and distress at work emanates from interactions with other people (Basch & Fisher, 1998). Many streams of research have focused upon the prevalence and impact of socially harmful behaviors, such as aggression, interpersonal deviance, social undermining, incivility, interactional injustice, harassment, abusive supervision and workplace bullying. Although these streams address somewhat different subsets of behavior, they uncover a pattern: the experience of mistreatment at work is commonplace and it is detrimental to its targets (Ashforth, 1997; Berdahl & Raver, 2011; Bennett & Robinson, 2003; Duffy, Ganster, & Pagon, 2002; Hershcovis & Barling, 2010; Tepper, 2000). Being the target of mistreatment has been associated with a range of negative outcomes, but perhaps the most common is employees’ desires to escape from it. Decades of research have shown that employees report heightened withdrawal and turnover intentions when they experience mistreatment at work (e.g., Cortina, Magley, Williams & Langhout, 2001; Glomb, Richman, Hulin, Drasgow, Schneider & Fitzgerald, 1997; Hershcovis & Barling, 2010; LeBlanc & Kelloway, 2002; Lim, Cortina, & Magley, 2008; Miner-Rubino & Reed, 2010; Spence Laschinger, Leiter, Day & Gilin, 2009; Tepper, 2000). Although the impact of mistreatment on those who directly and personally experience such behavior is well-documented in the literature, much less is known about the effects of mistreatment at the level of one’s work environment. Can the mistreatment of others in the work environment affect individual employees, even when they are not the direct target of this mistreatment? And if so, what kind of effect does mistreatment in the work environment have on individual employees? To date, only a handful of studies have addressed these research questions. Some studies have looked at the effects of mistreatment in groups on individuals’ 4 propensity to engage in similar antisocial behaviors (e.g., Robinson & O’Leary-Kelly, 1998; Glomb & Liao, 2003) or the likelihood of being a target of these behaviors in workgroups with a either high or low prevalence of mistreatment (e.g., Duffy, Shaw, Scott, & Tepper, 2006). In this research, we explore the impact of workplace bullying in a work-unit on individuals’ turnover intentions. We seek to understand whether bullying in the work unit environment can have a negative impact on one’s desire to remain in their organization, independent of their personal or direct experiences of workplace bullying. Workplace bullying is the repeated exposure over time to mistreatment and acts of aggression by others within one’s organization, including from subordinates, supervisors and colleagues (Einarsen, Hoel & Notelaers, 2009, p. 24). We chose to look at workplace bullying rather than other forms of mistreatment because the subset of behaviors that capture bullying tend to be apparent to others, at least in comparison to other common forms of mistreatment. For example, bullying tends to be less insidious and subtle than the subset of behaviors that capture constructs such as incivility (Andersson & Pearson, 1999) and social undermining (Duffy et al., 2002). Even when bullying is not directly observed by or easily discernable to a bystander, its existence can easily spread through gossip and other means of social communication present in an organization’s social environment (Foster, 2004; Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978). Thus, similar to other scholars, we recognize that bullying does not occur in a social vacuum in the workplace (e.g., Duffy, et al., 2006; LePine & Van Dyne, 1998), and that certain features of a given work environment, such as bullying, are likely to be accessible to all members of a group or organization, even when they are not directly experienced or observed (Hackman, 1992). We argue that bullying at the work unit level is likely to have an impact on individual turnover intentions, independent of whether on is the target of bullying or not. Turnover 5 intentions may not necessarily lead to actual turnover, but a number of studies point to a very high correlation, especially in occupations where alternative employment options are readily available (Steel & Ovalle, 1984; Parasuraman, 1982). Furthermore, the costs of turnover for organizations are significant (Waldman, Kelly, Arora & Smith, 2004), and for those who intend to quit but cannot and remain silent about their bullying experience, the costs may be even higher to organizations (Milliken, Morrison & Hewlin, 2003). It is very important for us to consider not only the direct effects of bullying, but also the simultaneous and moderating effects of bullying in the work unit. This study highlights the cost of bullying that can extend beyond the direct target. We draw our theoretical arguments for the simultaneous and moderating impact of unit-level bullying on individual turnover intentions from the deontic model of justice and we characterized bullying as a violation of moral norms that can trigger deontic reactions (Folger, 1998; 2001; Folger, Cropanzano, & Goldman, 2005). The deontic model states that individuals can be concerned over unfair treatment, regardless of whether they are the direct target, because unjust treatment represents a moral violation of normative standards of how one should treat others (Folger, 1998; 2001; Folger, et al., 2005). Furthermore, we conceptualize turnover intentions and quitting one’s workplace as a deontic act characterized as a form of organizational resistance (Lawrence & Robinson, 2007; LutgnSandvik, 2005). Thus, before discussing our formal hypotheses, we first provide a summary of the deonance model of unfair treatment and present a conceptual link between the notion of deonance justice, workplace bullying and turnover intentions. The Deontic Perspective The deontic model situates justice concerns on the understanding of how one should and should not treat others. Folger (2001) coined the term deonance to refer to the psychological and 6 emotional-laden state that permeates from one’s reactions to actions perceived as violating significant moral standards. The deontic model of justice states that people can be motivated towards justice out of a sense of moral obligation, because “it is the right thing to do” (Folger, 2001), as an end in and of itself. Importantly, when others infringe upon moral standards it can provoke a reaction because of their apparent disrespect and ignorance of the implicit social rules that others have tried to uphold (Folger, 2001; Miller, 2001). Deontic reactions are characterized by an intense feeling of moral indignation, or anger towards the perpetrator of unfair treatment, and strong motivations to restore the moral order that has been infringed upon (Folger, 2001; Folger et al., 2005). The deonance perspective of organizational justice provides an explicit conceptual link between the concepts of justice and morality. Furthermore, unlike traditional models of unfair treatment that have generally focused upon the self-interested motivations that trigger reactions to unfair treatment, the deontic model explains why people can become upset and angered even when they are not directly treated unfairly. Folger and Skarlicki (2008) theorized that deontic judgments of right and wrong derive from evolved and adaptive psychological systems. In accordance with this view, Haidt and colleagues (Haidt & Graham, 2007; Haidt & Joseph, 2004) have narrowed the foundational values of moral reactions to five underlying sources: harm/care; fairness; loyalty; respect; and purity. When one’s actions violate a standard established upon one or more of these foundational criteria people can experience deontic reactions and be moved to react. The importance of each of these foundational criteria can vary across different cultures, however harm/care and fairness tend to be relatively more ubiquitous foundations than the other three (Haidt & Graham, 2007; Haidt & Joseph, 2004). O’Reilly and Aquino (2011) argue that individual differences capturing the extent to which individuals care about morality in general and are concerned about the 7 welfare of others can also influence the extent to which they experience deontic reactions when a perceived moral standard has been violated. The actions one takes to restore the moral order or “get even” with a perpetrator of injustice can be broad. On an interpersonal level, deontic reactions can sometimes take the form of revenge, or attempts to harm someone after they have committed a perceived wrongdoing (Bies & Tripp, 1998; Miller & Vidmar, 1981). People generally perceive revenge to be a moral endeavour when it is used to deter someone from engaging in further harmful behaviors. Another form of deontic response is resistance, defined as any active or passive act that attempts to disrupt or erode another social entity’s base of power (Lawrence & Robinson, 2007; LutgenSandvik, 2005, 2006). Importantly, some of the most common forms of organizational resistance are turnover intentions, psychological withdrawal and quitting (Lutgen- Sandvik, 2005, 2006). Revenge can often be a costly reaction that triggers further negative retributions. In contrast, resistance through passive withdrawal, not going beyond one’s formal work duties and quitting as soon as an opportunity for another job arises is discrete, does not break any explicit moral norms, and is less likely to trigger further retaliation. Thus, for example, employees will quit in protest of what they feel are unfair managerial procedures, policies and changes (e.g., Chalykoff & Kochan, 1989; Shapiro & Kirkman, 1999; Tucker, 1993). Pertinent to the current study, qualitative work by Lutgen-Sandvik (2005, 2006) on bullying victims has shown that quitting, including the desire to quit, is one of most prevalent forms of resistance in response to workplace bullying. In line with the deonance perspective, both the targets and witnesses of bullying can perceive resistance towards a bully, or an organization that fails to reprimand a bully, as a moral obligation (Lutgen- Sandvik, 2005). This work provides insight into the targets’ of bullying understanding of their experiences and 8 challenges the ‘passive’ view of workplace bullying which characterizes the targets of bullying as hapless victims who are too vulnerable and weak to fight their bullies. Instead, the targets of bullying see “escaping” their own and others’ bullies as a means to create turmoil and disrupt the organization in an act of defiance. Given that these sentiments are not based solely upon the consequences of bullying, but also the moral standards that bullying infringes upon, they are potentially available to all those involved in a bullying environment, including third parties. While this work provides evidence to suggest that at least some third parties will be moved by moral indignation to resist an organizational environment with significant bullying, we do not know whether such a trend will exist in work-units as a whole nor how individual experiences of bullying influences reactions to bullying within the broader environment. We explore this possibility to provide a further understanding of the unit-level costs of bullying. The Current Study In this research, we study the simultaneous and interactive effects of direct and unit-level bullying on turnover intentions in a sample of nurses. Workplace bullying is often a prevalent phenomenon in the health care industry and nurses tend to have a greater likelihood of experiencing such harmful behaviors than other healthcare professionals (e.g., Duffy, 1995; Hogh, Hoel, & Carneiro, 2011; Hutchinson, Vickers, Jackson, & Wilkes, 2006; Quine, 1999, 2001). Furthermore, bullying in the healthcare industry is associated with a host of negative jobrelated and health-related outcomes (e.g., Hogh et al., 2011; McVicar, 2003; Quine, 2001) As a starting point, we posit that employees who are subject to bullying will report higher turnover intentions, as is consistent with prior findings and theorizing. Adverse or dissatisfying elements of work, such as bullying from others, can trigger the withdrawal process, of which intentions to quit is the first step (e.g., Hulin, 1991; Hom & Griffeth, 1995; Mobley, 1977). 9 Research has shown that withdrawing from the organization can be an effective means by which to react to aversive work environments and avoid subsequent bad feelings (Brayfield & Crockett, 1955; Chadwick-Jones, Nicholson & Brown, 1982; Hackett & Guion, 1985). Hypothesis 1: Being the target of bullying is positively related to turnover intentions, independent of the extent of bullying in one’s work unit. We further argue that the degree of bullying in one’s work-unit at large will also be positively related to individual turnover intentions. Most importantly, the impact of unit-level bullying will be independent of, and in addition to, the actual bullying one receives from others. Thus, even when an employee is not bullied, she or he will desire to quit the organization to the extent that his or her work unit is characterized by bullying. Drawing from the deontic perspective, we argue that working in an environment in which others are bullied will create a sense of moral uneasiness that will contribute to their own turnover intentions, regardless of whether one personally experiences bullying. Workplace bullying can create a deontic state because it violates significant and entrenched moral norms of how others ought to treat one another, in ways that preserve dignity and respect (Bies & Moag, 1986). Furthermore, moral norms of treating others with a basic level of dignity and respect are often considered to be universal and applicable to all human beings, by virtue of a common humanity, even if some may infringe upon these norms (Nieman, 2008). Furthermore, the aggressive and painful acts that characterize workplace bullying are often considered to be volitional (Keashly, 1998; Lutgen-Sandvik, 2005; Neuman & Baron, 1998) and the extreme negative impact of workplace bullying is well-documented in the literature and thus 10 violates the moral standard of preventing harm towards others (Haidt & Graham, 2007; Haidt & Joseph, 2004). Witnessing or learning about these impacts of workplace bullying is likely to promote empathetic responses. Employees witnessing coworkers being bullied, or merely talking to them about their experiences, are pushed toward taking the targets’ perspective. Such perspective taking leads one to experience cognitive or emotional empathy, which includes imagining how another feels (Clark, 1980; Eisenberg, Fabes, Murph, Karbon, Maszk, Smith, O’Boyle & Suh, 1994) or actually sharing in another’s feelings (Hoffman, 1977). These empathetic responses can contribute to the understanding that a significant moral violation has occurred and the recognition that the victim does not deserve his or her mistreatment. As a result of this moral uneasiness, bullying at large within a work-unit will increase employee intentions to quit their work-group. Thus, we offer the following hypothesis. Hypothesis 2: Work unit-level bullying is positively related to turnover intentions, independent of the extent to which one is a direct target of bullying. The question then becomes, does work unit-level bullying have a similar impact on both those who experience a lot of workplace bullying directly as it does on those who experience comparatively less direct bullying? We hypothesize that the effect of work-unit level bullying on turnover intentions will be stronger to the extent that one is not bullied themselves. This is because the discrepancy between one’s relatively positive treatment by others, compared to others experience of bullying, evokes stronger deontic concerns. Witnessing others being bullied already evokes a sense of moral indignation, but the added discrepancy between one’s own good 11 treatment and others poor treatment, makes it seem even more unfair. Moreover, one's good treatment provides a model of comparison of how one's coworkers could and should have been treated (Folger & Cropanzano, 1998). This line of reasoning is supported by those who have found consistency to be a key criterion of justice (Leventhal, 1980; Rupp, Bashshur & Liao, 2007). It is also congruent with past studies showing that injustice directed toward an individual in a group impacts others in that group more when those others are not also experiencing injustice (Colquitt, Noe, & Jackson, 2002; Spencer, & Rupp, 2009). Thus we predict a stronger relationship between work unit-level bullying and turnover intentions for those who experience less bullying directly. Hypothesis 3: There is an interaction effect between direct bullying and work unit-level bulling such that the relationship between work unit-level bullying and turnover intentions is stronger for individuals who experience less direct individual-level bullying, compared to those who experience more. Methods Data and Sample The data used for this study was collected from nurses in 41 units of a large health authority in a western Canadian city. We administrated two surveys, two months apart, to 1385 nurses. Survey participation was voluntarily and confidential. For the first survey, we received 567 responses, of which 519 were valid in terms of survey completion (response rate = 41%). In the second survey, we received 422 responses, of which 398 had met our requirements to be included for this study (response rate = 30%). After 12 merging both surveys, based on our sampling criteria, our final sample included 357 participants, with an average age of 43 years (SD = 11.6 years), and with an average tenure of 16 years (SD = 12 years). The average unit size was 31 (SD = 6.8) and the average number of survey respondents per unit was 9 (SD =3). Measures Individual-Level Bullying We measured the extent to which one directly experienced bullying using 17 items based on the Aggressive Experience Scale (Glomb & Liao, 2003). This is a validated instrument that assesses individuals’ perceptions of the extent to which they are bullied by their coworkers. This measure covers a wide diversity of harmful interpersonal behaviours at work, ranging from relatively minor bullying behaviors, to more extreme behaviours. Respondents were asked, “How often have you experienced the following situations or behaviors from your nursing colleagues that work in this nursing unit in the past 6 months”, using a 7-pt Likert scale ranging from “never” to “always,”. Example items included, “made angry gestures at you (e.g. pounding fist, rolling eyes),” “withheld resources (e.g. supplies equipment) needed to do your job,” “physically assaulted you” and “damaged your property.” We collected participants’ reports of bullying behavior in the first survey. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .90. Work Unit-level Bullying. We measured work unit-level bullying by averaging across the individual-level, or direct, reports of employees within each work unit using hierarchical linear modeling software. We averaged individuals’ direct reports of their own experiences because even when specific acts of bullying are not directly observed by others within a particular workgroup, bullying is likely to be an ambient work-unit element and the negative emotions 13 associated with it can happen without a particular employee’s direct knowledge. We therefore used an additive composition model. In additive composition models, a higher level construct is composed of lower level constructs regardless of the variance among the lower constructs (Chan, 1998). This method is consistent with Glick’s (1985) conceptualization of constructing organizational climate from a psychological climate. It is important to note that although the work unit-level bullying includes the focal individual’s report of bullying, the focal individual’s report comprises, on average, only 3% of the work unit (given an average work unit size of 31); moreover, with the use of hierarchical linear modeling, we are able to report the unique variance explained in work unit-level bullying over and above that accounted for by the focal individual’s report of direct experience of bullying. Turnover Intentions We used Chatman’s (1991) seven item measure to capture turnover intentions. We measured turnover intentions on both surveys. Example items include, “If I had a chance, I would change to some other organization,” and “I often think about resigning.” Respondents used a 5-pt Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. The Cronbach’s alphas were .78 and .80 for turnover at time 1 and time 2 respectively. Control Variables. Along with controlling for turnover intentions at time 1, we also controlled for a number of other variables that could potentially predict turnover intentions at time 2. First, we controlled for several demographic variables age and tenure, that have been shown to be significant related to turnover intentions, especially in recent studies examining turnover among nurses (e.g. Delobelle, Rawlinson, Ntulis, Malatsi, Decock & Depoorter, 2011; De Gieter, S, Hofmans, J & Pepermans, R., 2011; Gray & Phillips, 1994; Haifer, 2011; Mobley, Horner, & Hollingsworth, 1978)). 14 We also controlled for a particularly relevant contextual variable- unit size- because it has been repeatedly shown to be related to turnover and turnover intentions in numerous recent nursing studies (Blegen, M, Vaughn, T., & Vojir, C. 2008; Sellgren, Kajermo, Ekvall, G. & Tomson, G., 2009) and it serves as a proxy for many contextual challenges facing nursing staff. Finally, we also include a social support measure as it is conceivable that being bullied and working in an environment of bullying may reflect the absence of social support, which is a primary buffer against stress and identified as such a critical predictor of turnover intentions, especially among healthcare providers (see Barak, Nissly, Levin, 2001 and Tai & Bame, 1998, for reviews). Using a roster method, we provided each respondent with the employee list of the unit to which the respondent belonged. Next, the respondents were asked to identify the colleagues who had provided them social support in the past six months. The social support measure was calculated based on the number of employees identified by the respondents divided by the unit size. At the unit-level, we controlled for the unit size which assessed the total number of nurses working in a unit (Bliese, 1998). We also controlled for turnover intentions at time 1 as well. Analysis We used hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) to analyze our data. We chose HLM because it enables us to examine the simultaneous effects of variables at different levels of analysis within the same model (Hofmann, 1997); in this case, control variables, bullying, and turnover intentions at the individual level, and at the group level, socially toxic environment and unit size. Before conducting our HLM analysis, we assessed the variability of the individual’s turnover intentions within and between groups. We used the between groups and within group 15 variance estimates provided by HLM analysis to calculate how much the variance of individuals’ turnover intentions are accounted for by variance in the group level (Hofmann, 1997). We performed one-way ANOVA in HLM and measured the intra-class coefficients (ICC), which measures the extent to which the variation in the dependent variable is explained by the next level (Hox, 2002). We observed that there was a significance difference between groups (τ00 = .11, χ2(40)= 84.38, p < .01). The ICC for the turnover intentions at time 2 was .27. The value of ICC suggested that variations in hospital units accounted for 27% of the variability of nurses’ turnover intentions at time 2. This analysis, combined with the nested structure of our variables, provides valid support to use HLM to analyze our data. Further, we standardized our variables for ease of interpretation and to reduce potential multi-collinearity (Hofmann & Gavin, 1998). Results Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics among the dependent, independent and control variables measured at both the individual and unit- levels. _____________________ INSERT TABLE 1 ABOUT HERE _____________________ Hierarchical linear modeling is a statistical technique that simultaneously takes into account the effect of variables from different levels of analysis. In this case, tests of hypotheses 1 and 2 include the combination of two regression models at the individual level and unit level. Level 1 (individual level): 16 (1) Level 2 (unit level): (2) Therefore, the predicted equation becomes (3) Table 2 presents the results of our hierarchical linear modeling analysis. The main effects of individual-level bullying and work unit-level bullying are shown in Model 2. Hypothesis 1 predicted that being the target of bullying is positively related to individuals’ turnover intentions. The prediction is consistent with the significant coefficient for being the target of bullying (β = .08, p < .05). Thus, Hypothesis 1 is supported. _____________________ INSERT TABLE 2 ABOUT HERE _____________________ Hypothesis 2 predicted that work unit-level bullying would have a positive relationship with turnover intentions, whilst controlling for direct experiences of bullying. The coefficient for work unit-level bullying is significant (β = .07, p < .05). Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported. Hypothesis 3 predicted that there is an interaction between individual- and work unitlevel bullying, such that positive relationship between work unit-level bullying and turnover 17 intentions is stronger for those who experience less direct bullying, compared to those who experience more. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a cross-level moderator analysis in HLM (e.g., Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, & Congdon, 2004). Model 3 shows a significant coefficient for the interaction term (β = -.06, p < .10). This interaction is graphically depicted in Figure 1. As predicted, the positive relationship between work unit-level bullying and turnover intentions is stronger for those who infrequently experience direct bullying (-1SD), compared to those who are bullied often (+1SD), supporting Hypothesis 3. The graph also indicates that the cumulative impact of bullying is strongest for those who are bullied often and work in a work unit characterized by high bullying. ______________________ INSERT FIGURE 1 ABOUT HERE ______________________ Discussion How does bullying influence turnover intentions? Consistent with past studies, the results of this study show that when people are bullied at work, they have a stronger desire to leave their organization (Hauge, Skogstad & Einarsen, 2010; McKay, Arnold, Fratzl & Thomas, 2008). Given that bullying is most often a painful and distressing experience, it is not surprising that people want to avoid situations in which they must endure uncivil, harassing or aggressive behaviors from others in their workplace environment. Such sentiments can often lead to employees actually leaving their organizations when an opportunity arises. Even when employees are unable to quit their jobs and leave their organization when they face a high degree of being bullied, simply thinking about leaving may help them cope with and resist this negative treatment. 18 Importantly, the results of this study show that people are not only aversively affected by their own experience of being bullied, but that the bullying experience of others in their work units can have significant effects as well. Our results show that merely working in a work unit with a considerable amount of bullying is linked to higher employee turnover intentions. This is consistent with prior studies that have revealed the impact of environmental level effects of specific harmful behaviors such as sexual harassment or incivility (Glomb et al 1997; Lim & Cortina, 2008). Our findings add to these findings, however, in two ways. First, we examined a broad, varied and generalized experience of bullying. Second, because we relied on hierarchical linear modelling techniques, we were able to accurately examine the simultaneous impacts of direct bullying and ambient bullying, showing each unique effect above and beyond that accounted for by the other (something not possible with earlier statistical techniques). Of particular note is the fact that we could predict turnover intentions as effectively by either how much one was the target of bullying, or by how much one’s work environment was characterized by bullying. This is potentially interesting because we tend to assume that direct, personal experiences should be more influential upon employees than indirect experiences only witnessed or heard about in a second hand fashion. Yet our study identifies a case where direct and indirect experiences have a similarly strong relationship to turnover intentions. These findings point to the potential importance of a growing area of research in organizational behaviour that gives attention to and addresses third party experiences. To date, most of our research has focused upon the direct experiences of actors or targets in interpersonal organizational dynamics, and we are only beginning to understand the significance of being a third party to those dynamics. 19 Drawing from recent developments on deontic justice, we suggest that simply working in an aggressive environment can lead to turnover intentions because bullying represents a severe moral transgression that creates an abstract sense of moral uneasiness. As a result of this deonance state, third parties, or those who are not the direct target of bullying, can be moved to quit their organization as soon as an opportunity arises out of disgust and protest towards the bullies and towards their organization, which does not prevent the bullying or reprimand the bullies. Although the correlational nature of our study prohibits us from drawing such bold conclusions, we encourage future research to establish a stronger cause and effect relationship than our study permitted, as well as attempt to capture the particular mechanisms or pathways by which employees are impacted by ambient bullying. Finally, in this study we were able to demonstrate that the relationship between being work unit-level bulling and intentions to quit was dependent, in part, upon whether one is directly targeted. When someone is bullied directly, the impact of bullying within the work unit is weaker than when one is not the direct target of bullying. This finding recognizes the fact that we are often more concerned about our own mistreatment than the mistreatment of others when we are dealing with our own tribulations and suffering. However, even those who are directly targeted by bullying are at least somewhat moved by the bullying of others. Our findings suggest some potential insights about the role of context (Johns, 2006) in understanding bullying. We thus contribute to the general stream of meso-level research by highlighting how the bullying context can influence individuals’ reactions (Klein, Tosi, & Cannella, 1999; Mathieu & Chen, 2011). We also have hopefully added to the new but quickly growing literature on the third parties in organizational environments who may be, as our study suggests, as impacted by organizational dynamics and exchanges as much or even more so as 20 those who are directly targeted. Our future studies not only need to continue to incorporate an simultaneous examination of effects at different levels of the organization by routinely using hierarchical linear modelling, but these results suggest we also need empirical research to determine the actual mediating mechanisms that can explain the higher level or environmental effects. Limitations and Future Directions Our research design did not enable us to determine the direction of causality between our variables. However, we contend that the most theoretically parsimonious explanation for our main effects is that bullying, especially at the work-unit level, drives one’s turnover intentions rather than one’s turnover intentions drive one’s experience of being bullied or the degree of bullying on one’s work environment. Likewise, it is difficult to imagine how our moderation effect- that the impact of work-unit level bullying upon turnover intentions is greater for those who infrequently experience bullying that for those who do not- operates in a different causal direction than that which we propose. Nevertheless, future studies involving multiple waves of data collection will ultimately provide stronger evidence of causal relationships between bullying, work-unit level bullying, and turnover intentions. Another limitation we would like to note is that our study measures turnover intention, not behaviour. Although prior research finds turnover intentions and behaviour to be moderated related (Steel & Ovalle, 1984), this relationship may be much stronger in occupations such as nursing have strong labor markets. Moreover, we content that predicting turnover intentions itself is worthwhile because organizations are also harmed by having employees with turnover 21 intentions but who stay on. Nevertheless, we believe that future studies, which can examine both intended and actual turnover over time would be worthwhile. Managerial Implications Our findings may offer some practical implications for hospitals and health care organizations. They suggest that organizations need to be mindful of mistreatment incidents for two reasons. First, our findings are consistent with prior research that suggests that the targets of bullying develop undesirable organizational attitudes and/or behaviours e.g. increased turnover intention. Perhaps more importantly though, our findings allude to the possibility that socially toxic environments can emerge out of individual incidents of bullying, spreading negative attitudes and behaviours throughout a group. While the loss of individual employees may be absorbed by organizations, a potential mushrooming effect in socially toxic environments presents a greater need for management to take protective action against mistreatment among employees. Conclusion In this study we demonstrate the simultaneous and interactive effects of being the target of bullying and merely working in an environment characterized by bullying upon turnover intentions. Our findings suggest the importance of future research on examining the multi-level effects of bullying, but also suggest the importance of examining ambient bullying and the mechanisms through which it influences turnover intentions and a host of other organizationally relevant outcomes. 22 TABLE 1 Correlations and Descriptive Statisticsa ` Mean S.D. 1. Age 43.4 11.58 2. Tenure 16.36 12.17 0.83** 3. Unit Size 30.68 6.75 -0.14* -0.07 4. Social Support 0.39 0.25 0.025 -0.02 -0.05 5. Turnover Intentions at T1 2.32 0.79 -0.26** -0.27** 0.1 -0.13* 6. Individual Bullying 7. Unit-Level Bullying 8. Turnover Intentions at T2 1.29 1.29 2.36 0.38 0.15 0.79 -0.14** -0.05 -0.35** -0.1 -0.04 -0.29** -0.1 -0.22** 0.09 -0.06 -0.02 -0.08 a 1 N=357 participants in 41 units. Notes: * p<.05 (two-tailed); ** p<.01 (two-tailed) 2 3 4 5 0.32** 0.14** 0.77** 6 0.41** 0.35** 7 0.21** 23 TABLE 2 HLM Results for Effects of Individual-Level Bullying and Unit-Level Bullying on Turnover Intentions Turnover Intentions at Time 2 Variables Model 1 Unit size Model 2 Model 3 .02 .02 Tenure .09 .09* .09* Age -.22*** -.23*** -.22*** Turnover Intentions (Time 1) .70 *** .70*** .69*** Social Support .03 .03 .03 Individual-Level Bullying .11** .08** .13** .07* .08* Unit-Level Bullying Interaction -.06 * Individual Bullying X Unit-Level Bullying R-squared a 0.64 For ease of interpretation, we report standardized coefficients. N=357 participants in 41 units. Note: * p<.05 (one-tailed); ** p<.01 (one-tailed); *** p <.001(one-tailed) 24 FIGURE 1 The Impact of Unit-Level Bullying on Turnover Intentions in High versus Low Levels of Individual Bullying Low Levels of Individual Bullying High Levels of Individual Bullying Low High 25 REFERENCES Andersson LM and Pearson CM (1999) Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Academy of Management 24: 452-471. Ashforth BE (1994) Petty tyranny in organizations: A preliminary examination of antecedents and consequences. Human Relations, 47, 755-778. Barak M, Nissly JA and Levin A (2001) Antecedents to retention and turnover among child welfare, social work, and other human service employees: What can we learn from past research? A review and meta-analysis. Social Services Review 74: 625. Basch J and Fisher CD (1998) Affective events—Emotions matrix: A classification of work events and associated emotions. Paper presented at the First Conference on Emotions in Organizational Life, San Diego. Bennett RJ, Robinson SL (2003) The past, present, and future of workplace deviance research. In Greenberg J (ed) Organizational behavior: The state of the science (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. Berdahl JL, Raver JL (2011) Sexual harassment. In Zedeck S (ed) APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology 3: Maintaining, expanding, and contracting the organization. Washington, DC US: APA. Bies RJ and Moag J (1986) Interactional justice: Communication criteria of fairness. In Lewicki R, Sheppard B and Bazerman M (eds) Research on negotiation in organizations. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 43-55. Bies RJ and Tripp TM (1998) Revenge in organizations: The good, the bad and the ugly. In Griffin RW, O’Leary-Kelly A and Collins J (eds) Monographs in organizational behavior and industrial relations. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Blegen M, Vaughn, T and Vojir C (2008) Nurse staffing levels: impact of organizational characteristics and registered nurse supply. Health Services Research 43: 154-173. Bliese PD (1998) Group size, ICC values, and group-level correlations: A simulation. Organizational Research Methods 1(4): 355-373. Brayfield AH, Crockett WH (1955) Employee attitudes and employee performance. Psychological Bulletin 52(5): 396-424. Chadwick-Jones JK, Nicholson N and Brown CA (1982) Social psychology of absenteeism. New York: Praeger Publishers. Chalykoff J and Kochan TA (1989) Computer-aided monitoring: Its influence on employee job satisfaction and turnover. Personal Psychology 807-834. 26 Chan D (1998) Functional relations among constructs in the same content domain at different levels of analysis: A typology of composition models. Journal of Applied Psychology 83(2): 234-246. Chatman JA (1991) Matching people and organizations: Selection and socialization in Public Accounting Firms. Administrative Science Quarterly 36(3): 459-484. Clark KB (1980) Empathy: A neglected topic in psychological research. American Psychologist 35(2): 187-190. Colquitt, J A, Noe, RA, and Jackson, CL (2002). Justice in teams: Antecedents and consequences of procedural justice climate. Personnel Psychology 55: 83–109. Cortina LM, Magley VJ, Williams J and Langhout R (2001) Incivility in the workplace: Incidence and impact. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 6(1): 64-80. Delobelle P, Rawlinson JL, Ntuli S, Malatsi I, Decock R and Depoorter AM (2011) Job satisfaction and turnover intent of primary healthcare nurses in rural South Africa: a questionnaire survey. Journal of Advanced Nursing 67(2): 371–383. De Gieter S, Hofmans J and Pepermans R (2011) Revising the impact of job satisfaction and commitment on nurse turnover intentions: An individual differences analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies 48: 1562-1569. Duffy E (1995) Horizontal violence: A conundrum for nursing. Collegian 2: 5–17. Duffy MK, Ganster DC and Pagon M (2002) Social undermining in the workplace. Academy of Management Journal 45: 331-352. Duffy MK, Shaw JD, Scott KL and Tepper BJ (2006) The moderating roles of self-esteem and neuroticism in the relationship between group and individual undermining behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology 91: 1066-1077. Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Murphy B, Karbon M, Maszk P, Smith M, O’Boyle C and Suh K (1994) The relations of emotionality and regulation to dispositional and situational empathyrelated responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 66(4): 776-797. Einarsen S, Hoel H and Notelaers G (2009) Measuring exposure to bullying and harassment at work: Validity, factor structure and psychometric properties of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised. Work & Stress 23(1): 24-44. Folger R (1998) Fairness as a moral virtue. In Schminke M (ed), Managerial ethics: Moral management of people and processes. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1334. 27 Folger R (2001) Fairness as deonance. In Gilliland SW, Steiner DD and Skarlicki DP (eds), Theoretical and cultural perspectives on organizational justice. Greenwich, CT: IAP, 333. Folger, R and Cropanzano, R (1998). Organizational justice and human resource management. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Folger R, Cropanzano R and Goldman B (2005) What is the relationship between justice and morality? In Greenberg J and Colquitt JA (eds) Handbook of organizational justice. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 215-245. Folger R and Skarlicki DP (2008) The evolutionary basis of deontic justice. In Gilliland S, Steiner D and Skarlicki D (eds) Research in social issues in management: Justice, morality, and social responsibility. Greenwich CT: Information Age Publishing, 29-62. Foster E K (2004) Research on gossip: Taxonomy, methods and future directions. Review of General Psychology 8: 78-99. Glick WH (1985) Conceptualizing and measuring organizational and psychological climate: Pitfalls in multilevel research. Academy of Management Review 10: 601–616. Glomb TM and Liao H (2003) Interpersonal aggression in work groups: Social influence, reciprocal, and individual effects. Academy of Management Journal 46: 486-496. Glomb TM, Richman WL, Hulin CL, Drasgow F, Schneider KT and Fitzgerald LF (1997) Ambient sexual harassment: An integrated model of antecedents and consequences. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 71(3): 309-328. Gray AM and Phillips VL (1994) Turnover, age and length of service: a comparison of nurses and other staff in the National Health Service. Journal of Advanced Nursing 19(4): 819827. Hackett RD and Guion RM (1985) A reevaluation of the absenteeism-job satisfaction relationship. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 35(3): 340-381. Hackman JR (1992) Group influences on individuals. In Dunnette MD (ed) Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Haidt J and Graham J (2007) When morality opposes justice: Conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Social Justice Research 20: 98-116. Haidt J and Joseph C (2004) Intuitive Ethics: How Innately Prepared Intuitions Generate Culturally Variable Virtues. Daedalus Fall: 55-66. 28 Haifer D (2011) Job embeddedness Factors and Retention of Nurses With 1 to 3 years of experience. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing 42: 468-476. Hauge L, Skogstad A and Einarsen S (2010) The relative impact of workplace bullying as a social stressor at work. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 51(5): 426-433. Hershcovis M and Barling J (2010) Towards a multi-foci approach to workplace aggression: A meta-analytic review of outcomes from different perpetrators. Journal of Organizational Behavior 31(1): 24-44. Hogh A, Hoel H and Carneiro IG (2011) Bullying and employee turnover among healthcare workers: a three-wave prospective study. Journal of Nursing Management 19: 742-751. Hofmann DA (1997) An overview of the logic and rationale of hierarchical linear models. Journal of Management 23(6): 723-744. Hofmann DA and Gavin MB (1998) Centering decisions in hierarchical linear models: Implications for research in organizations. Journal of Management 24(5): 623-641. Hom PW and Griffeth RW (1995) Employee turnover. Cincinnati: South-Western. Hox J (2002) Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Hulin C (1991) Adaptation, persistence, and commitment in organizations. In Dunnette MD and Hough LM (eds) Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, 2. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Hutchinson M, Vickers M, Jackson D and Wilkes L (2006) Workplace bullying in nursing: Towards a more critical organisationl perspective. Nursing Inquiry 13: 118-126. Johns G (2006) The essential impact of context on organiztional behavior. Academy of Management Review 31(2): 386-408. Keashly L (1998). Emotional abuse in the workplace: conceptual and empirical issues. Journal of Emotional Abuse 1(1): 85-117. Klein KJ, Tosi H and Cannella AA (1999) Multilevel theory building: Benefits, barriers, and new developments. Academy of Management Review 24(2): 243-248. Lawrence TB and Robinson SL (2007). Ain't Misbehavin: Workplace Deviance as Organizational Resistance. Journal of Management 33(3): 378-394. LeBlanc M and Kelloway E (2002) Predictors and outcomes of workplace violence and aggression. Journal of Applied Psychology 87(3): 444-453. 29 LePine JA and Van Dyne L (1998) Predicting voice behavior in work groups. Journal of Applied Psychology 83: 853–868. Leventhal, GS (1980). What should be done about equity theory? In K. J.Gergen, M. S.Greenberg, & R. H.Willis (Eds.), Social exchange: Advances in theory and research. New York: Plenum, 27-55. Lim S, Cortina LM and Magley VJ (2008) Personal and workgroup incivility: Impact on work and health outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology 93(1): 95-107. Lutgen-Sandvik P (2005) Water smoothing stones: Subordinate resistance to workplace bullying. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona. Lutgen-Sandvik, P (2006) Take this job and…: Quitting and other forms of resistance to workaplce bullying. Communication Monographs 73: 406-433. Mathieu JE and Chen G (2011) The etiology of the multilevel paradigm in management research. Journal of Management 37(2): 610-641. McKay R, Arnold D, Fratzl J and Thomas R (2008) Workplace bullying in academia: A Canadian study. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal 20(2): 77-100. McVicar A (2003) Workplace stress in nursing: A literature review. Integrative Literature Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Journal of Advanced Nursing 44(6): 633-642. Miller DT (2001) Disrespect and the experience of injustice. Annual Review of Psychology 52(1): 527. Miller DT and Vidmar N (1981) The social psychology of punishment reactions. In Lerner MJ and Lerner SC (eds) The justice motive in social behavior: Adapting to time of scarcity and change). New York: Plenum Press, 145-172. Milliken FJ, Morrison EW and Hewlin PF (2003) An exploratory study of employee silence: Issues that employees don’t communicate upward and why. Journal of Management Studies 40(6): 1453-1476. Miner-Rubino K and Reed WD (2010) Testing a moderated mediational model of workgroup incivility: The roles of organizational trust and group regard. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 40(12): 3148-3168. Mobley WH (1977) Intermediate linkages in the relationship between job satisfaction and employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology 62: 237-240. Mobley WH, Horner SO and Hollingsworth AT (1978) An evaluation of precursors of hospital employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology 63(4): 408-414. 30 Neiman S (2008) Moral clarity: A guide for grown-up idealists. New York: Harcourt. Neuman JH and Baron RA (1998) Workplace Violence and Workplace Aggression: Evidence Concerning Specific Forms, Potential Causes, and Preferred Targets. Journal of Management 24(3): 391-419. O'Reilly J and Aquino K (2011) A Model of Third Parties' Morally Motivated Responses to Mistreatment in Organizations. Academy of Management Review 36(3): 526-543. Parasuraman S (1982) Predicting turnover intentions and turnover behavior: A multivariate analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior 21(1): 111-121. Quine L (1999) Workplace bullying in NHS community trust: Staff questionnaire survey. British Medical Journal 318: 228–232. Quine, L. 2001. Workplace bullying in nurses. Journal of Health Psychology, 6, 73-84. Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Cheong YF and Congdon R (2004) HLM6: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International. Robinson SL and O’Leary-Kelly AM (1998) Monkey see, monkey do: The influence of work groups on the antisocial behavior of employees. Academy of Management Journal 41: 658-672. Rupp, DE, Bashshur, MR and Liao, H (2007). Justice climate past, present, and future: Models of structure and emergence. In F.Dansereau & F.Yammarino (Eds.), Research in multilevel issues (Vol. 6, pp. 357–396). Oxford, England: Elsevier. Salancik GR and Pfeffer J (1978) A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative Science Quarterly 23: 224-253. Sellgren SF, Kajermo KN, Ekvall G and Tomson G (2009) Nursing staff turnover at a Swedish university hospital: An exploratory study. Journal of Clinical Nursing 18: 3181-3189. Shapiro DL and Kirkman BL (1999) Employees’ reaction to the change to work teams: The influence of “anticipatory” injustice. Journal of Organizational Change Management 12(1): 51-66. Spence Laschinger HK, Leiter M, Day A and Gilin D (2009) Workplace empowerment, incivility, and burnout: impact on staff nurse recruitment and retention outcomes. Journal of Nursing Management 17(3): 302-311. Spencer, S and Rupp, D 2009. Angry, guilty, and conflicted: Injustice toward coworkers heightens emotional labor through cognitive and emotional mechanisms. Journal of Applied Psychology 94: 429-444. 31 Steel RP and Ovalle NK (1984) A review and meta-analysis of research on the relationship between behavioral intentions and employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology 69(4): 673-686. Tepper BJ (2000) Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal 43(2): 178-190. Tucker J (1993) Everyday forms of employee resistance. Sociological Forum 8: 25–45. Wai Chi Tai T and Bame S (1998) Review of nursing turnover research, 1977-1996. Social Science and Medicine 1905-1927. Waldman JD, Kelly F, Arora S and Smith HL (2004) The shocking cost of turnover in health care. Health Care Management Review 29(1): 2-7.